Disclaimer: This Jupyter Notebook contains content generated with the assistance of AI. While every effort has been made to review and validate the outputs, users should independently verify critical information before relying on it. The SELENE notebook repository is constantly evolving. We recommend downloading or pulling the latest version of this notebook from Github.

Language Models¶

In natural language processing (NLP), a language model is a core concept that enables machines to understand, generate, and predict human language. A language model assigns probabilities to sequences of words, helping systems determine how likely a sentence or phrase is in a given context. This ability allows language models to perform essential tasks such as text generation, machine translation, speech recognition, sentiment analysis, and more. By learning from large text corpora, these models can capture the structure and meaning of human language with increasing sophistication.

The development of language models has evolved significantly over time. Early models, such as n-gram models, relied on simple statistical methods that used fixed-length word sequences to predict the next word. These models were limited by their inability to understand long-range dependencies in language. The introduction of neural networks in the early 2010s marked a major turning point. Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) and later Long Short-Term Memory networks (LSTMs) allowed models to remember previous context better. However, the most significant leap came with the introduction of Transformer-based models like BERT, GPT, and their successors, which enabled parallel processing of text and a deeper understanding of context and semantics.

Understanding the concept and history of language models is essential for anyone exploring NLP or artificial intelligence. These models serve as the foundation for many modern applications, such as virtual assistants, chatbots, search engines, and automated writing tools. By understanding how language models have evolved—from rule-based systems to today’s deep learning models — practitioners can better appreciate their capabilities, limitations, and potential for future development.

Moreover, studying language models also helps us engage with broader issues such as AI bias, ethical language generation, and the societal impact of machine-produced content. As these models become more powerful and widespread, it becomes increasingly important to understand how they work and how they shape the way we communicate with technology. Thus, learning about language models is not just a technical pursuit, but a necessary step toward building responsible and effective AI systems.

Setting up the Notebook¶

Preliminaries¶

Parts of this notebook assume some basic knowledge about Recurrent Neural Networks and the Transformers — two common neural architectures to build and train language models. While not required to understand the underlying goals and ideas of language models, a basic knowledge helps to appreciate the difference between the various models.

To make all visualizations, examples, and descriptions easier to understand, we assume that any input text is tokenized into proper words. Note that practical language models — particularly RNN-based and Transformer-based models — typically rely on subword-based tokenizers (e.g., Byte-Pair Encoding, WordPiece).

With these clarifications out of the way, let's get started...

Motivation¶

For humans, understanding and using language feels natural because we start learning it from a very young age through constant interaction with people around us. We do not just learn words and grammar — we also learn tone, emotion, body language, and context, all of which help us figure out what others mean, even if they do not say things perfectly. Over time, our brains get very good at picking up patterns and filling in gaps, so we can understand things quickly, even when the language is unclear or informal.

Machines, on the other hand, do not learn language the way humans do. They need to be trained on huge amounts of text or speech data, and even then, they do not (yet) truly "understand" meaning — they just recognize patterns. Machines struggle with things like sarcasm, jokes, slang, or sentences that depend on background knowledge or context. Because language is so flexible and full of subtle cues, teaching a machine to handle it the way humans do is extremely difficult and still an ongoing challenge in artificial intelligence.

Let's first look at some example applications to better understand the challenges involved when solving tasks that require the understanding and generation of (written) language. These challenges then motivate the underlying idea of language models.

Example Applications¶

Spelling & Grammar Checking¶

Writing with proper spelling and grammar is important because it makes your message clear and easy to understand for the reader. It also reflects attention to detail and professionalism, which can impact how others perceive your credibility. Poor spelling or grammar can lead to confusion or misinterpretation of your ideas.

While spelling and grammar mistakes may show a poor command of a language, even people who mastered a language are often prone to make such mistakes. This is particularly true when typing text. In a rush, our fingers might slip and press the wrong key (including when using new and unfamiliar input devices), or we might simply fail to notice mistakes due to fatigue or distraction.

Spelling and grammar checking can be separated into two main task, the detection of mistakes and the correction of mistakes. While detecting is generally easier than correcting a mistake, both are often non-trivial tasks in practice. Consider, for example the following sentence containing two misspellings (marked in red):

"The dessert spans thousands of acress."

While both misspellings are caused by having typed an additional "s" character, even just their just detection pose different challenges. On the hand, detecting the misspelled word "acress" is relatively straightforward since it is not a (common) word in the English vocabulary. On the other hand, "dessert" is a common English word, but arguably not the correct one in the context of this sentence — it is still uncertain as the writer might describe a dream about large amounts of sweet food.

Trying to correct a misspelling is typically even more challenging. For example, given the misspelled word "acress", there a several ways to convert into a common English word by just editing single letter:

- "acres" (remove one "s")

- "across" (replace "e" with "o")

- "access" (replace "r" with "c")

- "actress" (insert "t")

- "caress" (transpose "ac" with ca — typically considered a single-error typo)

In such cases, we need some kind of ranking to tell which of these alternatives is more likely. Overall, spelling and grammar checking requires some mechanism to quantify if a word, phrase, or sentence is more likely than an alternative. For our example sentence, we would like I way to express that

"The desert spans thousands of acres." $>$ "The dessert spans thousands of acress."

where "$>$" means "more likely" or "is better".

Machine Translation¶

Machine translation is a challenging task primarily because of the complexity and variability of human language. Languages differ in grammar, syntax, word order, idiomatic expressions, and cultural context. Many words have multiple meanings depending on context, and selecting the correct one requires a deep understanding of the situation, tone, and intent. Another major challenge is preserving nuance, tone, and style in translation. Human translators consider not just literal meanings but also emotional undertones, cultural references, and rhetorical devices. Machines, on the other hand, rely on patterns in data and often fail to capture these subtleties, especially in literature, humor, or informal speech.

A good example is the short German sentence "Ich habe Hunger." which can be can be translated into English in several correct ways:

- "I have hunger. — a literal translation that's grammatically correct but sounds awkward or unnatural to native English speakers

- "I am hungry." — the natural and idiomatic English equivalent

- "I feel hungry." — also correct, though slightly different in tone or emphasis

All three convey the same basic meaning, but only the second sounds natural in everyday English. This illustrates how direct, word-for-word translations often miss the idiomatic or culturally appropriate expression, which is a common challenge in translation. In other words, some translations are less preferred than others even if they are strictly speaking — in the grammatical sense — not wrong. This again calls for some mechanism that allows the ranking of different translations, e.g.:

"I am hungry." $>$ "I have hunger.

"I feel hungry." $>$ "I have hunger.

"I am hungry." $\geq$ "I feel hunger.

where "$>$" may now mean "is preferred", "is better", or "is more common".

Speech Recognition¶

Speech recognition is a highly non-trivial task since spoken language is highly variable and context-dependent. People have different accents, speaking speeds, intonations, and pronunciation styles, which can make it difficult for systems to consistently interpret audio input. Background noise, overlapping speech, and unclear articulation can further complicate recognition. Additionally, spoken language often includes informal expressions, filler words, and fragmented sentences that don’t follow standard grammar rules.

Another major difficulty lies in understanding context and meaning. Many words sound alike (homophones) but have different meanings, and identifying the correct word often depends on the context of the conversation. For example, distinguishing between "there", "their", and "they're" in spoken language requires understanding the broader sentence structure and intent. Furthermore, recognizing named entities (like people's names or places) and adapting to domain-specific vocabulary (such as medical or legal terms) adds another layer of complexity to building accurate and reliable speech recognition systems. For example, consider the following sentence

"I ate cereal last night."

Although seemingly a very simple sentence, notice that it contains two homophones: "cereal" vs. "serial", and "night" vs. "knight". If we as humans hear this sentence, we generally have no problem identifying which words are meant as they are the only ones that make sense to us. However, the notion of "makes sense" is obvious how to implement. Thus, in case of homophones — but generally for all kinds of ambiguous cases — a speech recognition system has to identify the most likely choice of words. Once again, we need some mechanism that tells us that

"I ate cereal last night." $>$ "I ate serial last knight."

at least most of the time, acknowledging the possibilities of exceptions.

The Challenges of Modeling Natural Language¶

The three example applications illustrate the fundamental challenges when working with natural language — particularly with the goal of modeling natural language. These challenges directly derive from the common characteristics of natural language, which in turn directly affects any approaches to model it

Characteristics of Natural Language¶

In a nutshell, natural language is our way of communicating thoughts, feelings, opinions, ideas, etc. However, compared to formal languages like programming languages, all natural languages have not been a-priori defined but have been invented and evolved over time — and continue to evolve! — hence the notion of natural language. Although not formal, natural languages are still systematic. This means that there are rules such as syntax and grammar rules a phrase or sentence has to adhere to to be considered correct. But again, these rules have emerged over time instead of being defined a-priori. This includes that many rules can be bent until their breaking points.

As a consequence, virtually all natural languages have certain characteristics that make them very challenging for modeling or machine processing/understanding in general. These main characteristics for this discussion include:

Ambiguity: Ambiguity refers to situations where a word, phrase, or sentence can have more than one meaning, making it unclear what the speaker or writer intends. This happens because human language is flexible and often relies on context to convey the exact meaning. For example, the sentence "I saw the man with the telescope" can mean either that "I used a telescope to see the man", or that "The man I saw had a telescope". There are different types of ambiguity, such as lexical ambiguity (a single word has multiple meanings, like “bat” as an animal or a baseball tool) and syntactic ambiguity (where sentence structure creates multiple interpretations).

Expressiveness: Expressiveness refers to the ability to convey a wide range of thoughts, emotions, and ideas in rich and nuanced ways. Natural languages allow people to describe complex situations, ask questions, give commands, tell stories, and express feelings — all using a combination of words, tone, and structure. Unlike formal languages (such as programming or mathematical languages), natural language is not limited to strict rules or symbols. It can use metaphors, idioms, humor, sarcasm, and emotion, allowing people to say the same thing in many different ways.

Imprecision: Imprecision refers to the way words and phrases often lack exact or clearly defined meanings. People frequently use language that is vague or open to interpretation, which can lead to misunderstandings or the need for extra clarification. For example, saying "I'll be there soon" is imprecise because "soon" could mean in a few minutes or in an hour, depending on the context. This imprecision is part of what makes natural language flexible and easy for humans to use in everyday conversation. We rely on shared context, tone, and experience to fill in the gaps. However, this same quality makes it challenging for computers and formal systems to process natural language.

Unboundedness: Unboundedness refers to the ability to generate an infinite number of sentences and ideas using a limited set of words and rules. Thanks to grammar and syntax, we can keep building longer or more complex sentences by combining phrases, adding details, or nesting clauses. For example, you can say, "The cat sat on the mat" and expand it to "The cat that chased the mouse sat on the mat in the sun." There is no fixed limit to how much we can expand or vary what we say. This property makes natural language incredibly powerful for expressing new thoughts, describing endless situations, or asking unique questions. Even though the number of words in a language is finite, the combinations and structures we can create are practically limitless.

No Hard Rules¶

Given the "informal nature" of natural languages — and motivated by our application examples before — there is typically no single and indisputable way to detect/correct spelling or grammar mistakes, translate a sentence, transcribe a speech, and so on. In practice, this means that such natural language processing tasks cannot be solved by defining a fixed set of hard rules — or at least it would be practically infeasible to enumerate all required rules.

Instead processing and model language relies on soft rules to capture notions such as "is more likely", "is commonly preferred", or "is better" which all include a some degree of uncertainty. Uncertainty is commonly modeled using probabilities by assigning numbers to how likely different outcomes are. This helps us deal with situations where we cannot predict the outcome with certainty, but we can still make educated guesses. Language models adopt this approach and work by assigning probabilities words, phrases, and sentences. Different language models differ in the way they calculate these probabilities.

In the following, we will formalize the idea of the probability of a word, phrase, and sentence as the core concept of language models.

Probabilities of Sequences¶

The core idea of language models is to assign probabilities to sequences of words — individual words, phrases, or sentences. While the exact probability values are typically not of interest, the relative differences are used to identify the "most likely", "preferred", or "best" word, phrase or sentence, depending on the exact applications. For example, given the speech recognition application from before, our intuition is that the probability $P$ of the sentence "I ate cereal last night" should be larger than for "I ate serial last knight", i.e.:

How these probabilities are calculated depends on the type of language model; as we will outline later. However, all language models learn the probabilities from training data, ideally very large corpora of training data. In general, a language model will assign a higher probability to a sequence of words if the sequence — or its parts — do more commonly occur in the training corpus, and vice versa. For example, we would expect that the phrases "I ate cereal" or just "ate cereal" are much more common than the phrases "I ate serial" or "ate serial" (although they might exist in the training corpus even just as a typo).

In the following, we first formalize the idea of assigning probabilities to sequences of words, and then give an example how these probabilities can be calculated based on a simple training corpus.

Definitions¶

Let $S = w_1, w_2, w_3, \dots, w_{n}$ be a sequence of words $w_i$ of length $n$. Again $S$ may be a single word, a phrase, or a sentence — in fact, $S$ may contain words beyond the boundaries of sentences or paragraphs, but we limit ourselves to sentences to keep it simple. With that, we can define the probability of sequence $S$ as the joint probability of all words $w_1, w_2, w_3, \dots, w_{n}$:

Calculating joint probabilities directly is often difficult because the number of possible combinations of events (here: words) increases exponentially with the number of variables (here: number of words in $S$). The chain rule in probability is a way to break down a joint probability — the probability of multiple events happening together — into a product of conditional probabilities. It allows us to express complex probabilities in terms of simpler, step-by-step terms. For example, the joint probability of three events $A$, $B$, and $C$ happening together, written as $P(A,B,C)$, can be broken down using the chain rule as:

This means you first find the probability of $A$, then the probability of $B$ given that $A$ has happened, and finally the probability of $C$ given that both $A$ and $B$ have happened. The chain rule is used to model sequences or dependencies among variables by simplifying complex joint distributions into manageable conditional pieces. Using the chain rule we can calculate our joint probability $P(w_1, w_2, w_3, \dots, w_{n})$ as follows:

where $P(w_i|w_1, w_2,\dots ,w_{i-1})$ is the conditional probability of seeing the word $w_i$ after the sequence of words $w_1, w_2,\dots ,w_{i-1}$. All common language models calculate (or estimate!) the conditional probabilities instead of the joint probabilities directly. For example, we can calculate the probability of the sentence "I ate cereal last night" by using the chain rules as:

Of course, the question is now, how these conditional probabilities $P(w_i|w_1, w_2,\dots ,w_{i-1})$ are calculated, and different types of language models use different methods. To give some basic idea how we can calculate the conditional probabilities, we briefly introduce concept of a n-gram language model. However, note that we cover only the basic ideas here for illustration; a complete introduction to n-gram language models is the subject of a separate notebook.

Important note: The conditional probability of a word $w$ may only depend on the preceding words. Some language models — and we see an example later on — implement a bidirectional language model, where the probability of a word depends on both the preceding and the following words. Of course, these types of language models cannot be used to generate text word by word. Such language models are typically used to generate contextualized word embedding vectors.

Example: n-Gram Language Models¶

$N$-gram language models compute the conditional probabilities $P(w_i|w_1, w_2,\dots ,w_{i-1})$ by using the relative frequencies of observed $n$-grams in a text corpus. The goal is to estimate the probability of a word given its preceding words. This is done using the Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) approach, which assumes that the best estimate of a probability is the observed frequency of an event divided by the total number of relevant events.

Let's first assume $n$-grams of arbitrary sizes. The conditional probability $P(w_n|w_1, w_2,\dots ,w_{n-1})$ is then defined as

where the numerator is the number of times the full $n$-gram appears in the corpus; the denominator is the number of times the $(n-1)$-gram prefix appears. Using this definition, we can, for example calculate the conditional probability $P(\text{"night "}|\text{ "I ate cereal last"})$ as:

While this definition is sound, it cause practical challenges. As $n$ (the number of words in the sequence) gets bigger, the number of possible $n$-grams grows very quickly. This means the model would need to store and look up a huge number of combinations, which uses a lot of memory and slows things down. More importantly, in real-world data, many long word sequences do not appear often — or at all — so the model cannot learn reliable probabilities for them.

Therefore, practical $n$-gram language models rely on the Markov assumption that the occurrence of a words does not depend on all previous words in the sequence but only on the previous $k$ words (where $k$ is generally small). By limiting the size of $n$-grams — often to bigrams ($2$-grams) or trigrams ($3$-grams) — the model focuses on shorter, more common patterns that are seen often enough to make good predictions. This makes the model faster, easier to train, and less likely to run into issues with missing data.

For example, we can estimate the conditional probability $P(\text{"night "}|\text{ "I ate cereal last"})$ using bigram or trigram probabilities as shown below:

To show some concrete example calculations, let's define a toy training corpus containing the following sentences:

- "Everyone went home last night once the movie ended."

- "Sir Bedivere is often considered the last knight in Arthurian legend."

- "The last night of the year is called New Year's Eve."

- "The team finished last due to its poor performance throughout the last tournament"

No let's consider our speech recognition example where we need to decide if the we heard "I ate cereal last night" or "I ate cereal last knight". Assuming a bigram language model, we have to calculate the two conditional probabilities $P(\text{"night "}|\text{ "last"})$ and $P(\text{"knight "}|\text{ "last"})$. Of course, both relative frequencies have the same denominator of $count(\text{"last"}) = 5$ since the $1$-gram (or unigram) "last" appears five times in our training corpus. Regarding the numerators, we have $count(\text{"last night"}) = 2$ and $count(\text{"last knight"}) = 1$. Thus, we can calculate the two required conditional probabilities as follows:

Thus, given the training dataset and our bigram language model, we would say that that "night" is the more likely word among both homophones.

Summary. $n$-gram language models are fundamentally very simple and easy to implement since their training comes down to counting $n$-grams in a corpus. However, practical implementations of $n$-gram models require additional considerations to ensure a good performance. These considerations are beyond our scope here, and are subject of their own notebook covering $n$-gram language models in detail.

Types of Language Models — An Overview¶

The fundamental idea of language models is to assign joint probabilities $P(w_1, w_2, \dots , w_n)$ to sequences or conditional probabilities $P(w_n|w_1, w_2, \dots , w_{n-1})$ to words — closely linked through the chain rule. All language models als learn these probabilities from large text corpora as training datasets to express which word, phrase, or sentence is more likely to occur. However, the exact way the probabilities are calculated depends on the exact type of language model.

N-Gram Language Models¶

$N$-gram language models were first proposed in the 1950s and 1960s, during the early days of statistical approaches to language processing. However, the practical development and use of $n$-gram models for language modeling (e.g., in speech recognition and natural language processing tasks) became more prominent in the 1970s and 1980s, particularly with advances in computing and data availability.

We already saw that $n$-gram language models calculate the conditional probabilities of a word given a preceding list of words using the relative frequencies of observed $n$-grams in a text corpus. Due to sparsity in text data, $n$-gram language models typically to value of $n$ to a small value — that is, the probability of a word only depends on a few preceding words and not all preceding words. We use the same example from before to again illustrate this idea.

$N$-gram language models are simple yet effective tools for modeling language based on statistical patterns. One of their main advantages is computational efficiency: they are easy to implement and require relatively low computational resources compared to more complex models like neural networks. This makes them suitable for applications where real-time processing or limited hardware is a constraint. Additionally, $n$-gram models are interpretable — they provide clear probabilities based on observed word sequences, making them useful for understanding language patterns and debugging NLP systems. They also perform well for tasks with limited context or domain-specific language, such as autocomplete or spelling correction, especially when trained on relevant data.

However, their simplicity also means that $n$-gram language models have various limitations, mainly:

Limited context: $N$-gram models only consider a fixed window of previous words (e.g., bigrams consider one, trigrams two). This makes it difficult for them to capture long-range dependencies and broader linguistic structures, such as subject-verb agreement or discourse-level coherence, which often span more than a few words.

Data sparsity: As the value of $n$ increases — which would increase the context — the number of possible $n$-grams grows exponentially, leading to many sequences that may never appear in the training data. This results in sparse probability distributions and poor estimates for rare or unseen word combinations, even with smoothing techniques.

No generalization: $N$-gram models memorize observed sequences rather than learning abstract patterns or meanings. They cannot generalize well to new phrases or syntactic variations and struggle with word relationships like synonyms or context-based meanings.

While $n$-gram language models perform well in task that require to identify the more likely alternative (e.g., between the homophones "night" and "knight" for speech recognition); they are not suitable for text generation.

The fixed and limited context window typically leads to repetitive, shallow, and often incoherent output. Since they predict the next word based only on the previous n−1n−1 words, they cannot capture long-range dependencies, such as maintaining a consistent topic, handling complex syntax, or tracking entities over multiple sentences. This results in generated text that may be locally plausible but lacks overall structure and meaning. These limitations are key reasons why $n$-gram models have largely been replaced by neural language models.

RNN-Based Language Models¶

Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) are a type of neural network designed specifically to handle sequence data, like text, speech, or time-series information. Unlike traditional neural networks that treat each input independently, RNNs are built to remember information from earlier steps in the sequence, which makes them especially useful for understanding and generating language. In text processing, this means an RNN can take a sentence word by word and keep track of what has been said so far.

An RNN works by processing one word at a time. At each step, it takes the current word (usually represented as a embedding vector) and combines it with a hidden state that stores information from previous words. This hidden state is updated with each new word, allowing the RNN to "remember" earlier parts of the sequence as it moves forward. For example, when reading a sentence like "I ate cereal last...", the RNN updates its hidden state with each word so it can better predict what comes next, like "night".

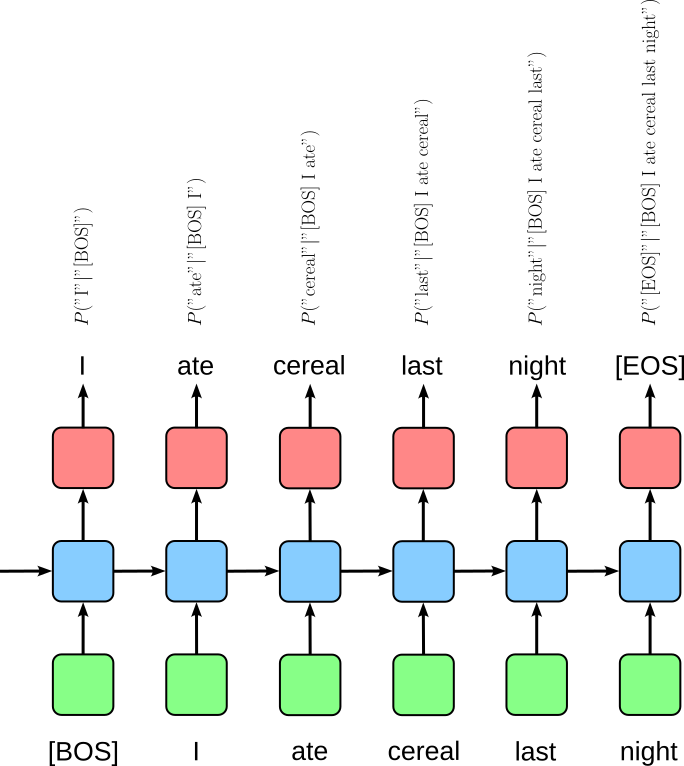

The figure below shows the "unrolled" representation of an RNN as a way of visualizing how the RNN processes a sequence step by step over time. Even though the RNN uses the same set of weights at each time step, we "unroll" it to show multiple copies of the network — one for each word in the input sequence — so we can clearly see how information flows through time. The output at each step can be used for predictions, such as the next word in a sequence.

where $\text{[BOS]}$ and $\text{[EOS]}$ are special tokens marking the beginning and the end of a sequence.

Important: Special tokens such as $\text{[BOS]}$ (beginning of sequence), $\text{[EOS]}$ (end of sequence), but also other sich as $\text{[UNK]}$ (unknown token), and $\text{[PAD]}$ (padding) are commonly used when training neural network models on text data because they provide essential structural and semantic signals that help models interpret and generate language effectively. These tokens allow models to handle variable-length input sequences, mark boundaries for decoding, manage out-of-vocabulary words, and support efficient batching and alignment of sequences. Without these markers, it would be significantly more difficult for models to understand where sentences begin or end, how to deal with missing or rare vocabulary, or how to distinguish meaningful input from padded filler during training and inference. However, the exact use and interpretation of these special tokens vary depending on the model architecture and training setup. The figure above shows a common example for an RNN that is training on a sentence-by-sentence basis.

RNN-based language models offer significant advantages over $n$-gram models, primarily because they can handle variable-length context and capture long-term dependencies in text. Unlike n-gram models, which are limited to a fixed window of $n\!-\!1$ previous words, RNNs use a hidden state that gets updated at each time step, allowing them to "remember" important information from earlier in the sequence. This makes them better suited for understanding the structure and flow of natural language, such as keeping track of subject-verb agreement or maintaining context across long sentences.

Another key benefit of RNNs is their ability to generalize better. While $n$-gram models rely heavily on exact word sequences they've seen during training, RNNs work with vector representations of words (embeddings), allowing them to learn relationships between words and handle unseen or rare phrases more effectively. This results in more fluent and coherent text generation, as the model can draw on broader patterns learned during training, not just memorized sequences.

RNN-based language models, while more powerful than $n$-gram models, also have several important limitations:

Difficulty with Long-Term Dependencies: Basic RNNs struggle to remember information from earlier in long sequences. As the input grows longer, earlier information can "fade away" due to problems like vanishing gradients during training. This makes it hard for RNNs to capture relationships between words that are far apart in a sentence or paragraph.

Sequential computation: RNNs process one step at a time, which means they can’t be easily parallelized across sequence elements. This makes training and inference slower compared to models that can process sequences all at once, like Transformers.

Training instability: RNNs are prone to vanishing and exploding gradients, especially with long sequences. Although techniques like gradient clipping and advanced variants of the RNN architectures like LSTMs and GRUs help, these issues still make training more challenging and sensitive to hyperparameters.

Limited memory capacity: Even with LSTMs or GRUs, RNNs have a limited ability to retain information over very long sequences. Their "memory" is still relatively shallow compared to newer architectures like the Transformer, which use self-attention to look at the entire sequence directly.

Because of these limitations, RNNs have largely been replaced by Transformer-based models in most modern NLP applications.

Transformer-Based Language Models¶

Transformer-based language models are a powerful type of model used to understand and generate text. Unlike RNNs, which process words one at a time in order, Transformers use a mechanism called attention that allows them to look at all the words in a sentence at once. This helps them better understand the relationships between words, no matter how far apart they are. As a result, Transformer models are faster to train, easier to scale, and more effective at capturing complex patterns in language.

There are two main types of Transformer-based language models: masked language models and causal language models. Masked language models, like BERT, are trained by hiding (or "masking") some words in a sentence and asking the model to predict them based on the surrounding words. This allows the model to learn deep understanding from both the left and right context. Causal language models, like GPT, are trained to predict the next word in a sequence using only the words that came before. This makes them especially useful for tasks like text generation, where predicting one word at a time in order is important.

Masked Language Models¶

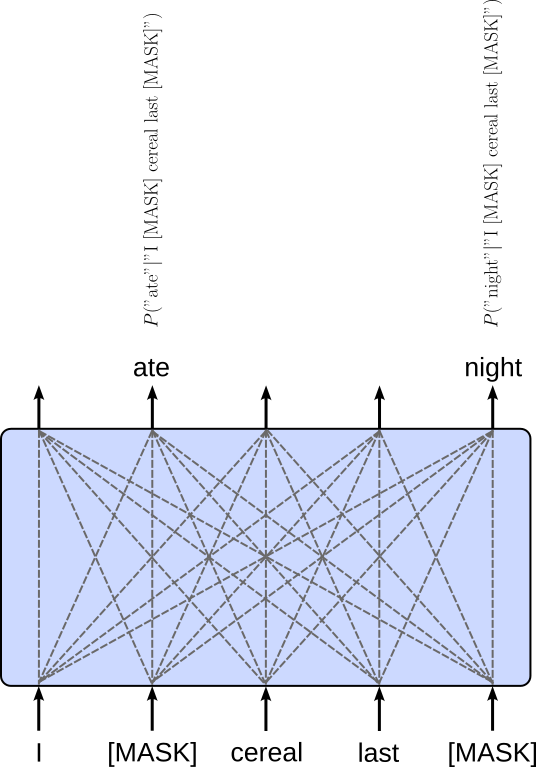

Masked language models (MLMs) are a type of language model built using the Transformer architecture, designed to help machines understand the meaning of text. Instead of predicting the next word like in traditional models, MLMs work by hiding (or "masking") certain words in a sentence and training the model to guess what the missing words are. This allows the model to learn from both the words that come before and after the masked word, giving it a bidirectional understanding of language.

For example, in the sentence "I [MASK] cereal last [MASK].", the model would try to predict the word "ate" and "night" based on the rest of the sentence provided in the training data. By doing this over millions of examples, the model learns grammar, word meanings, and relationships between words. A well-known masked language model is BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers), which became popular for its strong performance on many language tasks like question answering, sentence classification, and more. BERT uses only the encoder of the Transformer architecture. The figure below illustrates the MLM training setup of BERT using the Transformer encoder.

The dashed lines indicate the dependencies between the input and output — that is, each output word is affected by all input words as part of the attention mechanism. This includes that an output word depends on both its preceding and its following word (and the word itself). Because MLMs can look at the full context surrounding a word, they are especially useful for tasks that require a deep understanding of sentence meaning, rather than just generating new text. A trained MLM such as BERT is then used to generate contextualized word embedding vectors for input sequences.

Masked language models (MLMs) are widely used in practical applications that require a strong understanding of language context and meaning. They excel at tasks like text classification (e.g., sentiment analysis or spam detection), named entity recognition (identifying names of people, places, or organizations), and question answering, where understanding the full sentence is crucial. Because MLMs learn to fill in missing words using context from both sides, they can grasp subtle nuances and relationships in text, making them valuable for many natural language understanding tasks.

Additionally, MLMs serve as powerful pretrained models that can be fine-tuned on specific datasets for various applications, such as summarization, translation, or information retrieval. Their ability to generate rich, context-aware word representations has made them a backbone in many modern NLP pipelines, improving performance and reducing the need for task-specific training from scratch.

Causal Language Models¶

Causal language models are a type of language model built using the Transformer architecture that generate text by predicting the next word in a sequence, one step at a time. Unlike masked language models, which look at the whole sentence at once, causal models only use the words that have come before the current word to make their prediction. This makes them great for tasks like writing stories, completing sentences, or any situation where generating text in order is important.

The key idea behind causal language models is the causal (or autoregressive) attention, which means the model cannot "see" future words when predicting the next one. This mimics how humans write or speak, creating text that flows naturally and logically. Because causal language models generate text step-by-step, they are especially useful for applications like chatbots, text completion, and creative writing, where producing fluent and contextually relevant language in sequence is essential.

Most causal language models use only the decoder of the Transformer architecture. When training a language model with the Transformer decoder, the model learns to predict the next word at each step. To do this, the input and output sequences are arranged so that the model always tries to predict the word that comes right after the words it has already seen. This is done by shifting the input sequence one word or token to the left to get the target sequence. The figure below illustrates the basic training setup using the Transformer decoder:

again, $\text{[BOS]}$ and $\text{[EOS]}$ are special tokens marking the beginning and the end of a sequence. As mentioned earlier, the use of special tokens such as $\text{[BOS]}$ and $\text{[EOS]}$ may differ between tasks and training setups, and this figure above shows just one common example.

Notice that here — compared to the masked language model using the Transformer encoder — an output word only depends on the preceding words and the word itself. This is implemented using causal masking which ensures that the prediction of a word in the target sequence only depends on the previous words (and the word itself) but not any following words — without masking, the decoder processes all words in parallel and could therefore attend to future words during training, essentially "peeking" ahead and use information that would not be available when generating text in a real setting. By applying causal masking, the self-attention mechanism blocks any influence from tokens to the right (future tokens), forcing the model to learn to predict each word based solely on the words that came before it.

All modern large language models (LLMs) predominantly rely on the decoder-only Transformer architecture because it is naturally suited for autoregressive language modeling, where the goal is to predict the next word in a sequence based solely on the previous context. This architecture efficiently handles text generation by processing tokens sequentially with causal masking, enabling models to generate coherent and contextually relevant language one token at a time. Its design allows for straightforward scaling, parallel training, and strong performance across a wide range of language tasks without needing task-specific modifications. Popular LLMs using this decoder-only architecture include OpenAI’s GPT series (GPT-2, GPT-3, GPT-4), Mets' LLaMA, Google's Gemini, and Anthropic's Claude. These models have set benchmarks in natural language understanding and generation, demonstrating the effectiveness of the decoder-only Transformer in producing high-quality, fluent, and versatile text outputs.

Discussion¶

From $n$-grams over RNNs to Transformers, language models have come a long way, which shows their fundamental importance in NLP — and beyond since the Transformer architecture is now also used in other areas such as audio an image/video processing. In all practical settings, Transformer based language models have superseded $n$-gram and RNN-based language models simply due to their performance. However, despite the ability is of modern language models, they have limitations and their wide-spread popularity and use also raise ethical concerns.

Dominance of Transformers¶

All modern Large Language Models (LLMs) today are dominated by the Transformer architecture primarily because of its superior scalability, efficiency, and performance on a wide range of natural language tasks. Prior to Transformers, n-gram language models and RNN-based models were widely used. $N$-gram models, while simple and interpretable, suffer from sparsity and limited context windows, making them ineffective for modeling complex linguistic patterns or long-range dependencies. RNNs improved on this by processing sequences token by token and maintaining a hidden state, allowing for some degree of contextual memory. However, standard RNNs struggled with vanishing or exploding gradients, making it difficult to learn long-term dependencies. LSTMs and GRUs mitigated this issue somewhat, but they remained fundamentally sequential and thus difficult to parallelize during training.

Transformers, by contrast, use self-attention to compute representations for all tokens in a sequence simultaneously. This enables them to model relationships between any pair of tokens, regardless of their distance in the input, making them particularly well-suited for capturing complex linguistic structures and long-term dependencies. Moreover, the ability to train on massive datasets in parallel significantly accelerated their adoption and evolution into large-scale models like GPT, BERT, and their successors.

Another key advantage of Transformers is their modularity and extensibility. Architectures like GPT scale extremely well in terms of model depth and width, and the underlying Transformer blocks have proven versatile across modalities beyond text, including vision and audio. This flexibility has led to a rapid increase in model capabilities simply by increasing scale and training data, an approach that was far less effective with previous architectures.

However, on the flip side, training large language models using Transformers demands vast amounts of high-quality data, often in the range of hundreds of billions of words or tokens. Curating such datasets is challenging, as it requires scraping, cleaning, and filtering diverse text sources while avoiding harmful, biased, or low-quality content. Moreover, model performance tends to scale with both data and compute, meaning that increasingly larger datasets are needed to justify the scaling of model size, making the data collection and preprocessing pipeline a significant bottleneck.

On the computational side, training state-of-the-art Transformer models requires extensive resources — thousands of GPUs or TPUs running for weeks or months. This translates to high financial costs and significant energy consumption. The environmental impact is non-trivial: training a single large model can emit as much carbon as several cars do over their lifetimes. As models grow, so does concern over their sustainability, prompting research into more efficient architectures, training techniques, and the use of renewable energy sources to mitigate environmental harm.

Emerging Abilities of Modern LLMs¶

Basically all language models for generating text (e.g., GPT, LLaMA, Gemini, DeepSeek) are trained to predict the best next word. Despite this rather simple training setup, modern large language models can solve a much wider range of tasks. These so-called emerging abilities in large language models are capabilities that appear suddenly and unpredictably as the model's size and training data increase, even though they were not directly targeted during training. These abilities include tasks like multi-step reasoning, few-shot or zero-shot learning, code synthesis, arithmetic, and understanding nuanced instructions. For example, a small model might struggle with basic arithmetic or logic puzzles, while a significantly larger model — trained in the same way — can perform these tasks with surprising accuracy. These capabilities often manifest only once a certain scale threshold is crossed, a phenomenon referred to as "emergent behavior".

The reason modern large language models exhibit such emerging abilities lies in the interplay between model scale, the richness of training data, and the general-purpose nature of the Transformer architecture. As models grow in parameter count and are trained on increasingly vast and diverse datasets, they develop more sophisticated internal representations of language, knowledge, and reasoning patterns. This enables them to generalize to new tasks without explicit training. Moreover, the self-supervised training objective — predicting the next word — implicitly encourages the model to learn a wide range of linguistic and conceptual structures, some of which only become operational when the model is large and expressive enough to capture them. In essence, scale unlocks latent potential encoded in the training data, giving rise to these emergent capabilities.

Limitations of Language Models¶

Modern large language models (LLMs) like GPT-4 have achieved impressive results across a range of tasks, but they also come with significant limitations. One core limitation lies in their training objective: they are optimized to predict the next word in a sequence based on patterns in massive text datasets. While this enables them to produce fluent and contextually relevant responses, it does not guarantee that their outputs reflect objective truth. These models generate plausible-sounding information based on statistical correlations, not a grounded understanding of factual reality.

As a result, LLMs can produce confident but incorrect statements, also known as hallucinations. They may fabricate facts, misattribute sources, or provide inconsistent answers, especially when dealing with topics requiring precise knowledge or logical consistency. This unpredictability arises because LLMs do not verify information against an external database or have a stable internal world model — they simply reflect what they've seen during training, often blending truth with fiction. This emphasizes the importance of high-quality — correct, unbiased, non-toxic, etc. — training data.

Moreover, LLMs lack true reasoning capabilities. While they can mimic reasoning steps and sometimes perform well on reasoning benchmarks, this is the result of pattern recognition rather than genuine understanding or logical inference. They do not possess goals, beliefs, or the ability to reflect on their own reasoning process. Consequently, they struggle with tasks that require multi-step logic, deep abstraction, or consistency across long dialogues. Recognizing these limitations is critical when deploying LLMs in domains where factual accuracy and reliable reasoning are essential, such as medicine, law, or scientific research.

Large language models are therefore often called “stochastic parrots” to highlight the key criticism of how they function: they generate language by statistically mimicking patterns in data, without truly understanding meaning or facts. The "parrot" part of the term refers to how LLMs repeat and remix what they have "heard" (i.e., seen during training), similar to how a parrot can repeat human words without understanding them. The "stochastic" part highlights that this repetition is not exact — it is probabilistic, meaning the model generates outputs based on likelihoods rather than fixed answers. This combination makes LLMs fluent and flexible but also prone to hallucinating false or misleading information, since they lack grounding in objective truth or a conceptual understanding of what they are saying. In short, calling LLMs “stochastic parrots” is a way of emphasizing that, despite their sophisticated outputs, they are ultimately statistical machines without consciousness, understanding, or intent — just highly advanced pattern matchers.

Ethical Concerns¶

Beyond the technical challenges and limitations, there are also several significant ethical concerns surrounding large language models (LLMs), which stem from how they are trained, deployed, and used in real-world applications. These concerns span issues of bias, misinformation, privacy, environmental impact, and the potential for misuse.

Bias and discrimination: LLMs are trained on large datasets collected from the internet, which often contain harmful stereotypes, biased language, and discriminatory content. As a result, models can reproduce or even amplify societal biases related to gender, race, religion, and more. This can lead to unfair or harmful outputs, especially when used in high-stakes contexts like hiring, education, or legal decision-making.

Misinformation and hallucination: Because LLMs are not grounded in factual knowledge and only predict the next most likely word, they can generate plausible-sounding but false or misleading information — a phenomenon known as hallucination. When these models are used for generating news summaries, answering factual questions, or assisting in medical or legal advice, the consequences can be serious.

Privacy and data leakage: During training, LLMs may unintentionally memorize sensitive or personal information from the data they ingest. This raises concerns about data privacy, especially if models are trained on unfiltered internet content or proprietary datasets. In some cases, they may even regurgitate personal data when prompted in certain ways.

Environmental impact: As mentioned before, training large-scale language models consumes enormous computational resources and energy, contributing to significant carbon emissions. As models grow larger, this environmental footprint becomes a serious concern, raising questions about sustainability and the responsible use of computing power.

Misuse and malicious applications: LLMs can be used to generate deepfake text, phishing emails, disinformation campaigns, or even assist in writing malicious code. The ease with which they can produce convincing content poses security and social risks, especially when used to deceive or manipulate people at scale.

Addressing these concerns is highly non-trivial and requires a combination of technical, regulatory, and ethical strategies, including transparency in model development, better dataset curation, bias mitigation techniques, and robust guidelines for responsible use.

Summary¶

Language models are foundational tools in natural language processing (NLP) that predict the likelihood of sequences of words and generate text based on learned patterns. They are essential for tasks such as machine translation, speech recognition, text generation, and information retrieval. Understanding the development of language models helps illuminate how modern NLP systems have evolved and why they are capable of handling complex linguistic tasks today.

The earliest statistical language models were $n$-gram models, which estimate the probability of a word based on the previous $n\!-\!1$ words. Though simple and computationally efficient, $n$-gram models have significant limitations, especially in modeling long-range dependencies. They rely on fixed context windows and are prone to sparsity, meaning they often struggle with rare or unseen word sequences.

To address these limitations, RNN-based models (Recurrent Neural Networks) were introduced, enabling models to process sequences of arbitrary length by maintaining a hidden state that updates with each new word. RNNs, and later their improved variants like LSTMs and GRUs, captured sequential dependencies more effectively and marked a significant step forward. However, they still had drawbacks, such as difficulty in learning long-term dependencies and limited parallelism during training.

The introduction of Transformer-based models revolutionized language modeling. Transformers use self-attention mechanisms to process all words in a sequence simultaneously, allowing them to model relationships between distant words efficiently and enabling massive parallelization during training. This architecture laid the foundation for large-scale models like BERT, GPT, and T5, which have since dominated the field. These models can perform a wide range of tasks through fine-tuning or even in a zero-shot setting, without task-specific training.

Learning about language models is crucial because they power most modern NLP applications—from search engines and chatbots to translation systems and virtual assistants. In particular, large language models (LLMs) have demonstrated remarkable generalization capabilities, enabling them to handle tasks they weren’t explicitly trained on. Their ability to understand, generate, and reason with human language has transformed how we interact with technology and holds enormous potential for education, healthcare, software development, and more. As they continue to improve, understanding their foundations and implications becomes increasingly important.