Disclaimer: This Jupyter Notebook contains content generated with the assistance of AI. While every effort has been made to review and validate the outputs, users should independently verify critical information before relying on it. The SELENE notebook repository is constantly evolving. We recommend downloading or pulling the latest version of this notebook from Github.

Model Fine-Tuning for LLMs — An Overview¶

Fine-tuning has become a cornerstone of modern machine learning and natural language processing (NLP), particularly in the era of large-scale pretrained models. It is a form of transfer learning, in which a model trained on a massive, general-purpose dataset is further adapted to perform well on a more specialized task or within a specific domain. Rather than starting from scratch, fine-tuning builds upon the general knowledge a model has already acquired, making it far more cost-efficient and practical for real-world applications.

In the context of large language models (LLMs) such as OpenAI’s GPT series, Meta's LLaMA, or Google's PaLM, fine-tuning has proven especially significant. Pretraining equips these models with broad linguistic competence, allowing them to generate text, answer questions, and perform reasoning across a wide range of domains. However, different industries and organizations often require domain-specific adaptations. For instance, a healthcare provider might fine-tune an LLM to better handle clinical notes and medical terminology, while a legal firm could adapt the same base model to summarize case law or draft contracts with higher precision. OpenAI itself has integrated fine-tuning capabilities into its API offerings, enabling companies to refine LLMs for their unique tone, style, and use cases.

The importance of fine-tuning has also grown in tandem with the economic and technical challenges of training large models. Training a state-of-the-art LLM from scratch requires immense computational resources, datasets at web scale, and infrastructure available only to a handful of organizations. Fine-tuning, by contrast, provides a more accessible pathway to model customization. Recent innovations in parameter-efficient fine-tuning, such as LoRA (Low-Rank Adaptation), prefix tuning, and adapters, have lowered the cost barrier even further, allowing developers to achieve competitive performance with a fraction of the parameters updated. These methods make it feasible to adapt models quickly while still preserving most of the knowledge encoded during pretraining.

Given the growing ecosystem of fine-tuning methods, it is crucial for practitioners to understand when and how to apply different strategies. Full fine-tuning, for example, may be appropriate when one has sufficient domain-specific data and computational resources, whereas adapter-based or prompt-based methods are better suited for scenarios where efficiency and rapid deployment matter most. Moreover, different strategies can help mitigate risks such as catastrophic forgetting, overfitting, or unintended bias amplification. By learning the strengths and limitations of each approach, researchers and engineers can make informed decisions that maximize performance while minimizing cost and risk.

Ultimately, fine-tuning is more than just a technical adjustment; it is an enabler of innovation and personalization in AI applications. By tailoring LLMs to specialized needs, fine-tuning ensures that these models can move beyond general-purpose capabilities and deliver value in highly specific contexts. As LLMs become increasingly integrated into business processes, research, and everyday tools, mastery of fine-tuning strategies will remain essential for organizations seeking to unlock the full potential of AI responsibly and effectively.

In this notebook, we introduce the concept of fine-tuning of LLMs — but this idea is not limited to LLMs — by addressing the following three questions: (1) "What are common reasons for fine-tuning a pretrained model?" (2) "What are the main challenges of fine-tuning?", and (3) "What are common fine-tuning strategies?".

Setting up the Notebook¶

This notebook does not contain any code, so there is no need to import any libraries.

Preliminaries¶

Before checking out this notebook, please consider the following:

The concept of fine-tuning is not limited to LLMs, and many of the covered techniques are model agnostic. However, fine-tuning became particularly important due to the popularity and extreme size of modern LLMs. Hence, most examples stem from the context of language modeling and related tasks.

This notebook is intended to serve as an introduction and overview to fine-tuning. While it covers the most common strategies for fine-tuning pretrained models, many more sophisticated and specialized strategies exist, but which would go beyond the scope of this notebook.

Why Fine-Tune LLMs?¶

Training an foundation LLM from scratch is largely impractical for smaller companies or individuals due to the immense computational and financial resources required. Cutting-edge models have billions of parameters and need to be trained on massive datasets with hundreds of billions of tokens, requiring weeks of processing on large GPU or TPU clusters. The associated hardware, energy, and operational costs often run into millions of dollars, far beyond the reach of most organizations or independent researchers. In addition to infrastructure, the collection and management of the enormous, high-quality datasets required is a major challenge, demanding sophisticated data pipelines and expert oversight to avoid biases or low-quality content. Even with data and hardware, ensuring the model's reliability and safety requires deep machine learning expertise.

This is the overarching reason why smaller entities typically rely on pretrained models and adapt them through fine-tuning — there are other strategies but our focus here is in fine-tuning — gaining advanced LLM capabilities without the prohibitive costs and complexity of training from scratch. There are different more concrete reasons why a pretrained model is likely to underperform on certain tasks. Let's look at some of the most common and important ones.

Domain Adaptation¶

Large pretrained large language models (LLMs) are typically trained on publicly available, general-purpose datasets that cover a wide range of domains, styles, and topics. These datasets often include sources such as Wikipedia articles, Common Crawl web data, open-access books, GitHub repositories, and online discussion forums like Reddit. By learning from such diverse and large-scale corpora, LLMs acquire broad linguistic competence, capturing not only grammar and syntax but also factual knowledge, world concepts, and patterns of reasoning. This broad training enables them to develop a general understanding of language, allowing them to perform well on many downstream tasks without task-specific training, from text summarization to question answering and code generation.

The main problem with such pretrained models is that, while they develop a broad and general understanding of language, they often struggle with domain-specific tasks that require specialized vocabulary, nuanced reasoning, or knowledge not well represented in the pretraining data. Since the training corpora are mostly composed of general-purpose, publicly available text, these models may lack the depth of expertise or precision needed in professional and technical contexts. As a result, they risk producing outputs that are fluent and confident in tone but factually incorrect, incomplete, or misaligned with domain conventions.

Fine-tuning a pretrained model for domain adaption means to include additional training cycles using domain-specific data. One of the most common use case for domain adaptation involves companies that fine-tune an LLM with with internal, sensitive, or proprietary data that was certainly not part of the initial dataset during pretraining. Common examples include:

- Legal domain: a law firm fine-tunes a model on its own case documents and contracts so it better understands legal terminology and drafting styles.

- Healthcare domain: a hospital fine-tunes a model on anonymized patient records to improve clinical note summarization or diagnosis support.

- Financial domain: a bank fine-tunes a model on proprietary financial reports, market analyses, and transaction data to improve risk assessment or fraud detection.

- Customer support: a company fine-tunes a model on historical support tickets, FAQs, and internal troubleshooting guides so it can answer customer queries in line with company policies.

If pretrained models are used for domain-specific tasks without fine-tuning, several risks can emerge. One of the most pressing issues is hallucination, where the model generates plausible-sounding but factually incorrect or fabricated information. In high-stakes fields like medicine or law, such errors could have serious consequences, such as unsafe medical advice or misleading interpretations of legal precedents. Another risk is bias and misalignment: since pretrained models inherit patterns from their general-purpose training data, they may fail to respect domain-specific ethical, regulatory, or stylistic requirements. For example, a healthcare application must comply with strict medical guidelines, and a financial assistant must follow regulatory standards—failure to do so undermines trust and usability.

In addition, using pretrained models without domain adaptation can lead to compliance and security failures. Models trained on open web data may not be aware of industry-specific regulations, such as HIPAA in healthcare or GDPR in data privacy. Without fine-tuning, they might generate outputs that inadvertently breach compliance requirements. Furthermore, they can misinterpret domain-specific inputs, resulting in poor task performance or user frustration. These risks make clear why fine-tuning is not merely a performance booster but often a necessity for safe, accurate, and trustworthy deployment of LLMs in specialized domains.

Task Adaptation¶

Pretrained LLMs are typically not trained with task-specific supervision. Instead of being explicitly taught how to perform individual tasks such as summarization, translation, or sentiment analysis, they are exposed to vast amounts of raw, unlabeled text and learn to predict missing or next words in a sequence. This self-supervised setup enables them to acquire broad linguistic knowledge and world understanding without the need for carefully labeled datasets, which are often costly and time-consuming to produce. As a result, pretrained LLMs can serve as powerful general-purpose models that can later be adapted to a wide range of specific applications.

Two of the most common training setups are masked language modeling (MLM) and causal language modeling (CLM). In masked language modeling, used by models like BERT, a portion of the input tokens is randomly masked, and the model is trained to predict the missing words based on the surrounding context. This allows the model to learn bidirectional representations of language, capturing meaning from both left and right context. By contrast, causal language modeling, used by models like GPT or LLaMA, trains the model to predict the next word in a left-to-right manner given the preceding context. This setup directly aligns with text generation tasks, making causal models particularly effective for open-ended text completion and conversational applications. Together, these self-supervised pretraining approaches explain why LLMs possess such strong generalization abilities out of the box. However, for downstream tasks such as summarization, question answering, machine translation, sentiment analysis, and so on, pretrained models often underperform.

For example, a causal language model (CLM), trained to predict the next word in a left-to-right manner, is optimized primarily for text continuation rather than understanding or reasoning about a user's intent. Its objective is to generate the most statistically likely next token given the preceding context, which can produce fluent and coherent text but does not explicitly teach the model to interpret questions, follow multi-turn conversational context, or generate precise factual answers. As a result, when applied to question answering or chatbot-style tasks, a purely pretrained CLM may produce responses that are plausible in form but incorrect, incomplete, or misaligned with the user’s request. Moreover, CLMs lack explicit guidance on instruction-following behavior. In conversation tasks, the model must infer the user's goal, handle ambiguous questions, and manage multi-turn dialogue coherently. Since next-word prediction training does not enforce these capabilities, the model often struggles with consistency, maintaining context over multiple turns, or providing concise and relevant answers. Here are some examples for responses a CLM "only" trained to predict next word might generate for different questions:

| Question | Next-Word-Prediction Output | Issue / Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| What is the capital of France? | "France is known for its beautiful cities and culture, including many famous landmarks such as the Eiffel Tower and the Louvre Museum." | Talks about France but never explicitly states "Paris". |

| Who wrote Hamlet? | "Hamlet has been adapted into numerous plays and films over the years, with different interpretations and performances in theaters around the world." | Mentions Hamlet’s adaptations but does not identify Shakespeare. |

| How do I make a cup of tea? | "Making tea can be a relaxing experience, with many different flavors and types to choose from depending on personal preference and culture." | Gives general commentary about tea but fails to provide step-by-step instructions. |

| What is the fastest land animal? | "Animals come in many shapes and sizes, each adapted to their environment and with unique behaviors that help them survive and thrive." | Response is factually vague and does not specify a cheetah, the correct answer. |

These examples highlight why next-word prediction alone is often insufficient for tasks requiring factual, goal-directed, or instruction-following behavior. The model is trained to generate statistically likely continuations rather than select accurate answers, which is why fine-tuning or instruction alignment is critical for question answering and chat applications.

In fact, the most common use cases for LLMs — at least in the context of CLMs — involve some form of goal-directed or instruction-following tasks, where the user provides a prompt or instruction and expects a specific, useful output. This aligns with the way people naturally interact with AI: they ask questions, request summaries, seek recommendations, or ask for content generation, rather than providing a continuous stream of text for the model to predict. Because of this, the ability to follow instructions accurately is often the defining factor in whether an LLM is practically useful. As a consequence, instruction fine-tuning has become an important fine-tuning strategy because it aligns large pretrained models with human intent and diverse real-world tasks, making them far more useful and reliable in practice.

Instruction fine-tuning is closely related to task adaptation, as both involve modifying a pretrained model to perform better on downstream tasks. Traditional task adaptation usually focuses on one specific task, such as sentiment classification or named entity recognition, where the model is fine-tuned on labeled examples for that single task. Instruction fine-tuning can be viewed as a broader form of task adaptation: instead of adapting the model to one narrowly defined task, it adapts the model to understand and perform a wide range of tasks expressed through natural language instructions. In this sense, it is a multi-task adaptation strategy that leverages the general knowledge of pretrained models while making them more versatile and user-aligned. For an illustration, the table below shows an example for a simple instruction dataset.

| # | Instruction | Input | Desired Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Summarize the following text in one sentence. | "Artificial intelligence has been rapidly evolving, impacting industries from healthcare to finance and transforming the way humans interact with technology." | "AI is rapidly transforming multiple industries and human-technology interactions." |

| 2 | Translate the sentence into French. | "The weather is beautiful today." | "Le temps est beau aujourd'hui." |

| 3 | What is the capital of France? | - | "Paris" |

| 4 | Correct the grammar in the following sentence. | "She go to the store yesterday and buyed some apples." | "She went to the store yesterday and bought some apples." |

| 5 | Who wrote Hamlet? | - | "William Shakespeare" |

| 6 | Classify the sentiment of the text as Positive, Neutral, or Negative. | "I love the new design of your website—it’s very user-friendly and visually appealing." | "Positive" |

| 7 | List the first three prime numbers. | - | "2, 3, 5" |

| 8 | Rewrite the sentence in a more formal style. | "Gonna send the report ASAP." | "I will send the report as soon as possible." |

| 9 | Convert the following paragraph into bullet points. | "The company launched three new products this quarter. Each product targets a different market segment, and all have received positive customer feedback." | "- The company launched three new products this quarter.\n- Each product targets a different market segment.\n- All products received positive customer feedback." |

| 10 | Provide a short title for the following text. | "A comprehensive guide to growing organic vegetables at home for beginners." | "Guide to Growing Organic Vegetables at Home" |

A common format for a dataset used in instruction fine-tuning as shown above is a structured collection of instruction-response pairs, often with an optional input field. Each entry typically contains:

- Instruction: a natural language prompt describing the task the model should perform, e.g., "Summarize the following paragraph" or "Translate the sentence into Spanish."

- Input (optional): the data that the instruction acts upon, such as a paragraph, sentence, table, or code snippet. Some instructions, like simple questions ("What is the capital of France?"), do not require an additional input.

- Output (or Response): the desired result the model should generate when given the instruction (and input, if present). This serves as the ground truth for training.

This structured format allows models to learn how to interpret instructions and generate appropriate outputs across diverse tasks. By including a wide variety of instructions, with and without additional inputs, the dataset enables the model to generalize to unseen tasks during inference. The simplicity and flexibility of the instruction-response format make it especially suitable for multi-task adaptation, allowing a single model to handle question answering, summarization, translation, classification, and other goal-directed tasks after fine-tuning.

Continual Learning / Updating Knowledge¶

Pretrained models have a static knowledge cutoff. This means that a pretrained model only "knows" information up to a specific point in time, typically the date when its training data was last collected. After that date, it has no awareness of new events, discoveries, technologies, or social developments, etc. For instance, a model trained with data up to December 2023 would not know about events that occurred in 2024 and onwards. In practice, this limitation can cause problems when using LLMs for tasks that require up-to-date knowledge. Users might receive outdated or incorrect information if they ask about recent events, current statistics, or evolving trends. There are three main approaches to keep a pretrained model up to date with recent knowledge:

Periodic pretraining: This involves continuing the original training process of the entire model on a large, updated corpus of general text. The goal is to refresh the model's overall knowledge and capabilities so that it reflects more recent information while maintaining its general language understanding. Periodic pretraining is typically resource-intensive because it updates all model parameters and requires massive datasets and computational power — essentially, it is like giving the model a "new edition" of its general knowledge.

Fine-tuning: Fine-tuning is more targeted. It adjusts the model to perform well on a specific task, domain, or style, often using a much smaller dataset. Its primary purpose is task adaptation or domain specialization (see above), rather than updating the model's entire general knowledge. Fine-tuning is typically cheaper and faster than periodic pretraining but does not fundamentally refresh the model's broad understanding of the world. This includes that, compared to periodic pretraining, fine-tuning also comes with some additional risk and challenges, which we will discuss later

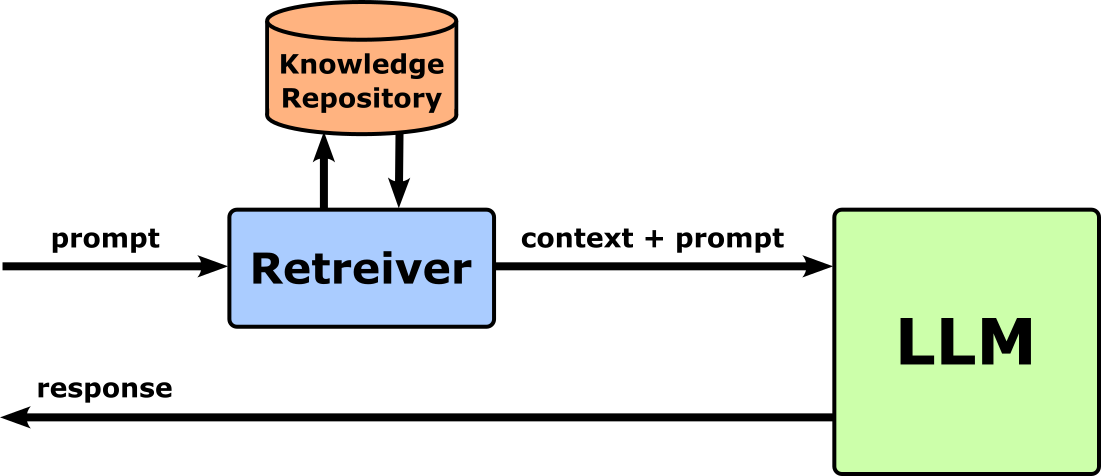

Retrieval-Augmented Generation: RAG-based approaches do not involve any actual training (i.e., no model weights get updated). Instead, RAG integrates an external knowledge source — like a database, search engine, or document store — into the generation of a model's responses. Based on an initial user prompt, the model first queries the external source at runtime, retrieves relevant documents, and uses them to generate informed answers (typically by including them in the initial prompt). This allows the model to access current information without retraining.

In practice, hybrid solutions that combine any of these three approaches are very common. However, periodic pretraining is, again, typically too costly and resource-intensive to be a viable solution for small(er) companies or organizations, let alone individuals. RAG is a very common and popular alternative approach to "show" a model data it has not seen during pretraining, but it warrants a separate discussion beyond the scope of this notebook?

Style or Tone Adaptation¶

Pretrained LLMs are primarily optimized to predict the next word in a sequence based on a vast and diverse text corpora. While this training allows them to generate coherent and contextually relevant outputs, it does not guarantee that they will consistently adhere to a specific tone or style. For instance, a model might default to a formal and explanatory register when a casual or humorous tone would be more appropriate. Similarly, when asked to draft marketing copy, an LLM might produce content that reads like an encyclopedia entry rather than persuasive advertising text. These mismatches arise because the model has not been explicitly constrained or adapted to consistently produce outputs in the desired voice.

This limitation can pose challenges for many real-world applications where tone and style are as critical as factual accuracy. In customer service, for example, a chatbot that responds in a cold, robotic tone can frustrate users and damage brand perception, even if the information provided is correct. In educational technology, a tutoring system that explains concepts too formally may fail to engage younger students who would benefit more from simple, encouraging language. Similarly, in creative writing or social media management, adhering to a consistent brand voice is essential — imagine an LLM generating a somber, academic tweet for a playful lifestyle brand. These scenarios highlight why style control is not just a cosmetic concern, but a fundamental requirement for effective communication in applied settings.

Fine-tuning allows you to adapt a pretrained LLM to consistently produce outputs in a specific tone or style by exposing it to carefully curated examples that demonstrate the desired voice. During this process, the model is retrained — typically on a smaller, domain-specific dataset — so it learns to prioritize stylistic cues over the broad range of tones it originally encountered in pretraining. For example, fine-tuning on a dataset of upbeat, conversational customer support dialogues can help ensure a chatbot responds with warmth and empathy rather than defaulting to overly formal or technical phrasing. Style and tone adaptation through fine-tuning involves continuing the training of a pre-trained language model on a new, smaller dataset of input-output pairs that exemplify the desired style or tone. The table below shows an example oto fine-tune a language model for a friendly, educational tone suitable for school children. The completions are designed to be encouraging and easy to understand, focusing on simple language and relatable analogies.

| ID | Prompt | Completion |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | What is a volcano? | That's a super cool question! A volcano is like a big mountain that has a secret, fiery heart. When it erupts, it lets out hot, melted rock called lava. Isn't that amazing? |

| 2 | How do plants grow? | Plants are like little green superheroes! They start as a tiny seed, and with the help of sunlight, water, and a little bit of dirt, they grow up tall and strong. It's like magic! |

| 3 | Why is the sky blue? | That's a wonderful question! The sky looks blue because of something called "scattering." When sunlight travels through the air, the blue light gets bounced around more than the other colors, making the sky look blue to our eyes. |

| 4 | Can you tell me a story about a friendly robot? | Once upon a time, in a world full of gears and circuits, lived a little robot named Sparky. Sparky loved to help his friends. One day, his friend Pip the bird lost his favorite shiny button. Sparky used his bright headlight to search and search until he found it, making Pip super happy! |

| 5 | What is photosynthesis? | Photosynthesis is a big word for something plants do every single day! It's how they make their own yummy food using sunlight, water, and the air around them. It's their very own kitchen inside their leaves! |

| 6 | How do I make a paper airplane? | Making a paper airplane is super fun! First, get a piece of paper and fold it in half the long way. Then, unfold it and fold the top corners into the center line. Keep folding and soon you'll have a flying machine! |

| 7 | Explain addition with an example. | Addition is like putting things together! Imagine you have 2 yummy apples. Your friend gives you 3 more. Now you have 5 apples in total! That's addition: 2+3=5. |

| 8 | What are the planets in our solar system? | The planets in our solar system are Mercury, Venus, Earth (our home!), Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune. They all orbit our giant, fiery sun! Can you say them all? |

| 9 | What is a noun? | A noun is a word for a person, place, or thing. For example, 'teacher' is a person, 'school' is a place, and 'book' is a thing. See how easy that is? |

| 10 | Who was Marie Curie? | Marie Curie was a brilliant scientist who was super curious! She loved to learn about science and she discovered two new elements. She even won a Nobel Prize, which is a huge award! She showed everyone that girls could be amazing scientists. |

For all these examples, a pretrained LLM will very likely respond with technical correct answers but typically in a much more neutral style — that is, without using simple language suitable for young school children and without the additional encouragement and playful phrases.

Bias Reduction or Custom Alignment¶

The dataset for pretraining LLMs mostly incorporates vast amounts of internet text, which inevitably contain human biases, stereotypes, and harmful language. Because these models learn patterns directly from that data, they may reproduce or even amplify such biases in their outputs. For example, when asked to generate job descriptions, an LLM might unconsciously associate certain professions with a particular gender. Similarly, when asked about cultural practices, it may provide stereotypical or one-sided explanations rather than nuanced perspectives. In more extreme cases, the model might generate unsafe or toxic content, such as misinformation, offensive jokes, or instructions for harmful activities.

This issue is critical for real-world applications where safety, fairness, and trustworthiness are non-negotiable. In healthcare, a biased or unsafe response could lead to misinformation that harms patients. In education, a tutoring system that produces culturally insensitive examples may alienate learners instead of supporting them. Even in customer service, a chatbot that generates subtly discriminatory or rude language could damage a company's reputation. These risks highlight that managing bias and ensuring safety are not just technical challenges but also ethical and practical necessities for deploying LLMs responsibly across different domains. There are different approaches to reduce biases or to align an LLM with certain values; the below lists the most common ones.

| Approach | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Data Curation and Filtering | Clean and balance training data to reduce harmful or biased patterns. | An educational tutor is trained on balanced history texts to highlight diverse cultural contributions. |

| Fine-Tuning with Curated Data | Adapt the model on datasets that reflect fairness, inclusivity, or safety. | A healthcare chatbot learns to say "people living with obesity" instead of "obese patients". |

| RLHF (Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback) | Human reviewers rate outputs for safety, fairness, and politeness, guiding the model’s preferences. | Customer service bots learn to prefer empathetic replies like "I understand how frustrating this must be" over curt responses. |

| Constitutional AI / Rule-Based Alignment | Use predefined principles or rules to guide the model’s behavior. | A Q&A assistant is constrained by rules such as "never generate hate speech" or "stay politically neutral". |

| Prompt Engineering and Guardrails | Design prompts and moderation layers to encourage safe, unbiased responses at inference time. | A financial advice assistant is prompted to "respond neutrally" and filtered to block discriminatory or unsafe outputs. |

| Post-Training Evaluation and Auditing | Test and stress-check outputs to detect bias and retrain if needed. | A recruitment support system is audited with identical resumes under different names to check for gender or ethnic bias. |

Given the focus of this notebook, fine-tuning can help reduce biases and align an LLM with specific values by retraining it on curated datasets that emphasize fairness, inclusivity, and safety. Instead of relying on the raw, unfiltered patterns from pretraining data, fine-tuning exposes the model to examples that demonstrate the desired behavior while avoiding harmful or biased responses. For instance, a model can be fine-tuned on dialogue datasets where answers are phrased in respectful, non-discriminatory language, or on instructional datasets where sensitive topics are handled with care and neutrality. Over time, this process teaches the model to prioritize these value-driven patterns in its outputs

To give a concrete example, consider that we want to ensure that an LLM generates responses that prioritizes a gender neutral language. To generating a fine-tuning datasets, we can first (a) identify sentences containing gender-specific words from an existing corpus, and then (b) replace each gender-specific word with a suitable gender-neutral alternative, if possible — Both steps can be done in a semi-automated manner, but there is some effort involved to ensure the resulting sentences are correct and well formed. The table below shows ten example pairs of a sentence written using gender-specific words and gender-neutral words.

| Gender-Specific Sentence | Gender-Neutral Sentence |

|---|---|

| The chairman will lead the meeting. | The chairperson will lead the meeting. |

| Each salesman must meet their targets. | Each sales representative must meet their targets. |

| The fireman rescued the child from the fire. | The firefighter rescued the child from the fire. |

| Every man should have the opportunity to vote. | Every person should have the opportunity to vote. |

| The actress received the award for best role. | The actor received the award for best role. |

| The stewardess served drinks on the plane. | The flight attendant served drinks on the plane. |

| A policeman will patrol the streets tonight. | A police officer will patrol the streets tonight. |

| The mailman delivered the package this morning. | The mail carrier delivered the package this morning. |

| The chairman and his assistant reviewed the report. | The chairperson and their assistant reviewed the report. |

| The businessman signed the contract. | The businessperson signed the contract. |

We can now use these gender-neutral sentences to create a dataset for fine-tuning a pretrained model, e.g., by replacing the gender-specific sentences with the gender-neutral alternatives in the original documents (or just paragraphs).

Summary: Fine-tuning a pretrained model is a powerful way to overcome its inherent limitations and adapt it to specific needs. Pretrained LLMs are trained on broad, general-purpose datasets, which means they may not always produce outputs in the desired tone, style, or level of domain expertise. Fine-tuning allows developers to address these gaps by retraining the model on curated datasets that reflect the target task, audience, or content domain. This can improve accuracy, make the model more engaging, or ensure it uses language appropriate for a particular user group. Beyond overcoming limitations, fine-tuning also enables customization and alignment. Organizations can tailor the model to their brand voice, embed domain-specific knowledge, or align outputs with ethical principles and safety standards. For example, a healthcare chatbot can be fine-tuned to provide empathetic, accurate responses, while an educational tool can adopt a friendly and age-appropriate tone. Overall, fine-tuning transforms a general-purpose LLM into a tool that is more effective, safe, and relevant for a specific application or audience.

Challenges¶

Despite its importance and potential benefits, properly fine-tuning a pretrained model to get the desired results can be very difficult in practice. After all, fine-tuning also requires datasets for training and has to deal with the challenges that come with training particularly large models. Let's break down these challenges and look at them more closely.

Data-Related Challenges¶

Compared to pretraining, fine-tuning is done using a much smaller dataset. However, the datasets needed for fine-tuning are generally not as easy to obtain as for pretraining. Recall that pretraining is typically done using large volumes of public data from the Internet. Using online data for pretraining LLMs offers major advantages due to its vast scale, diversity, and accessibility. The internet provides massive amounts of text across domains, languages, and formats, enabling models to capture a wide range of knowledge, writing styles, and perspectives. Online data is also relatively easy and cost-effective to collect compared to curated datasets, which accelerates large-scale model development and ensures broad coverage of real-world language use. In contrast, most of th time, fine-tuning requires curated dataset, which poses several practical data-related challenges:

Data availability & scarcity: Many specialized domains such as legal, medical, or financial fields lack large, publicly available, and well-structured datasets, making fine-tuning difficult. While proprietary or sensitive data may exist, its use is often restricted by privacy regulations like HIPAA or GDPR, as well as company confidentiality requirements. As a result, organizations—particularly smaller ones without access to large-scale domain corpora—face significant challenges in obtaining the necessary data to fine-tune models effectively.

Data quality & cleaning: Pretrained models are often highly sensitive to the quality of fine-tuning data, which means that noisy datasets containing typos, errors, or irrelevant content can easily lead the model to learn incorrect patterns. Ensuring clean, reliable inputs often requires significant effort, particularly in domain-specific contexts where filtering irrelevant medical records or annotating legal cases demands expert knowledge. This cleaning and preparation process is both time-consuming and costly, but essential for achieving effective fine-tuning results.

Dataset bias & representativeness: Fine-tuning datasets can introduce or amplify biases if they are not diverse or representative, leading to skewed model behavior. For example, a chatbot trained only on customer service data from one demographic may struggle to interact effectively with others or reflect narrow cultural assumptions. When the fine-tuning process focuses too narrowly, the model also risks overfitting to specific styles, reducing its adaptability and performance across broader use cases.

Labeling & annotation costs: Supervised fine-tuning, such as instruction tuning, requires large amounts of labeled input–output pairs, which are costly to produce and often demand the expertise of domain specialists like doctors or lawyers rather than crowd workers. This makes dataset creation both resource-intensive and time-consuming. Moreover, mislabeled examples can be particularly damaging, as large language models tend to heavily rely on fine-tuning data, meaning errors in annotation can significantly degrade performance.

Thus, even though fine-tuning overall requires much less data than pretraining, actually collecting, cleaning, annotating, and ensuring the quality of the dataset is often very challenging in practice. Consider the previous example of generating a dataset containing gender-neutral words to reduce gender biases by fine-tuning a model. In their paper "From ‘Showgirls’ to ‘Performers’: Fine-tuning with Gender-inclusive Language for Bias Reduction in LLMs", Bartl and Leavy generated such a dataset based on a large general-purpose dataset for pretraining use the following steps:

- Building a catalogue of gender-specific words by extracting words with suffixes -man, -manship, -woman, -womanship, -boy, -girl, and

words with the prefixes man-, woman-, boy-, and girl-. While this extraction can be done automatically, it does yield many false positives such as words which affixes did not denote gender (german, ramen, boycott), spelling errors (camerman, sopkesman), surnames (zimmerman), and other word creations (heythereman, mrfredman*). Such false positives needed to be manually identified and removed from the catalogue. In contrast, some common gender-specific words that were missing had to be manually added to the catalogue.

- Identifying gender-neutral variants for each gender specific-word in the catalogue (353 singular affixed nouns). This was mainly a manual process by (a) replacing gender-marking suffix or prefixes (e.g. chairman/-woman $\rightarrow$ chairperson), (b) using existing gender-neutral replacements (e.g., fireman $\rightarrow$ fire fighter, policeman $\rightarrow$ officer), (c) replace a word with a gender-neutral synonym (e.g., hitman $\rightarrow$ assassin), (d) identifying meaningful replacements based on the root verb (e.g., huntsman $\rightarrow$ hunter), and by simply removing gender-marking affixes if they are not needed (e.g., man-crush $\rightarrow$ crush).

While this catalogue of gender-specific words and gender-neutral alternatives can then be used to automatically replace gender-specific words in an available corpus, the creation of that word catalogue requires a significant amount of effort and consideration to ensure a high quality.

Computational Challenges¶

The most fundamental reason for fine-tuning is that training an LLM from scratch is typically prohibitively expensive beyond (very) large companies or institutions. However, this does not mean that fine-tuning does not come with its own computation challenges. While they might not be as pronounced as for pretraining large models, they are still present when fine-tuning such models in practice. The table below briefly summarizes the computational models when training (incl. fine-tuning) very large models.

| Category | Description |

|---|---|

| Resource Requirements | Large pretrained models require substantial GPU/TPU memory to store model weights and gradients. Fine-tuning often demands multiple high-end accelerators and fast interconnects, making it costly and challenging for smaller organizations without access to large-scale compute infrastructure. |

| Training Time & Efficiency | Although fine-tuning is faster than pretraining, it can still take days to weeks depending on model size and dataset complexity. Inefficient data pipelines, suboptimal batch sizes, or poor utilization of hardware can further slow training, wasting both time and resources. |

| Memory & Storage Constraints | Large models consume tens to hundreds of gigabytes of memory. Gradient updates, checkpoints, and storing multiple fine-tuned variants further increase memory and storage demands. Techniques like mixed-precision training or gradient checkpointing can help but add complexity and potential instability. |

| Scalability & Parallelization | Very large models often require sophisticated parallelization strategies (data, model, or pipeline parallelism) to distribute computation across devices. Coordinating these strategies introduces technical complexity, synchronization overhead, and potential bottlenecks that can reduce efficiency. |

| Energy Consumption & Sustainability | Fine-tuning large models consumes significant energy, increasing operational costs and environmental impact. Frequent re-tuning or experimenting with multiple variants multiplies these costs, raising concerns for sustainability and efficiency. |

Optimization Challenges¶

In general, fine-tuning means changing/updating the parameters (weights, biases, scale/shift parameters in normalization layers, etc.) of a pretrained model. Although — as we will cover later in the notebook — what parameters get updated and how, can differ quite significantly between different fine-tuning strategies, we overall change the model to elicit a different behavior. After all, this is why we want or need to fine-tune the model in the first place. But as such, fine-tuning pretrained models presents several optimization challenges that go beyond just having the data or compute resources. These challenges arise from the complex dynamics of updating a very large number of parameters while trying to achieve task-specific improvements without degrading the model's general capabilities. More specifically, although often closely related, we can distinguish between the following concerns.

Catastrophic forgetting: One of the biggest risk when it comes to fine-tuning large pretrained models on narrow datasets is catastrophic forgetting, where the model loses some of the general knowledge acquired during pretraining. This happens because standard gradient descent updates can overwrite previously learned weights, reducing the model's overall versatility. To address this, practitioners often use regularization techniques, incorporate a mix of general-domain and task-specific data, or adopt parameter-efficient fine-tuning approaches such as adapters or LoRA (discussed later), which adjust only a small subset of parameters while preserving the core pretrained knowledge.

Hyperparameter sensitivity: In general, the larger the model the more difficult it is to properly train. This includes that the model's performance can be highly dependent on choices like learning rate, batch size, weight decay, and the number of training steps. Setting the learning rate too high may destabilize training or overwrite previously learned knowledge, while setting it too low can lead to extremely slow convergence. Identifying the optimal hyperparameters typically involves trial-and-error or systematic hyperparameter searches, which can be computationally intensive and time-consuming, especially for very large models.

Overfitting & underfitting: Like with training models in general, and closely related to catastrophic forgetting, a common challenge also in fine-tuning large pretrained models is balancing overfitting and underfitting. When fine-tuning on small or narrow datasets, the model may overfit, achieving high accuracy on the training data but performing poorly on new, unseen examples. On the other hand, insufficient fine-tuning can lead to underfitting, where the model fails to capture the task-specific patterns and underperforms overall. To address this, strategies such as early stopping, data augmentation, and regularization are used to control model complexity and improve generalization. These techniques help ensure the model effectively adapts to the new task without losing its broader pretrained capabilities.

Gradient instability: Another challenge when working with very large models in general means fine-tuning large pretrained models can encounter gradient instability, where gradients either explode or vanish, particularly in deep architectures or when using high learning rates. This instability can lead to training divergence, slow or poor convergence, and unpredictable model behavior. To mitigate these issues, techniques such as gradient clipping, learning rate scheduling, and mixed-precision training are commonly employed. These approaches help stabilize training, ensuring that the model updates remain controlled and effective throughout the fine-tuning process.

Task misalignment & conflicting objectives: A notable challenge in fine-tuning large pretrained models is task misalignment and conflicting objectives. Pretrained models are generally optimized for broad language modeling, so adapting them to a specific task — especially one that differs significantly from the pretraining data — can create conflicting learning signals. This misalignment may lead to slower convergence or suboptimal performance on the target task. This often requires careful loss function design and curriculum strategies, gradually guiding the model from general knowledge toward task-specific behavior. These techniques help the model adapt more smoothly, reducing conflicts between its pretrained capabilities and the new task requirements.

In essence, fine-tuning still has to deal with all the challenges when it comes to training very large models (hyperparameter sensitivity, overfitting & underfitting, gradient instability). However, since we do not train a model from scratch but "tweak" a pretrained model, we now also risk the model in unintended ways which can result in negative effects such as catastrophic forgetting, task misalignment, and conflicting objectives.

Ethical & Safety Challenges¶

Fine-tuning large pretrained models raises a number of ethical and safety challenges because it changes the way these systems behave and can unintentionally compromise safeguards built into the base model. One of the most pressing concerns is bias amplification. Pretrained models already contain biases from their training data, but fine-tuning on smaller, domain-specific datasets can make those biases more pronounced. For example, if the fine-tuning data underrepresents certain groups or perspectives, the resulting model may produce outputs that are unfair, discriminatory, or unrepresentative. In high-stakes applications like hiring, healthcare, or education, this can have tangible harmful consequences.

Another challenge lies in content safety and harmful outputs. Even if the base model has been aligned to avoid generating toxic or unsafe content, fine-tuning can unintentionally weaken those guardrails. Models adapted with uncurated or noisy datasets may start producing offensive, misleading, or unsafe responses. For example, a model fine-tuned for customer service might begin giving inappropriate or harmful advice if its dataset contains unchecked toxic language. This risk is particularly acute in sensitive domains such as mental health support, legal guidance, or public information systems, where incorrect or harmful outputs could cause real-world harm.

Fine-tuning also increases the risk of misuse and malicious applications. By lowering the technical barrier to creating highly specialized models, fine-tuning allows individuals or organizations to adapt powerful systems for harmful purposes, such as spreading disinformation, generating targeted harassment, or creating malware and phishing content. The openness of many fine-tuning techniques means that well-intentioned innovations can also be repurposed by bad actors. This dual-use dilemma underscores the need for governance, monitoring, and responsible access policies around fine-tuning tools and datasets.

Lastly, there is the problem of value misalignment and loss of safety features. Pretrained models are often aligned with broad safety and ethical principles during their initial development, but fine-tuning may shift the model’s objectives away from these principles. For instance, optimizing purely for task performance can override safety trade-offs, causing the model to prioritize efficiency over ethical considerations. Without mechanisms like reinforcement learning with human feedback (RLHF), safety layers, or careful dataset design, fine-tuning risks producing systems that no longer adhere to societal norms or user expectations. Addressing these challenges requires not only technical safeguards but also organizational practices such as dataset audits, transparency, and continuous evaluation to ensure models remain both effective and responsible.

Evaluation Challenges¶

Large language models (LLMs) trained on the next-word prediction task are commonly evaluated using a mix of intrinsic metrics and extrinsic benchmarks. Intrinsically, their performance is often measured by perplexity, which measures how well a model predicts the statistical likelihood of the next word. This makes perplexity a well-defined and objective measure. Evaluating LLMs beyond perplexity is challenging because language quality and usefulness are inherently multidimensional and subjective. Perplexity measures how well a model predicts the statistical likelihood of the next word, but it does not reflect whether outputs are factually accurate, logically consistent, contextually appropriate, or safe. For example, a model might achieve low perplexity yet generate fluent but misleading or harmful text. Capturing these higher-level qualities requires more complex evaluation frameworks that go far beyond raw predictive accuracy.

Another difficulty is the lack of universally agreed-upon benchmarks for many aspects of language generation. Tasks like reasoning, creativity, or open-ended dialogue do not have single "correct" answers, making automatic metrics such as BLEU, ROUGE, or accuracy inadequate. Human evaluations can better capture nuance but are expensive, time-consuming, and inconsistent across raters. Even preference-based comparisons, where humans judge which of two outputs is better, introduce cultural and contextual biases. As a result, evaluating LLMs often requires a combination of automated metrics, curated benchmarks, and human assessments, but designing this mix to fairly and reliably capture real-world performance remains a major open challenge.

In fact, these challenges are often even more pronounced when it comes to fine-tuning which is often done for domain, task, or style/tone adaption. In the common use case for domain adaption where a company fine-tunes a model using its internal and often sensitive data, reliably evaluating for correctness and accuracy is very difficult. The evaluation of models that have been fine-tuned to adopt a certain tone or style is often particularly subjective. For example, consider our previous use case where we want to fine-tune a pretrained language model to reply to questions in a friendly, educational tone suitable for school children. It is not obvious how to evaluate the effectiveness of the fine-tuned model as there are no clear measures of "friendliness" and what constitutes "friendly enough" or maybe even "too friendly". In short, while fine-tuning itself is challenging, actually showing that the fine-tuning was indeed successful is also far from straightforward.

Fine-Tuning Strategies¶

There are various ways to categorize fine-tuning strategies. One perspective is the adaptation goal, which defines the purpose and direction of the model adjustment. So just to summarize the section about reasons for fine-tuning pretrained models: Domain or task adaptation approaches aim to enhance the model's performance on specific types of data or particular tasks. These approaches ensure that the model becomes more accurate and relevant for specialized applications, such as legal document analysis, medical diagnosis, or sentiment classification in niche industries. The focus here is on tailoring the model to perform well in a concrete, often narrow, context. In contrast, instruction and alignment approaches focus on shaping the model's behavior to better follow human instructions and align with desired outputs. For example, instruction fine-tuning involves training the model on datasets containing instructions and corresponding responses, enabling it to respond appropriately to a wide range of user queries. While domain/task adaptation improves performance on specific content or tasks, instruction and alignment approaches enhance the model's general usability, responsiveness, and adherence to human expectations across diverse tasks.

From the perspective of the learning paradigm, fine-tuning strategies differ in how many tasks a pretrained model is adapted to handle. In single-task fine-tuning, the model is optimized for a specific task, such as sentiment analysis or summarization. This approach is straightforward and usually yields strong performance on the chosen task but can limit generalizability to others. By contrast, multi-task fine-tuning adapts the model jointly across several tasks, encouraging it to learn shared representations and transfer knowledge between domains. This often improves efficiency and robustness but requires careful balancing of task objectives to prevent one task from dominating the learning process. Finally, continual or sequential fine-tuning involves adapting the model to new tasks or domains over time, which reflects how real-world applications evolve. These main paradigms highlight the trade-offs between specialization, versatility, and long-term adaptability when fine-tuning large pretrained models.

However, the most fundamental way to categorize different fine-tuning strategies is regarding the scope of parameter updates — that is which parameters of the pretrained model get updated during fine-tuning. Some strategies may only update a subset of the model parameters, while other strategies first extend the model with additional parameters and (typically) update only those. In this section, we will introduce the most common fine-tuning strategies and discuss their pros and cons.

Full Fine-Tuning¶

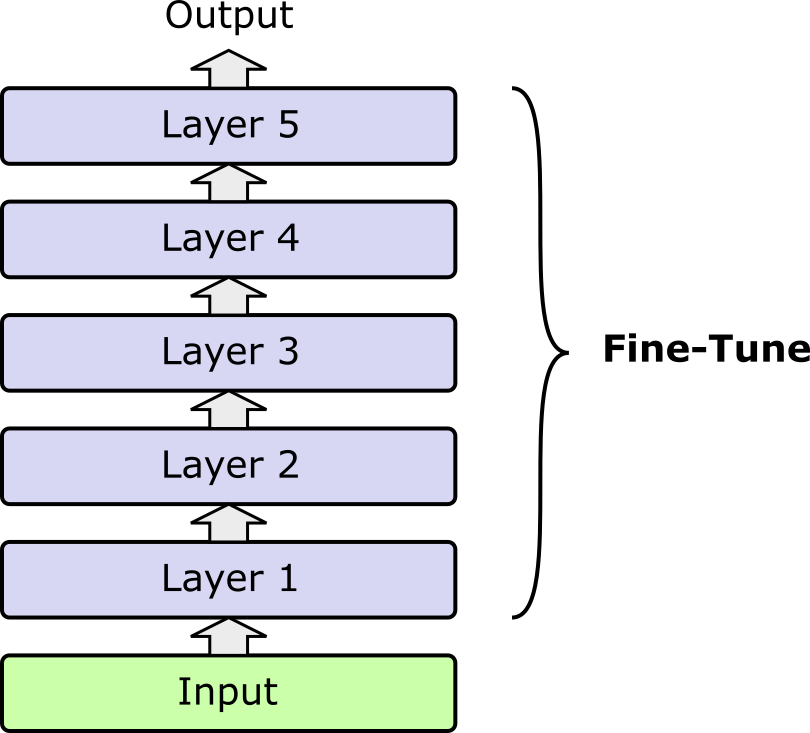

Full fine-tuning means taking a pretrained model — such as a large language model trained on massive amounts of general text — and updating all of its parameters on a new dataset so that it adapts fully to a specific task or domain. The following figure illustrates this idea by assuming a network with five layers (e.g., 5 transformer layers in a transformer encoder or decoder), where all the weights in all the layers get updated during fine-tuning.

Since full fine-tuning allows every weight and bias in the model to shift during training, this gives the model the maximum flexibility to learn new patterns, correct limitations from pretraining, and align more closely with the target tasks requirements. The main strength of full fine-tuning is performance: since the entire network can adjust, it often yields the best results when there is enough high-quality task-specific data. For example, fine-tuning a general model on biomedical literature allows it to capture specialized terminology and reasoning patterns far beyond what lightweight methods can achieve. However, this flexibility comes at a cost. Training is computationally expensive, requires significant storage for multiple fully fine-tuned copies, and risks overfitting or catastrophic forgetting of the model's general knowledge.

Because of these trade-offs, full fine-tuning is typically reserved for high-value tasks with abundant data and resources, or when peak performance is critical. In many practical scenarios, organizations opt for parameter-efficient methods instead, which preserve most of the pretrained model while only learning small task-specific additions. Still, full fine-tuning remains the most direct and powerful way to repurpose a pretrained model for a new purpose.

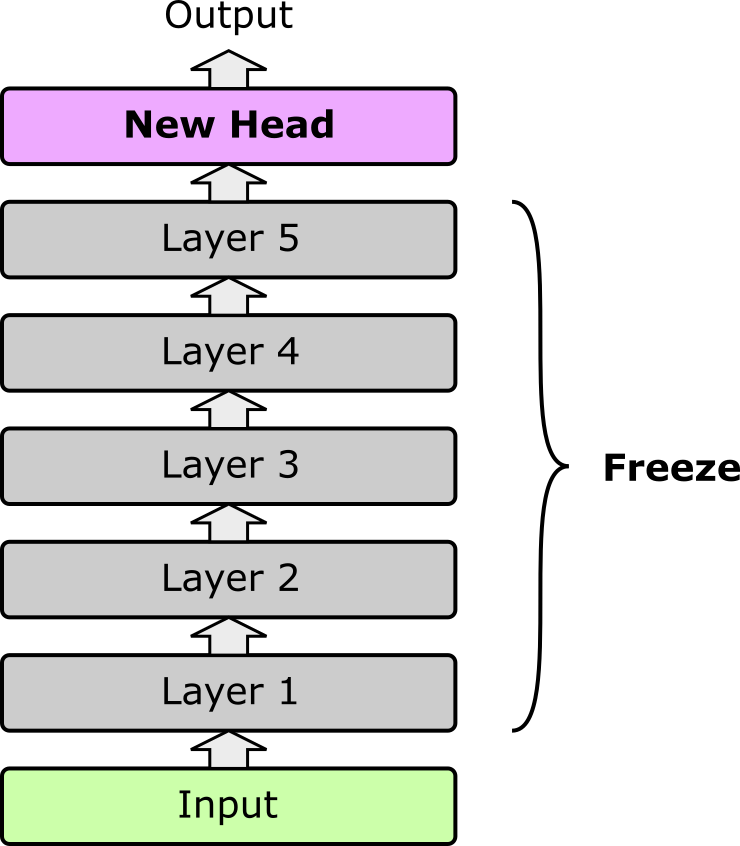

Partial or Selective Fine-Tuning¶

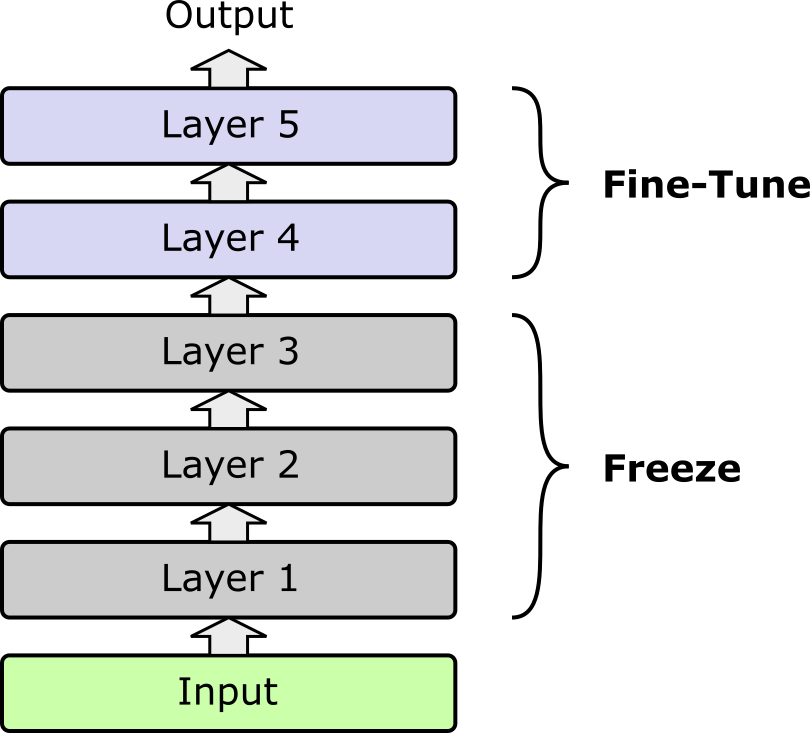

Partial or selective fine-tuning is an intermediate approach between full fine-tuning and parameter-efficient methods. Instead of updating all the parameters of a pretrained model, only a subset — typically the last few layers — are fine-tuned on the target task, while the earlier layers remain frozen. The rationale is that early layers usually capture general features (e.g., edges in images, syntactic patterns in text) that are broadly useful across tasks, whereas later layers encode more task-specific representations. By updating only the later layers, the model can adapt to new tasks without losing the general knowledge captured during pretraining; the figure below illustrates this idea.

Partial fine-tuning balances performance and efficiency. Because fewer parameters are updated, training requires less computation and memory compared to full fine-tuning. It also reduces the risk of overfitting to the limited target data and helps preserve the pretrained model's generalization capabilities. For instance, in a Transformer-based LLM, the lower transformer layers might remain frozen while only the top layers are fine-tuned for sentiment classification or domain-specific text generation.

Partial fine-tuning is widely used in practice when computational resources are limited or when the target dataset is small. It often provides performance that is close to full fine-tuning, particularly when the pretrained model's lower-layer representations are sufficiently rich. Moreover, it offers a compromise between flexibility and stability: the model adapts to the new task without completely overwriting its pretrained knowledge. This makes selective fine-tuning a practical choice for many real-world applications.

Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning (PEFT)¶

Parameter-efficient fine-tuning (PEFT) is a strategy that adapts a pretrained model to a new task by updating only a small subset of parameters or adding lightweight trainable modules, while keeping the majority of the original model frozen. Common PEFT methods include LoRA (low-rank updates to weight matrices), adapters (small layers inserted between frozen layers), and prompt tuning (learning continuous input embeddings). The main advantage is efficiency: PEFT drastically reduces the number of trainable parameters, saving computation and storage, and allows a single base model to be reused for multiple tasks. Despite modifying only a small portion of the model, PEFT often achieves performance comparable to full fine-tuning, especially when the pretrained model already contains rich representations.

Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA)¶

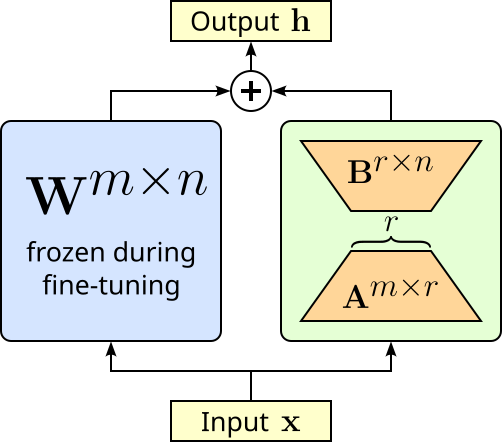

LoRA. LoRA adapts large pretrained models by adding small, trainable low-rank matrices to certain weight matrices — typically in the attention and feed-forward layers — while keeping the original weights frozen. Instead of updating the full weight matrix $\mathbf{W}^{m\times n}$ (which can be very large), LoRA learns two much smaller matrices $\mathbf{A}^{m\times r}$ and $\mathbf{B}^{r\times n}$ whose product approximates the necessary update $\Delta \mathbf{W} = \mathbf{AB}$, which then yields the final output of the layer $\mathbf{h} = \mathbf{W} + \Delta\mathbf{W}$. The matrices $\mathbf{A}$ and $\mathbf{B}$ have dimensions chosen so that the rank $r$ is much smaller than the original matrix size, drastically reducing the number of trainable parameters. The figure below illustrates the idea of LoRA.

Matrix $\mathbf{A}$ is typically initialized with some random Gaussian noise,i.e., $\mathbf{A} \sim \mathcal{N}(0, \sigma^2)$), while matrix $\mathbf{B}$ is initialized with all elements being $0$, i.e., $\mathbf{B} = 0$. This means that at the beginning of the fine-tuning $\Delta\mathbf{W} = 0$ so that the output of the layer is only determined by the original weight matrix $\mathbf{W}$. Of course, during the fine-tuning, matrices $\mathbf{A}$ and $\mathbf{B}$ will get updated during backpropagation so that $\Delta\mathbf{W} \neq 0$. To better illustrate this idea, let's consider a simple linear layer containing $10$ neurons and expecting an input of size $10$. When implemented, this linear layer features a weight matrix $\mathbf{W}^{10\times 10}$ looking as follows:

This means that the weight matrix of this linear layer contains $100$ trainable parameters in total — however, those are frozen and not update during fine-tuning. LoRA now adds two matrices $\mathbf{A}^{m\times r}$ and $\mathbf{B}^{r\times n}$; let's assume $r = 3$. We now have two matrices $\mathbf{A}^{10\times 3}$ and $\mathbf{B}^{3\times 10}$ which are added to the model as illustrated above. Again, let's quickly visualize both matrices.

Both matrices $\mathbf{A}$ and $\mathbf{B}$ now contain $30$ values each; thus, a total of $60$ trainable weights — compared to initial number of $100$ weights in $\mathbf{W}$. More generalized, weight matrix $\mathbf{W}$ contains $mn$ values, matrices $\mathbf{A}$ and $\mathbf{B}$ contain together $(mr+rn)$ or $r(m+n)$ values. During fine-tuning, only these $60$ parameters in weight matrices $\mathbf{A}$ and $\mathbf{B}$ are updated. Note that, in practice, the number of trainable parameters $\mathbf{A}$ and $\mathbf{B}$ are much smaller than the number of parameters in $\mathbf{W}$ since $\mathbf{W}$ is much larger in pretrained LLMs; there is therefore more potential in reducing the number of parameters.

Adaptors¶

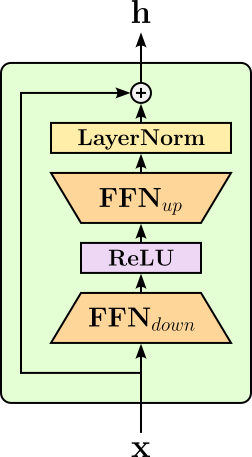

In general, adapters are small, trainable neural network modules inserted into the layers of a large pretrained model to enable task-specific adaptation without modifying the original model's parameters. During fine-tuning, only the adapter parameters are updated, while the vast majority of the model's weights remain frozen. Typically, an adapter is a bottleneck layer that projects the high-dimensional hidden states of the model down to a smaller dimension, applies a nonlinearity, and then projects them back up to the original dimension before passing them to the next layer. This allows the adapter to learn compact task-specific transformations while keeping the base model intact. The figure below shows a simple adapter in the form of a bottleneck layer.

Here, the first fully connected network (FFN) layer maps the input down into a lower-dimensional representation. After applying a non-linear activation function, a second FFN layer maps the activation back up into the same dimension of the input. The example above also performs layer normalization (LN) at the end — while the adapters can be arbitrarily complex, simple modules as shown here are very common. Adapters also have a residual connection so they can adjust the pretrained model's representations without overwriting them, preserving the general knowledge learned during pretraining while adding small, task-specific refinements. This design also helps with stable training as the output starts as identical to the pretrained hidden state, the fine-tuning process can gradually incorporate task-specific modifications instead of making abrupt changes to the model's internal representations.

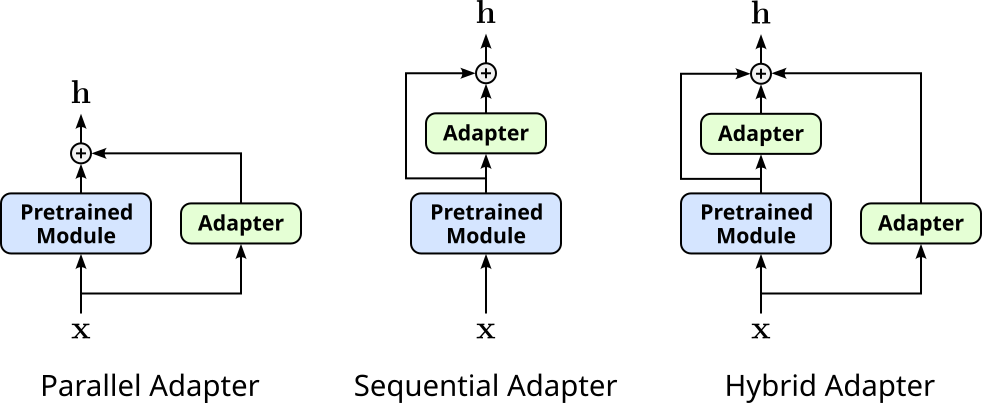

Adapters can then be inserted into a pretrained model parallel to existing layers, sequentially (i.e., between existing layers), or both (hybrid). The following figure illustrates the basic setup for all three alternatives.

You may notice that parallel adapters are very similar to LoRA, and in some sense they are closely related. However, adapters are complete modules (i.e., small sub networks with linear layers, activation functions, normalization layers, etc.) and are inserted parallel to complete modules of the pretrained model. In contrast, LoRA "only" inserts low-rank approximations parallel to a single weight matrix, typically of a single linear layer.

Although commonly used for fine-tuning to LLMs, both LoRA and adaptors are general PEFT strategies. Other such strategies are more specific to LLMs. For example , prompt tuning "tunes" or optimizes a set of special, learnable tokens, known as soft prompts, which are prepended to the input text. These soft prompts act as a kind of "task-specific context" that guides the frozen, pre-trained model toward the desired output. Unlike traditional prompt engineering, where humans manually craft the prompts, prompt tuning automatically learns the optimal soft prompts for a given task, making the process much more scalable. Prompt tuning only adjusts these much smaller soft prompts during the training process. This means the original model remains untouched and retains its general knowledge. When a new input comes in, it is combined with the optimized soft prompt, and the model's pre-existing knowledge is leveraged to solve the new task. Prefix tuning is very similar to the idea of prompt tuning. Both methods adapt a large pretrained LLM by learning a small set of task-specific continuous vectors (i.e., the soft prompts). The main difference is where these soft prompts are inserted. In prompt tuning, the learned vectors are prepended to the input embeddings only once before the first Transformer layer. They act like extra tokens that influence the model’s behavior through all subsequent layers, but no additional parameters are added deeper in the network. In prefix tuning, the idea goes further: instead of adding the soft prompts only at the input, a learned "prefix" is injected into the key and value matrices of the self-attention mechanism in every transformer layer. This means that at each layer, the model can attend to both the real sequence tokens and the layer-specific prefix vectors. Each layer has its own prefix parameters, allowing for more fine-grained control over the model's internal attention patterns. Because of this deeper integration, prefix tuning often performs better than prompt tuning on complex generation tasks, especially in low-data settings. The trade-off is that prefix tuning generally involves more parameters than prompt tuning (since each layer has its own prefix) and can be a bit more computationally expensive at inference.

Related Strategies¶

Full fine-tuning, partial fine-tuning, and parameter-efficient fine-tuning are not only strategies to address the limitations of pretrained models by means of domain or task adoption. Let's look at some popular alternatives that are strictly speaking not fine-tuning strategies but have very similar goals.

Feature Extraction (Frozen Model + New Head)¶

Feature extraction is one of the simplest ways to leverage a pretrained model for a new task. In this approach, the pretrained model is kept frozen, and its role is to act purely as a fixed feature extractor. Input data is passed through the model, and the output representations (often embeddings from the last hidden layer) are used as features. On top of these fixed features, a new trainable head — such as a linear classifier, multilayer perceptron, or other lightweight module — is added and trained on the target dataset. Since only the head's parameters are updated, training is computationally cheap and avoids altering the pretrained weights. The figure below shows the idea (assuming the same simple 5-layer pretrained model we saw for full and partial fine-tuning).

The motivation behind feature extraction is that pretrained models, whether in vision, language, or multimodal domains, already encode general and transferable representations. Early and intermediate layers capture broad features (e.g., edges and textures in vision models, syntax and semantics in language models), while later layers provide semantically rich embeddings. By reusing these representations, feature extraction makes it possible to achieve strong performance on new tasks without retraining the full model or requiring massive amounts of labeled data.

Common applications include image classification with pretrained CNNs (e.g., using ResNet embeddings with a new classifier head), text classification or sentiment analysis using frozen language model embeddings (e.g., BERT's [CLS] token output feeding into a classifier), and speech recognition or audio classification using pretrained acoustic models. In many applied settings (e.g., medical imaging, customer feedback analysis, or recommendation systems—feature extraction provides a practical, resource) efficient way to adapt powerful pretrained models to specialized tasks.

Retrieval-Augmented Generation¶

Retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) is an approach that enhances pretrained language models by combining them with an external knowledge retrieval system. Instead of relying solely on the model's internal parameters — which are limited to what it learned during pretraining and its knowledge cutoff — RAG dynamically retrieves relevant documents or passages from a large knowledge base when generating responses. The model then conditions its output not just on the user’s query, but also on the retrieved context. This helps the model produce more accurate, up-to-date, and grounded answers without needing to retrain or fine-tune the entire network. The figure below shows the most basic RAG setup. The retreiver receives the initial prompt and fetches relevant documents from the knowledge repository. This context together with the initial prompt is then passed to the LLM to generate the response.

The strength of RAG lies in separating knowledge storage from reasoning and generation. The external retriever provides factual and current information, while the pretrained model focuses on understanding the query, reasoning over the retrieved content, and generating a coherent answer. This not only reduces hallucinations but also makes updating knowledge as simple as refreshing the retrieval database, rather than retraining the model itself.

Common applications include question answering systems (e.g., chatbots retrieving from Wikipedia or enterprise knowledge bases), customer support (retrieving company-specific FAQs and documentation), legal or medical assistants (grounding outputs in domain-specific databases or research literature), and search-augmented generative tools (such as code assistants retrieving from documentation or forums). In practice, RAG has become a key method for building trustworthy and domain-adapted AI systems.

Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF)¶

Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF) is a technique used to align large pretrained models with human preferences, values, or task requirements. Instead of training only on static datasets, RLHF leverages human-provided feedback to guide the model’s behavior. The process typically unfolds in three stages: first, a base model is fine-tuned on supervised instruction-response pairs to provide a starting point. Second, a reward model is trained using human feedback, where annotators rank multiple model outputs by preference. Finally, reinforcement learning (commonly Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO))is used to optimize the model so that it generates outputs that maximize the reward model's scores, effectively aligning it with human judgment. In more detail, the three stages perform the following tasks:

Stage 1: Fine-tune a retrained model. This stage typically involves instruction fine-tuning (see above). Here, prompts are sampled from a dataset and given to human annotators to write the reference response. The resulting prompt-response pairs are then used to fine-tune the pretrained model.

Stage 2: Train a reward model. Again, prompts are sampled from the dataset and given to the fine-tuned model. For each prompt, the fine-tuned model generates multiple responses. All responses for a prompt are then given to a human annotator to rank them with respect to the annotator's preference. This dataset of ranked responses is the used to train a reward model that scores a response based on human preferences.

Stage 3: Update model through RL. New prompts are given to the fine-tune model. The responses are scored by the reward model, and reinforcement learning strategies are used to update the model based on those scores. The goal is that the model is more likely to generate responses that are preferred by humans in the future.

The key idea is that pretrained models may be capable of producing coherent text, but their outputs can be unhelpful, misleading, unsafe, or misaligned with what users actually want. Human feedback provides a way to bridge this gap. By repeatedly scoring or ranking outputs, annotators encode preferences such as helpfulness, factual correctness, safety, and tone. The reinforcement learning step then fine-tunes the model's generative policy, nudging it toward producing outputs that humans would find most appropriate.

The strength of RLHF lies in its ability to make large models more aligned, safe, and user-friendly without requiring explicit rules for every possible scenario. This is important because language models operate in open-ended environments where human expectations are nuanced and context-dependent. While traditional supervised fine-tuning may teach a model how to perform tasks, RLHF ensures it performs them in a way that matches human intentions and values.

Common applications include chatbots and conversational assistants (e.g., aligning responses to be helpful and polite), content moderation systems (guiding the model to avoid harmful or biased outputs), creative writing tools (tuning outputs to reflect specific stylistic preferences), and instruction-following models (like modern large language models that interpret user queries accurately). RLHF has become a cornerstone of safe and effective deployment of AI systems, particularly in consumer-facing applications.

Summary¶

Fine-tuning pretrained models has become the dominant strategy in modern machine learning because training large models, such as large language models (LLMs), entirely from scratch is impractical to impossible for most individuals, organizations, and even many research labs. The cost, scale of data, and computational resources required are beyond the reach of all but the largest corporations and institutions. Instead, pretrained models serve as a powerful foundation: they already capture broad knowledge and representations from massive datasets, and fine-tuning provides a way to adapt these models to specific tasks, domains, or user needs without incurring the prohibitive cost of full pretraining.

The benefits of fine-tuning are significant. By building on an already capable model, practitioners can achieve strong performance on specialized tasks with much less labeled data and computation. Full fine-tuning allows the entire model to adapt, often yielding the best performance for complex domains. Selective or partial fine-tuning strikes a balance between flexibility and efficiency by updating only certain layers. Parameter-efficient fine-tuning (PEFT) methods, such as adapters, LoRA, or prompt tuning, minimize storage and compute requirements, making it possible to maintain multiple task-specific adaptations of a single base model. Even lighter approaches like feature extraction make it possible to use pretrained embeddings directly with new classifiers, offering quick and resource-efficient solutions.

At the same time, fine-tuning comes with challenges. Data-related issues — such as obtaining sufficient high-quality, domain-specific annotations — can limit effectiveness. Computational demands, while lower than training from scratch, can still be substantial, especially for full fine-tuning of very large models. Fine-tuned models may also suffer from catastrophic forgetting, where adapting to a new task erases some of the pretrained model’s prior knowledge. Furthermore, optimization challenges arise in ensuring stable convergence and preventing overfitting, particularly when fine-tuning on small datasets.

Overall, fine-tuning pretrained models represents the most practical and powerful pathway to deploying machine learning systems that are both cost-effective and high-performing. It democratizes access to cutting-edge AI by allowing smaller organizations and individuals to adapt massive pretrained models for their own purposes, while still requiring careful attention to efficiency, data quality, and alignment with task goals. In this way, fine-tuning stands at the intersection of scalability and specialization, making modern AI development feasible far beyond the handful of institutions capable of training models from scratch.