Disclaimer: This Jupyter Notebook contains content generated with the assistance of AI. While every effort has been made to review and validate the outputs, users should independently verify critical information before relying on it. The SELENE notebook repository is constantly evolving. We recommend downloading or pulling the latest version of this notebook from Github.

Resource-Efficient LLMs — An Overview¶

The rise of large language models (LLMs) has shown their enormous potential in natural language understanding, reasoning, and generation. However, this progress has come with extremely high computational and memory costs. Training state-of-the-art LLMs often requires thousands of GPUs running for weeks, with costs reaching into the millions of dollars, while inference demands large-scale infrastructure to serve users at low latency. This makes efficiency a central challenge: without innovations that reduce these costs, only a handful of well-funded organizations could realistically build or deploy such models, limiting accessibility and slowing down innovation.

Improving efficiency is not only about lowering costs but also about enabling new capabilities. More efficient training methods allow researchers and practitioners to experiment with larger models, longer context lengths, and richer modalities, pushing forward what LLMs can do. Similarly, efficient inference strategies make it possible to deploy LLMs at scale in real-world applications such as interactive assistants, code generation tools, or scientific analysis systems. Without efficiency gains, many of these applications would be impractical due to latency, hardware limitations, or energy consumption.

For developers and researchers, learning about efficiency strategies is crucial because it directly impacts feasibility and competitiveness. Techniques such as sparse attention, quantization, low-rank adaptation, distributed training, or speculative decoding are no longer optional optimizations but necessary tools to make LLMs usable in practice. Understanding these strategies allows practitioners to make informed trade-offs between accuracy, cost, and scalability, tailoring models to the constraints of their organizations or deployment environments.

Finally, efficiency has broader societal and environmental implications. Reducing the computational footprint of LLMs decreases energy consumption and carbon emissions, aligning AI development with sustainability goals. At the same time, efficiency democratizes access, allowing smaller companies, academic groups, and individual developers to contribute to the field rather than being excluded by prohibitive costs. For these reasons, ongoing efforts to improve the efficiency of LLMs are not only technically important but also central to ensuring the responsible and widespread adoption of this transformative technology.

In this notebook, we will go through wide range of common strategies that have been proposed and are deployed to improve the efficiency of LLMs. While each of these strategies are a topic on its own, this notebooks serves as "entry point" to explore the landscape of optimizing LLMs in terms of their computational costs, their memory footprint, and environmental impact.

Setting up the Notebook¶

This notebook does not contain any code, so there is no need to import any libraries or other external code

Preliminaries¶

The purpose of this notebook is to provide a basic overiew to common strategies to improve the efficiency of LLMs. The content is therefore on a fairly high level focusing to convey the basic idea. We adopt the paper "Efficient Large Language Models: A Survey" for the organization of the following content.

Apart from a small section outlining some alternative architectures, all proposed strategies are either specific to the Transformer architecture (mainly focusing on the attention mechanism) or are completely architecture agnostic. This includes the strategie may be more applicable to encoder-only LLMs (e.g., BERT), encoder-decoder LLMs (e.g., T5), or only decoder-only LLMs (e.g., GPT, LLaMA, Gemini).

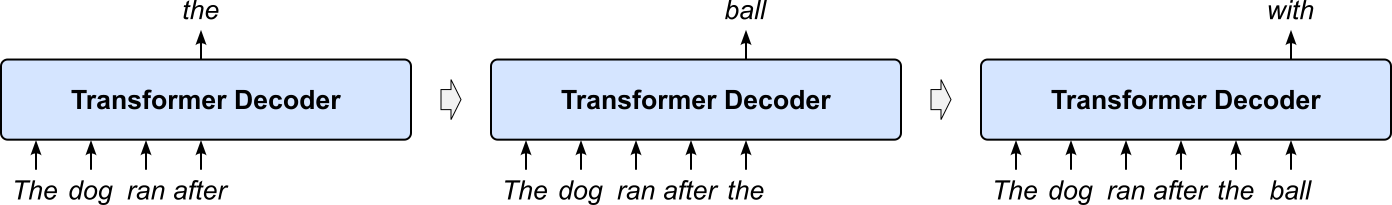

Since we focus on the original Transformer, we assume text as input. To make all visualizations, examples, and descriptions easier to understand, we assume that any input text is tokenized into proper words. Note that practical Transformer-based models typically rely on subword-based tokenizers (e.g., Byte-Pair Encoding, WordPiece).

Overall, we assume that you already have some solid understanding about the Transformer architecture and Transformer-based LLMs.

With these clarifications out of the way, let's get started...

Model-Centric¶

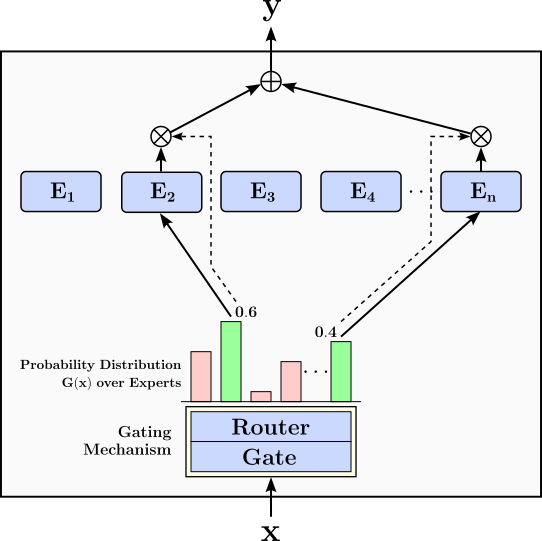

Model-centric strategies focus on improving the design and parameterization of LLMs themselves to achieve better efficiency without fundamentally changing the training or inference pipelines. These approaches aim to make the model more compact, expressive, and resource-friendly by rethinking how parameters are used. Examples include pruning redundant weights, quantizing parameters to lower precision, and employing low-rank factorization techniques (such as LoRA) to reduce the cost of fine-tuning. Other strategies involve architectural innovations like parameter sharing, mixture-of-experts (MoE) layers that activate only subsets of the model, or sparsity-inducing mechanisms that lower the effective compute per token.

The core idea is that by optimizing the model's internal structure, one can reduce memory footprint, speed up computation, and lower energy costs while retaining most of the performance of larger dense models. Model-centric efficiency makes training and deployment more accessible by reducing hardware requirements and enabling faster iteration. It also allows practitioners to adapt large pretrained models to new domains or tasks more efficiently, making them practical for real-world applications where cost, latency, and scalability are critical factors.

Model Compression¶

The main determiner of the size of a large neural networks such as an LLM in terms of memory footprint is the number of parameters it contains. Each parameter typically represents a weight in the model and requires storage (usually 16-bit or 32-bit floating point). For example, a model with 1 billion parameters using 32-bit floats would need roughly 4 GB just to store the weights. As models grow to hundreds of billions of parameters (like GPT-3 or GPT-4), the memory requirements increase proportionally, significantly impacting GPU/TPU memory usage during both training and inference. In addition to parameters, activations during inference or training can further increase memory usage, especially in multi-layer transformers where intermediate outputs must be stored. However, the parameter count remains the primary factor in the static memory footprint (i.e., the model size on disk or when loaded).

The goal of model compression is to reduce the memory footprint, either by reducing the number of parameters or reducing the required memory to store the parameters. In principle, model compression will always result in some loss of information. The reason why model compression techniques do not significantly harm the performance of a model is because (very) large models are often over-parameterized. This means these models have more trainable parameters than are strictly necessary to fit the training data or solve the target task. In other words, the model has more capacity than the complexity of the dataset requires. LLMs are often over-parameterized by design. These models typically have billions to trillions of parameters, far exceeding the minimum needed to fit their training data. This over-parameterization gives them a high capacity to learn complex patterns, subtle linguistic nuances, and world knowledge from vast datasets — and it makes quantization a practical solution to reduce the memory footprint of the model.

Let's go through some of the most popular approaches to compress large models to reduce their memory footprint.

Parameter Pruning¶

Parameter pruning is a technique used to reduce the size of large neural network models by removing weights or connections that contribute little to the model's performance. The basic idea is that not all parameters in a neural network are equally important — some have a negligible effect on the output. Recall that the output or activation $a_i$ of a single neuron is the weighted sum of its inputs, followed by the application of (typically) nonlinear activation function $f$; more formally:

where $x_1$, $x_2$, ..., $x_d$ are the inputs of the neuron and $w_{ji}$ are the $d$ trainable weights. The intuition is that very small weights are unlikely to have any significant effect on the output and can therefore be ignored. However, there are also other possible considerations to identify "unimportant" weights. The most common strategies to identify which weights can be pruned fall into a few key categories, each based on different assumptions about the importance of weights or structures in the neural network:

Magnitude-Based Pruning: This is the most widely used and straightforward method. Weights with the smallest absolute values are pruned under the assumption that they contribute least to the model’s output. It can be applied globally (across the entire model) or layer-wise. This method is especially common in unstructured pruning.

Gradient-Based Pruning: This approach evaluates the importance of weights based on how much they affect the loss function. One common method is to calculate the product of a weight and the gradient of the loss with respect to that weight (e.g., using Taylor expansion approximations). Weights with a small impact on the loss are pruned.

L1 or L2 Norms (Structured Pruning): For pruning larger structures like entire neurons, filters, or attention heads, importance can be judged by computing the L1 or L2 norm of the associated weights. For example, convolutional filters with lower norms might be considered less important and removed as a whole.

Sensitivity Analysis / Saliency Scores: These methods assess how sensitive the model’s performance is to the removal of individual weights or structures. Saliency scores, derived from Hessian approximations or influence functions, attempt to estimate this impact more precisely, though they are computationally more expensive.

Learned Pruning (Trainable Masks): In this method, binary masks are learned jointly with the model weights to identify which connections can be zeroed out. Techniques like variational dropout or L0 regularization fall into this category, where sparsity is encouraged as part of the training objective.

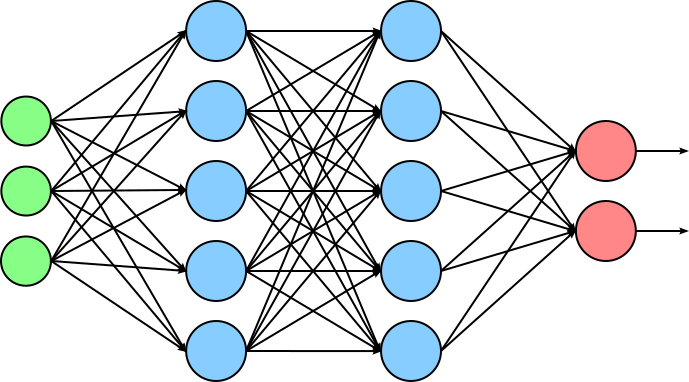

Each strategy has its own trade-offs between simplicity, computational cost, and pruning effectiveness, and often they are combined with retraining or fine-tuning to regain any lost accuracy. The pruning itself can be done in two different ways, unstructured and structured. Let's briefly introduce both approach and highlight their differences by using the following simple network:

In this figure, the green nodes represent the input, the blue nodes represent the neurons of the two hidden layers, and the red nodes represent the neurons of the output layers. The arrows between nodes reflect the number of trainable weights of the network; we ignore the biases to keep the illustration simple.

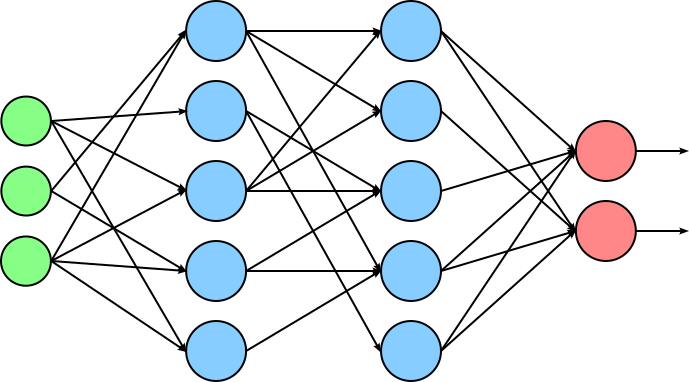

Unstructured Pruning. In unstructured pruning, the goal is usually to introduce sparsity into the model by setting a certain percentage of the smallest-magnitude weights to $0$, assuming these have minimal influence on the model's output. Because it operates at such a fine-grained level, unstructured pruning can often achieve high compression ratios with little accuracy loss — especially when combined with retraining (or fine-tuning) to recover performance. We can visualize the setting of weights to $0$ by removing those weights from out architecture:

Setting a weight to $0$ only removes the value in case of sparse representations of weight matrices. However, most general-purpose hardware (like GPUs and TPUs) is optimized for dense matrix operations, not sparse ones. As a result, even if many weights are zeroed out, the model still requires dense memory storage and compute time unless custom sparse kernels or specialized hardware are used. In short, unstructured pruning does not inherently compress models in a hardware- or storage-efficient way, but it plays a critical role in analyzing model redundancy, reducing overfitting, and preparing models for more advanced compression pipelines.

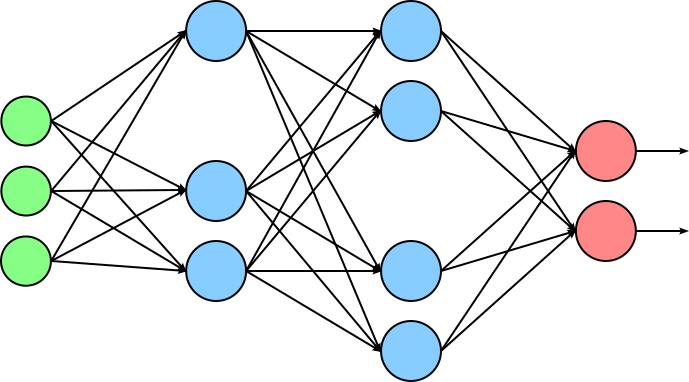

Structured Pruning. In structured pruning, entire structures within a neural network — such as neurons, channels, filters, attention heads, or even whole layers — are removed, rather than just individual weights. The key idea is to eliminate coherent groups of parameters that contribute the least to model performance. The figure below illustrates this idea; notice how three neurons have been removed from the hidden layers of the original model as part of the pruning step.

Structured pruning is especially valuable for achieving practical speedups and memory savings. Because the resulting model maintains a dense format with smaller dimensions — for example, the weight matrices of the two hidden layers in our pruned example network are now smaller — the model can be run efficiently on existing hardware like GPUs and TPUs without the need for sparse-specific optimizations. Structured pruning is often guided by importance metrics, such as the L1 or L2 norms of filters, attention scores, or sensitivity analyses. Once pruning is done, the model is usually fine-tuned to recover any accuracy lost due to the removal of structures. Structured pruning is widely used in real-world deployments of deep learning models, particularly in scenarios with strict latency or memory constraints (e.g., mobile devices, edge computing, or embedded systems). It offers a practical path to model compression that balances performance, simplicity, and hardware efficiency.

While structured pruning can lead to real improvements in speed and memory usage, it also has some downsides. One major challenge is that removing large parts of the model can hurt accuracy, especially if the pruned components were important. It can also be hard to tell which parts of the model are truly unnecessary, since common pruning methods often rely on rough estimates. Another issue is that pruning can create imbalances between layers, causing bottlenecks that limit performance. To avoid this, careful planning and retraining are usually needed, which adds extra time and cost. And even though structured pruning is more hardware-friendly than unstructured pruning, the actual speedups still depend on how well the pruned model fits the target hardware.

Quantization¶

The most common representation of trainable parameters during training is 32-bit floating-point (fp32) precision. This is because fp32 offers a high level of numerical precision and dynamic range, which is crucial for stable and accurate gradient calculations during backpropagation. Training deep neural networks involves many small and incremental updates to the weights, and fp32 helps ensure that these updates are not lost due to rounding or precision errors. Although mixed-precision training using formats like fp16 is becoming more popular — especially for speeding up training and reducing memory usage on compatible hardware fp32 is still widely used as the default in many frameworks because it provides more robust and reliable convergence, especially for complex models or tasks that are sensitive to numerical precision.

The issue is that fp32 requires $4$ bytes to store a single value, resulting in huge memory requirements in case of models with millions, billions, or even trillions of trainable parameters. To give some examples, the table below shows the number of trainable parameters and the required memory assuming fp32 precision (32 bits = 4 bytes per parameter) for some popular LLM architectures:

| Model | Parameters (approx.) | Memory @ fp32 (GB) |

|---|---|---|

| GPT-2 (large) | 774 million | ~3.1 GB |

| GPT-3 | 175 billion | ~700 GB |

| LLaMA 2 (7B) | 7 billion | ~28 GB |

| LLaMA 2 (13B) | 13 billion | ~52 GB |

| LLaMA 2 (70B) | 70 billion | ~280 GB |

| GPT-4 (est. 1T range) | 1 trillion (est.) | ~4,000 GB (4 TB) |

Note that the memory usage here is only for model weights in fp32. During training, additional memory is required for activations, gradients, optimizer states (e.g., Adam uses 3 times the weight size), so actual training memory can be 4-8 larger.

During inference, however, the neural network is no longer updating its parameters — it is simply using the learned weights and biases to compute outputs. This allows the use of reduced-precision formats (such as fp16, int8, or bfloat16) for the weights, biases and activations (i.e., intermediate outputs of neurons/layers), because small rounding errors introduced by lower precision generally do not significantly affect the final predictions. The model's structure and learned representations are typically robust enough to tolerate minor numerical approximations. For an every-day analogy, consider the following quote from a PyTorch blog post:

If someone asks you what time it is, you don’t respond "10:14:34:430705", but you might say "a quarter past 10".

This process of reducing the precision of trainable parameters and activations of (mostly) trained models for inferencing is called quantization. The general goal of quantization is to map high-precision values (e.g., fp32) to low-precision values of smaller range (e.g., int8). while preserving the overall distribution of values during the mapping.

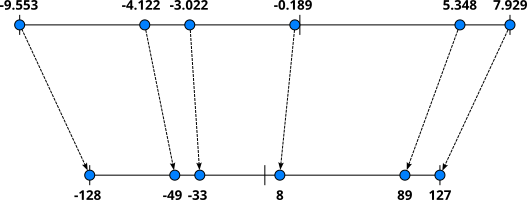

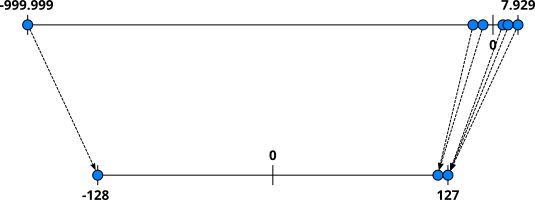

Apart from the chosen target precision, there are also various quantization strategies. One basic strategy is asymmetric quantization. In asymmetric quantization, we first find the minimum and maximum parameter value in a weight matrix. We then find a linear mapping $f(x)$ that maps the minimum and maximum parameter values to the range of the target precisions. For example, let's assume we want to quantize a weight matrix containing fp32 ($4$ bytes) values to int8 ($1$ byte) values; the range of int8 is $-128$ to $127$. Let's further assume that the minimum and maximum values in our fp32 weight matrix are $-9.533$ and $7.929$. Ignoring the details, it is relatively straightforward to find a linear mapping $f(x)$ such that $f(-9.533) = -128$ and $f(7.929) = 127$. We can then use $f(x)$ to convert all fp32 values in the weight matrix to int8 values. The figure below illustrates this idea.

Since we convert fp32 to int8 in our example, we can reduce the required memory by about 75%. The table below extends the previous table by including now the approximate memory requirements when representing the trainable parameters as int8 values.

| Model | Parameters (approx.) | Memory @ fp32 (GB) | Memory @ int8 (GB) |

|---|---|---|---|

| GPT-2 (large) | 774 million | ~3.1 GB | ~0.77 GB |

| GPT-3 | 175 billion | ~700 GB | ~175 GB |

| LLaMA 2 (7B) | 7 billion | ~28 GB | ~7 GB |

| LLaMA 2 (13B) | 13 billion | ~52 GB | ~13 GB |

| LLaMA 2 (70B) | 70 billion | ~280 GB | ~70 GB |

| GPT-4 (est. 1T range) | 1 trillion (est.) | ~4,000 GB (4 TB) | ~1,000 GB (1 TB) |

Again, these numbers refer only to the trainable parameters of the model — although those are the only ones that matter during inference. Keep in mind, however, that a full int8 quantization may not apply to all parts of the model (e.g., some layers might still use fp16/fp32), so real-world memory use can be slightly higher.

While basic asymmetric quantization and similar variants are relatively easy to implement in terms of finding and applying mapping $f(x)$, there are some practical challenges involved. One of the biggest problems are outliers, i.e., extreme values in the weight matrix. Since the minimum and maximum values in our weight matrix, outliers "artificially" increase the input range and negatively affect the definition of $f(x)$. To illustrate this, let's assume that the weight matrix from our previous example contains an outlier $-999.999$ as the new minimum. Using the same approach as before, we might get a mapping as illustrated by the figure below.

Particularly notice how now non-ouliers are mapped into a very small range in the target precisions, and many values are now more likely mapped to the same value, making them unable to distinguish any longer. These effects greatly increase the risk of performance degradation due to quantization. A basic counter-measures is clipping, where all fp32 weight values are cut to a minimum and maximum range. However, finding good cut-off values is not straightforward and typically requires some form of calibration. The main take-away message is that even basic strategies such as asymmetric quantization require careful considerations and implementations to minimize the degradation of performance of a quantized model.

On a high-level, quantization strategies come in three main flavors:

Post-Training Quantization (PTQ): In PTQ, the network is training using full precision (e.g., fp32) and the trainable parameters are converted to a lower-precision format (e.g., int8) after the model has been fully trained. As such, PTQ does not require retraining the model making It simpler and faster to implement, but may lead to slightly lower accuracy, especially in very sensitive models, compared to QAT.

Quantization-Aware Training (QAT): QAT simulates the effects of quantization (e.g., converting to int8) during the training process, rather than after training like in PTQ. The basic idea is to insert "fake" quantization operations into the computation graph that mimic the rounding, clamping, and precision loss of real quantization, allowing the model to learn to adapt to these constraints. During QAT, the model still uses fp32 weights and activations for backpropagation and gradient updates, but forward passes include simulated quantization effects. This helps the model adjust its parameters to reduce the accuracy loss that would otherwise occur due to quantization. As a result, QAT typically achieves higher accuracy than post-training quantization, especially in cases where the model is sensitive to precision loss.

Quantized Training (QT): QT (or integer-only training) is a more advanced form of quantization where both the forward and backward passes of training are performed using low-precision (e.g., int8) that will be used during inference. Unlike QAT, which simulates quantization effects but still uses float32 for gradients and weight updates, QT aims to train the entire model using quantized operations. However, this approach is much more challenging due to the difficulty of accurately computing gradients and performing updates with limited precision, and it often requires special techniques like custom optimizers, quantized gradient representations, and careful scaling strategies.

Overall, quantization is a useful approach to reduce the overall memory footprint of a model in a predictable manner. Quantization generally works best for (very) large models (incl. LLMs) as those models are more likely to be over-parameterized, and the reduced precision is likely to harm the model's performance. Still, quantization always involves some loss of information which may result in the degradation of the performance of a model. To help mitigate performance degradation, meaningful quantization strategies are required that take issues such as outliers into consideration.

Knowledge Distillation¶

Knowledge distillation (or model distillation) relies on the same observation as quantization — that is, the very large models are often over-parameterized and have more capacity than the complexity of the dataset or task requires. For example, foundation LLMs have billions and trillions of parameters, and have been trained over Web-scale datasets. Using such a general-purpose LLM to power, say, a domain-specific chatbot is often overkill. For such use cases — which are very common — a much smaller model with way less computational costs would often suffice.

The obvious alternative would be to train a smaller model and use mostly training data relevant to the target domain (e.g., a chatbot helping customers of a bank). However, training even a small(er) LLM from scratch is still very challenging and resource-intensive as the model not only has to learn the domain knowledge but also proper language, including the underlying complex patterns and subtle linguistic nuances, to generate well-formed sentences and paragraphs. On the other hand, we already have much larger foundation models that "know" language. So why not utilize this knowledge?

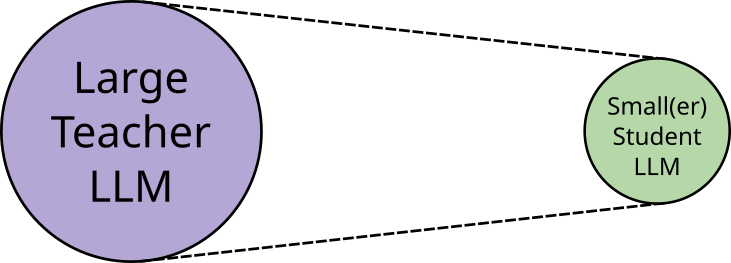

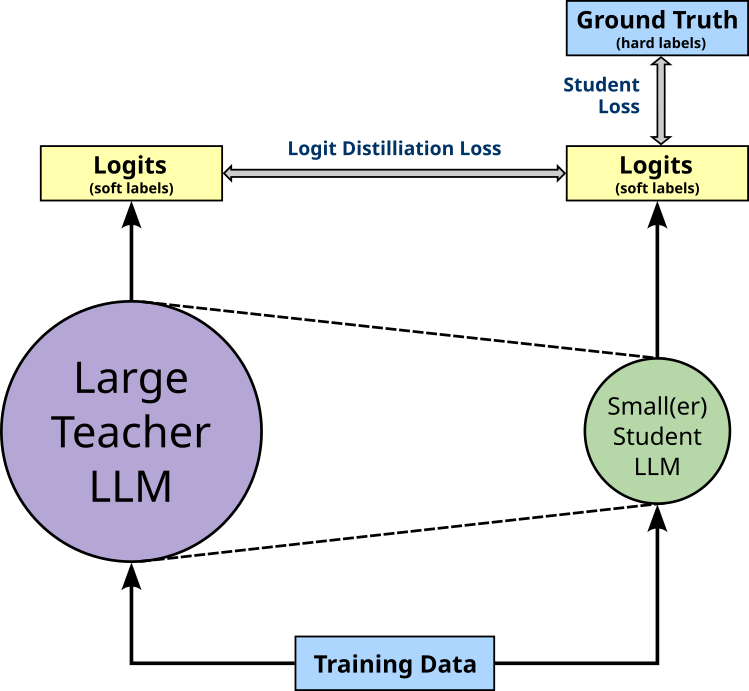

This is where knowledge distillation comes in. At its core, knowledge distillation, is about transferring knowledge from a large, complex "teacher" model (e.g., out pretrained foundation LLM) to a smaller, simpler "student" model; the figure below illustrates this overall idea. The teacher model is typically overparameterized and computationally expensive. The intuition is that the teacher model has learned a rich representation of the data (e.g., text and language). Instead of training the student model from scratch, it learns by mimicking output of the teacher model. This essentially guides the student model to learn a similar behavior as the teacher model but with much fewer trainable parameters.

There are various implementations of knowledge distillation to use a large teacher model for training a small(er) student model. Why implementation of knowledge distillation is applicable mainly depends on the available (domain-specific) training data, whether the trainable parameters of the teacher model are accessible (white box) or only the outputs of the teacher model can be used (black box), and the overall computational resources. Let's briefly go through some of the common approaches for knowledge distillation.

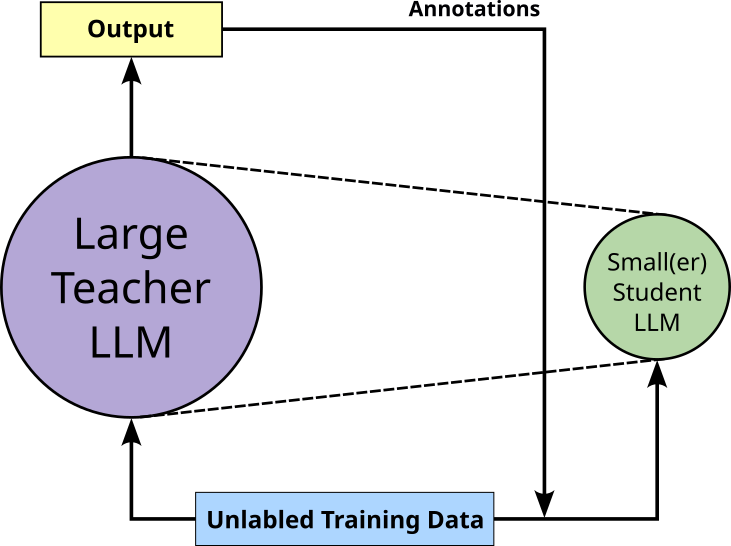

Response Distillation. The fundamental idea of response distillation is simply to use the teacher model to annotate an unlabeled dataset which is then used to train the student model; see the illustrations below. In other words, instead of manually annotating or creating the training dataset for the student model, we use the teacher model to "outsource" this task. For example, in case of the LLM, the unlabeled training data may consist of questions and the annotation provided by the teacher model are the corresponding answers.

Response distillation is very easy to implement, particularly if the teacher model is accessible via an API and, for example, there is no need to run a teacher LLM locally. This makes response distillation a black-box approach since no parameters or activations of the model are required. Assuming a good teacher model — which is the most fundamental assumption for knowledge distillation, the annotations provided by the teacher model are generally of high quality.

However, response distillation has its limitations and challenges. For one, creating annotations for large datasets needed to train the student model can be quite expensive, either in terms of compute or money (e.g., when using a paid API). Also, the final output of the teacher model does not capture more nuanced knowledge (compared to logits; see below) which often means the trained student tends to be less creative in terms of its responses to prompts. And lastly, response distillation requires that the teacher model was exposed to all relevant data during training to create correct annotations (e.g., answers to questions). This implies that we cannot use response distillation to train a very domain-specific model based on data not part of the training of the teacher model.

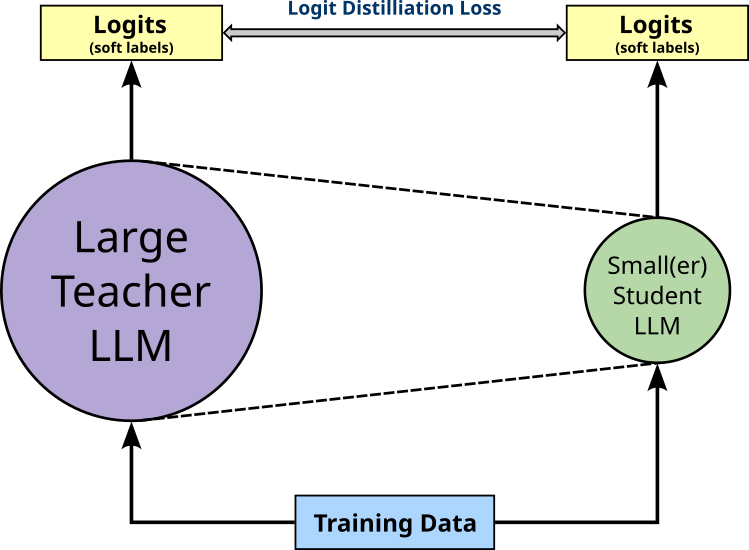

Logits Distillation. In case of logits distillation, both the teacher and student model receive the same input (e.g., a text prompt). Training the student model means to ensure that the output of the student model better and better mimics the output of the teacher model. As the name suggests, logits distillation considers the final logits as the outputs of both models. The reason is that the logits capture more information than the probabilities after the Softmax. Additionally, particularly in case of LLMs, it is much less straightforward to compute the similarity or the differences between the final text outputs. The logits of a model are generally considered internal values of a model, making logits distillation a black-box approach.

Logits distillation comes in two flavors. Logits distillation with teacher supervision only considers only the similarity or differences between the logits of both models. Training the student model here means minimize some logits distillation loss (e.g., KL Divergence) to make the student mimic the teacher; see the figure below.

As such, this form of logits distillation does not require an annotated dataset. Of course, this again means that the quality of the student model will highly depend on the quality of the teacher model. Without any ground truth, it generally makes it more challenging to properly evaluate the trained student model.

In contrast, if an annotated dataset containing ground truth is available, logits distillation with student loss can be implemented. Here both a distillation loss and the basic student loss — typically the cross-entropy loss between the predicted and ground truth labels — are minimized together to train the student. The figure below illustrates this extension to the overall setup.

Including the basic student loss typically provides a richer training signal resulting in a more stable training, and allows for a straightforward evaluation using common metrics. Of course, considering both losses also adds complexity to the training. This includes that it is not obvious how both loss terms should be combined, and typically weight terms are used to balance between the importance of both losses. Lastly, there is the risk of conflicting signals when the output of the teacher model is very different than the ground truth. This can happen if the training data used for the distillation contains data completely unknown to the teacher model. Whether the output of the teacher model or the ground truth should be more trusted can be tweaked by the weight terms when combining both losses.

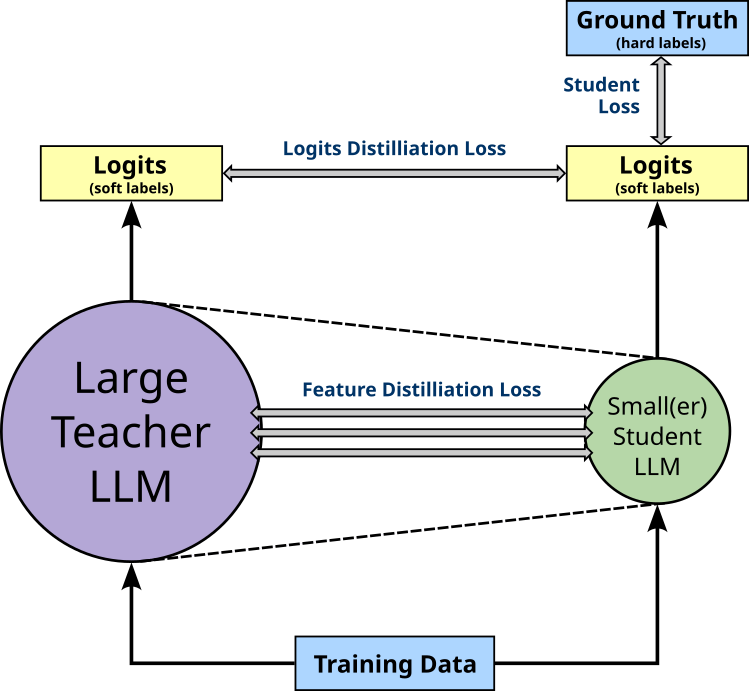

Feature Distillation. In feature distillation, the student model not only aims to mimic the teacher model with respect to the output, but also with respect to the internal representations (features or parameters). As such, feature distillation also minimizes the loss with respect to different activations (i.e., intermediate outputs) between both models; again, the figure below illustrates this idea on an abstract level. While not required, feature distillation is typically used in combination with logits distillation.

Intuitively, feature distillation provides an even richer signal compared to (just) logit distillation as it enables a "deeper" knowledge transfer beyond outputs. On the other hand, it further adds complexity to training of the student model via distillation. Since the student model is typically much smaller than the teacher model — for example, having fewer layers or fewer neurons per layer — it is not obvious how to align both models and to calculate the feature distillation loss. For example, a teacher LLM might have 32 Transformer layers while the student LLM only has 8 Transformer layers. Here, a common approach is to align each Transformer layer of the student with every fourth layer of the teacher. If the aligned layers then also have different sizes, additional strategies (e.g., learnable projects or feature pooling) are required to enable the meaningful computation of a loss.

Low-Rank Approximation¶

Another common compression method utilizing that most LLMs or other very large models are over-parameterized is low-rank low-rank approximation (or low-rank decomposition). The fundamental idea is to approximate a weight matrix $\mathbf{W}^{m\times n}$ with smaller low-rank matrices, say, $\mathbf{A}^{m\times r}$ and $\mathbf{B}^{r\times n}$ such that $\mathbf{W} \approx \mathbf{A}\mathbf{B}$. Naturally, to yield a meaningful compression, $r$ is chosen to be smaller than $m$ and $n$, i.e., $r < min(m, n)$. In short, the goal of the decomposition is is that the new number of weights (represented by matrices $\mathbf{A}$ and $\mathbf{B}$) is smaller than the initial number of weights in matrix $\mathbf{W}$ — without (significantly) affecting the overall performance of the model.

To better illustrate this idea, let's consider a simple linear layer containing $10$ neurons and expecting an input of size $10$. When implemented, this linear layer features a weight matrix $\mathbf{W}^{10\times 10}$ looking as follows:

This means that the weight matrix of this linear layer contains $100$ trainable parameters in total. Now let's assume we found two matrices $\mathbf{A}^{m\times r}$ and $\mathbf{B}^{r\times n}$ such that $\mathbf{W} \approx \mathbf{A}\mathbf{B}$, and let's assume $r = 3$ — that is, we now have two matrices $\mathbf{A}^{10\times 3}$ and $\mathbf{B}^{3\times 10}$ whose product approximates $\mathbf{W}$. Again, let's quickly visualize both matrices.

Both new weight matrices $\mathbf{A}$ and $\mathbf{B}$ now contain $30$ values each; thus, a total of $60$ trainable weights — compared to initial number of $100$ weights in $\mathbf{W}$. More generalized, weight matrix $\mathbf{W}$ contains $mn$ values, matrices $\mathbf{A}$ and $\mathbf{B}$ contain together $(mr+rn)$ or $r(m+n)$ values. We can therefore evaluate the memory requirements for the model after the decomposition using the following ratio:

Notice, that $r$ may need to be noticeably smaller than $m$ and $n$ to actually gain an advantage. For example, if we set $r=8$ in the use above, matrices $\mathbf{A}$ and $\mathbf{B}$ would contain $80$ weights each, resulting in $160$ weights altogether, which are obviously more than the initial $100$ weights in $\mathbf{W}$.

So far, we assumed that we were given the two matrices $\mathbf{A}$ and $\mathbf{B}$ such $\mathbf{AB}$ is a good approximation of the initial weight matrix $\mathbf{W}$. Of course, the challenge in practice is to actually find (i.e., compute) $\mathbf{A}$ and $\mathbf{B}$. The well-known task of matrix decomposition (also known as matrix factorization is the process of breaking a large matrix into a product of smaller, simpler matrices that capture the essential structure or properties of the original. This is often done to simplify computations, reveal hidden patterns, or enable efficient storage and processing. In practical terms, it allows complex operations — such as solving systems of linear equations, computing matrix inverses, or applying transformations — to be performed more efficiently by working with the decomposed components. Various algorithms for matrix decomposition exits, and which can be applied for low-rank approximation; here is just a brief outline of popular approaches:

Singular Value Decomposition (SVD): SVD is one of the most fundamental and widely used low-rank approximation methods. It is particularly effective for compressing large, fully connected layers. SVD decomposes a matrix $\mathbf{W}^{m\times n}$ into three matrices $\mathbf{U}^{m\times m}$, $\mathbf{S}^{m\times n}$, and $\mathbf{V}^\top$ such that $\mathbf{W} \approx \mathbf{U}\mathbf{S}\mathbf{V}^\top$. Matrix $\mathbf{S}$ is a diagonal matrix containing the singular values in descending order. The singular values represent the "strength" or importance of each dimension along which the original matrix acts. The compression happens by keeping only the top $k$ singular values (and their corresponding vectors in $\mathbf{U}$ and $\mathbf{V}^\top$), giving is $\mathbf{W} \approx \mathbf{U}_k\mathbf{S}_k\mathbf{V}_k^\top$. Using our inital terminology $\mathbf{A} = \mathbf{U}_k\mathbf{S}_k$ and $\mathbf{B} = \mathbf{V}_k^\top$. SVD is often applied to individual layers in a trained network (post-training compression).

Tensor Decompositions: While SVD is a matrix decomposition technique, many modern neural network components, such as convolutional layers and attention mechanisms in LLMs, are better represented as higher-order tensors. Tensor decompositions generalize SVD to these multi-dimensional arrays, and there are various algorithms. For example, Canonical Polyadic (CP) decomposition is particularly effective for convolutional layers. Tucker decomposition (or Higher-Order SVD) is a more flexible and general technique than CP decomposition. It often results in a better trade-off between compression and accuracy. It's been applied to both convolutional and fully connected layers.

Non-Negative Matrix Factorization (NMF): In contrast to SVD, NMF directly decomposes a matrix $\mathbf{W}$ into two smaller matrices $\mathbf{A}$ and $\mathbf{B}$ such that $\mathbf{W} \approx \mathbf{AB}$. However, as the name suggestions, NMF requires that all values in $\mathbf{W}$ are non-negative (i.e., $\geq 0$) — the resulting values in $\mathbf{A}$ and $\mathbf{B}$ will also be non-negative. This constraint regarding non-negativity poses challenges for model compression since the weights in a typical neural network, including LLMs, are not constrained to be non-negative. However, there are cases where NMF can be applied. For example, some layers naturally feature non-negative data (e.g., some embedding layers or attention matrices). Also some regularization strategies during training "encourage" non-negative weights.

There are also other, often more specialized, matrix decomposition techniques. However, more deeper exploration is beyond the scope of this notebook.

Side note: The most basic use case for low-rank approximation to reduce the memory footprint of a model is to take a pretrained model and replace a selected subset or all weight matrices with (hopefully good) approximations. This new and smaller model is then used for inferencing. However, the decomposition into smaller matrices is still perfectly differentiable and such could be used for training. For example, after applying SVD on a pretrained model, the compressed network can then additionally be fine-tuned to recover any lost accuracy. In fact, the concept of low-rank approximations has also become a very popular fine-tuning strategy, as we will cover later.

Efficient Pretraining¶

Pretraining refers to the initial phase of training a neural network model — especially LLMs — on a massive, general-purpose dataset before it is fine-tuned for specific tasks. During pretraining, the model learns broad patterns in language (e.g., grammar, syntax, semantics, world knowledge) by predicting missing tokens, next tokens, or masked tokens from text. This is typically done in a self-supervised manner, meaning the training data does not need human labeling. Once pretrained, the model can be fine-tuned on much smaller, task-specific datasets (e.g., for translation, question answering, or summarization) with relatively little additional training. This two-phase approach allows the model to generalize well across a wide range of tasks and domains.

Particularly pretraining large foundation LLMs is exceedingly time and resource-intensive. As such, any means to make the training more efficient can translate to significant cost savings. In the following, we outline some of the current approaches to reduce the memory footprint and/or speed up the training of a model. In practice, different strategies are often combined to improve the overall training efficiency.

Mixed Precision Training¶

The fundamental motivation behind mixed precision training is similar to idea of quantization (see above) — that is, the representation of the model's trainable parameters using a low(er)-precision representation to reduce the size of the model in terms of the required memory but also to speed up computations In case of basic quantization — which is primarily done to make a pretrained model more efficient for inferencing — we now want to work with lower precision as part for the actual training. The main difference here is the overall memory footprint is now determined by:

- Model weights (effectively the description of the model)

- Activations (intermediate values needed for backpropagation)

- Gradients (calculated during backpropagation)

- Optimizer states (e.g. for Adam: momentum and variance estimates)

Using quantization to reduce the size of the memory only concerns the model weights, but for training, all those aspects regarding memory consumption are important.

For training neural network models, we generally require a high precision to ensure a stable training since the gradients and parameter updates may involve very small values. However, fp64 (double precision) is generally not needed because it offers far more numerical precision and range than required. Neural networks are inherently robust to small numerical errors due to their approximate nature and stochastic optimization (like gradient descent). While fp64 can represent values with very high precision (about 15-17 decimal digits), this level of detail does not meaningfully improve training outcomes. On the other hand, fp16 (half precision) is often insufficient on its own due to its limited precision (~3-4 decimal digits) and narrow dynamic range. These constraints can cause issues like gradient underflow, where small values round down to zero, or overflow, where large values exceed representable limits — both of which can destabilize training. This is why fp32 has become the standard precision for training neural networks.

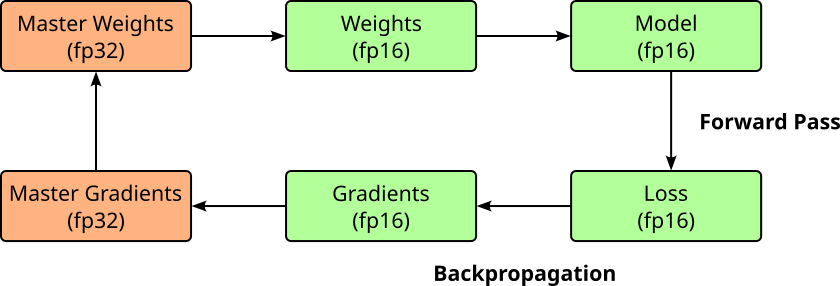

The idea of mixed precision training exploits the observation that performing some parts of the training fp16 precision does typically no harm a model's accuracy. In mixed precision training, key components of the model—such as weights, activations, and gradients — are stored and processed using fp16 to take advantage of its lower memory footprint and faster computation. However, because FP16 has limited precision and a smaller dynamic range, it can lead to instability or accuracy loss during training. To address this, a separate fp32 "master copy" of the model's weights is maintained. This FP32 copy is not used during the forward or backward passes but is crucial for accurate weight updates during the optimizer step, where it accumulates the gradients.

During each training iteration, a temporary fp16 version of the master weights is created and used for the forward and backward passes. This allows the training process to benefit from the reduced memory usage and faster throughput of FP16 computations. Meanwhile, the fp32 master ensures that numerical accuracy is preserved over time, especially during gradient accumulation and parameter updates. This hybrid strategy effectively reduces memory consumption and bandwidth demands while still maintaining training stability and final model accuracy. The figure below illustrates the overall training process using mixed precision. Notice that all calculations of the forward and backward pass (backpropgation) are down using fp16; only the actual update of the master weights are done using fp32.

Since all the computations — forward and backward pass — are done using fp16, it may not be obvious why having the fp32 master copy of the weights is actually needed. This has two main reasons. For one, while fp16 is often sufficient to represent the gradients with sufficient precision, the gradients are first multiplied with the learning before performing the parameter updates. Since training LLMs commonly involve learning rates around $0.0001$ or $0.00005$, fp16 is often insufficient to appropriately represent the product. Secondly, in practice, a weight value is much larger than the weight update, adding both in fp16 can cause the update to effectively vanish. This happens because fp16 has limited precision (only 10 bits in the mantissa). If the weight is more than 2048 times larger than the update, the update gets right-shifted too much during addition, possibly to the point where it becomes zero. To avoid this, updates are typically computed and accumulated in fp32, which has much higher precision and range.

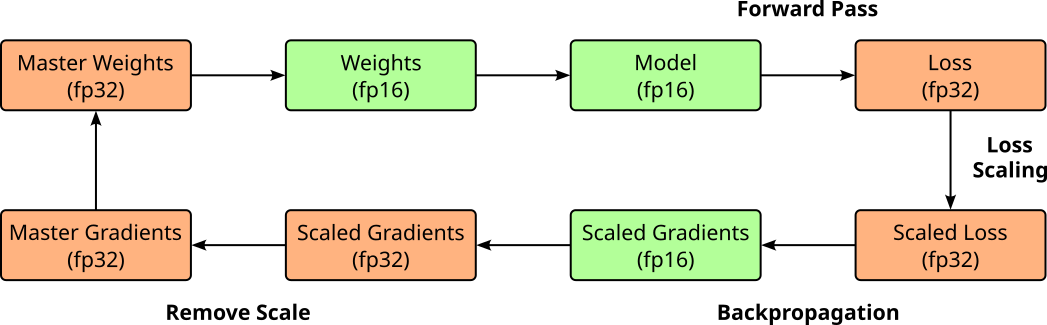

Although fp16 is often sufficient to store the gradients (i.e., before the multiplication with the learning rate), the gradients can become very small so that they will underflow and be treated as zero. This means no meaningful update happens for the affected parameters. The common approach to address this issue is called loss scaling. In loss scaling, the loss value is first multiplied by a scaling factor — often using a constant factor such as 128 or 1024 — before backpropagation begins. This boosts the magnitude of the resulting gradients, helping ensure they stay within the representable range of FP16 and do not underflow to zero. After the gradients are computed, the same scaling factor is divided out just before the optimizer step, ensuring that the final weight updates remain mathematically correct. The figure below shows the extended process of mixed precision training with loss scaling.

Mixed precision training has been shown to significantly improve training performance for large models, including large language models (LLMs), by reducing memory usage and increasing computational throughput. By performing most operations in FP16 while maintaining critical values like weight updates in fp32, it enables faster training on modern hardware — particularly GPUs with specialized support for half-precision arithmetic. Despite the reduced precision, mixed precision training achieves comparable accuracy to full fp32 training in practice. Techniques like loss scaling help preserve numerical stability, ensuring that model quality is not compromised. As a result, mixed precision has become a standard approach for efficiently training state-of-the-art neural networks at scale.

Scaling Models¶

The idea of scaling large models such as LLMs from smaller models is to train progressively larger architectures by leveraging insights, weights, or design patterns learned from smaller versions. Instead of starting from scratch with a massive model, researchers often begin with a smaller, computationally cheaper model to experiment with hyperparameters, architectures, optimization strategies, and training data. Once these settings are tuned, the same or similar configurations are applied to progressively larger models. This strategy is particularly valuable for LLMs because training from scratch at extreme scale is expensive and risky. Starting small allows researchers to identify bottlenecks like gradient instability or underfitting before committing millions of GPU-hours. It also provides a smoother pathway to frontier-scale performance while controlling costs and avoiding catastrophic training failures that would be far more costly with a massive model.

"Reverse" Model Compression Strategies.¶

We saw that model compression aims to convert a complex model into a smaller and/or simpler one to reduce the memory footprint and speed up inference time, without sacrificing the model's accuracy (too much). Some of these strategies can be "flipped" and used to scale up smaller/simpler models into more complex models with more capacity.

Low-Rank Approximation. If we assume that $\mathbf{W}^{m\times n}$ will be some weight matrix in our final model, we can first replace $\mathbf{W}$ with the product $\mathbf{AB}$ of two smaller matrices $\mathbf{A}^{m\times r}$ and $\mathbf{B}^{r\times n}$ — with $r$ being (much) smaller than $m$ and $n$ — during the early stage of the training. Then, we reconstruct $\mathbf{W}$ by calculating $\mathbf{W} = \mathbf{AB}$ and continue training using the full matrix $\mathbf{W}$. The assumption again is that the low-rank approximation of $\mathbf{W}$ — which is faster to train since the number of weights is much smaller — will be very close to the final matrix $\mathbf{W}$, so only little late-stage training with the full matrix is needed.

Knowledge Inheritance. The idea of knowledge inheritance is similar to knowledge distillation (see above), but with the difference that the smaller pretrained model acts as the teacher, and the student is the new, larger model we want to train. Since we assume that the student model will at some point surpass the accuracy of the teacher model, the impact of the teacher model needs to decrease during training — for example, but decreasing the weight of the logits distillation loss over time.

Model Growth for Progressive Training.¶

The basic idea behind using model growth for progressive training is to build and train a large neural network incrementally. Instead of training a massive model from scratch, you begin with a smaller, more manageable network. Once this smaller network is sufficiently trained, you expand it by adding new layers or modules (more depth), or by increasing layers (more width). The weights from the smaller, pretrained model are used to initialize the corresponding layers in the new, larger network. By starting small, you can use less computational power and memory, and the training process is more stable. The pretrained weights from the smaller model act as an excellent starting point for the larger one, helping to avoid the problematic "cold start" of randomly initialized weights. This process is repeated, gradually increasing the model's size and complexity, with each new iteration benefiting from the knowledge learned in the previous, smaller stage — hence, progressive training.

Basically all popular modern LLMs rely on the Transformer architecture. As quick recap, the main parameters of the Transformer architecture the determine the size of a model in terms of its required memory — and with that also the required training — are:

- Number of layers $n_{layers}$: the number of Transformer blocks or encoder/decoder layers

- Number of attention heads $n_{heads}$: the number of attention heads in each multi-head attention layer

- Hidden size or model dimension $d_{model}$: the size of the embedding vectors and the main hidden representation in the model

- Feed-forward network (FFN) dimension $d_{ffn}$: the size of the intermediate layer in the position-wise feed-forward network

To give some examples, the table below shows the values for the popular models of the GPT family. Note that at the time of writing, OpenAI has not released the numbers for its more recent and larger models. Still the main take-away message is that more complex and thus more capable models are essentially just scaled-up versions of simpler models (ignoring changes to the training data).

| Model | $n_{layers}$ | $n_{heads}$ | $d_{model}$ | $d_{\text{\textit{ffn}}}$ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPT-1 | 12 | 12 | 768 | 3,072 |

| GPT-2 Small | 12 | 12 | 768 | 3,072 |

| GPT-2 Medium | 24 | 16 | 1024 | 4,096 |

| GPT-2 Large | 36 | 20 | 1280 | 5,120 |

| GPT-2 XL | 48 | 25 | 1600 | 6,400 |

| GPT-3 125M (Ada) | 12 | 12 | 768 | 3,072 |

| GPT-3 350M (Babbage) | 24 | 16 | 1024 | 4,096 |

| GPT-3 760M (Curie) | 24 | 16 | 1536 | 6,144 |

| GPT-3 1.3B (Babbage-002) | 24 | 24 | 2048 | 8,192 |

| GPT-3 2.7B | 32 | 32 | 2560 | 10,240 |

| GPT-3 6.7B | 32 | 32 | 4096 | 16,384 |

| GPT-3 13B | 40 | 40 | 5120 | 20,480 |

| GPT-3 175B (Davinci) | 96 | 96 | 12288 | 49,152 |

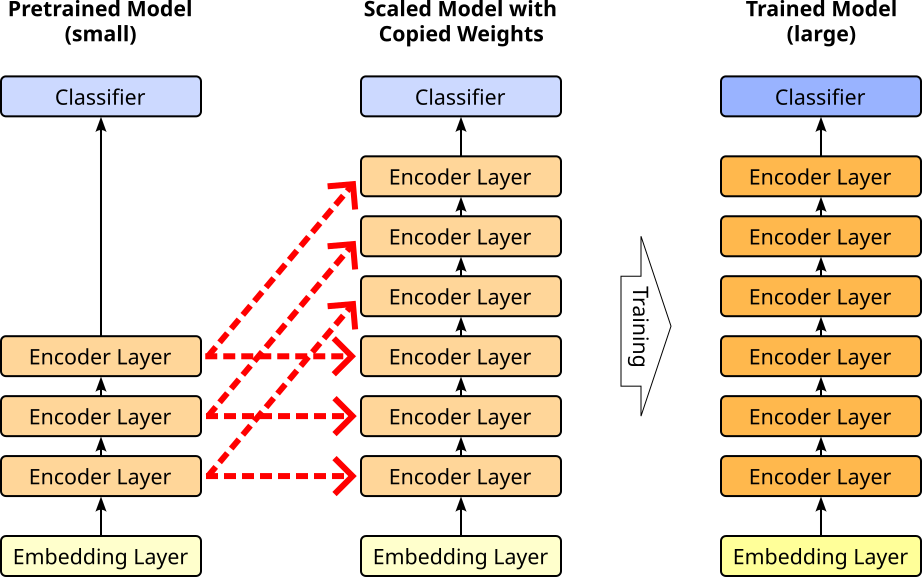

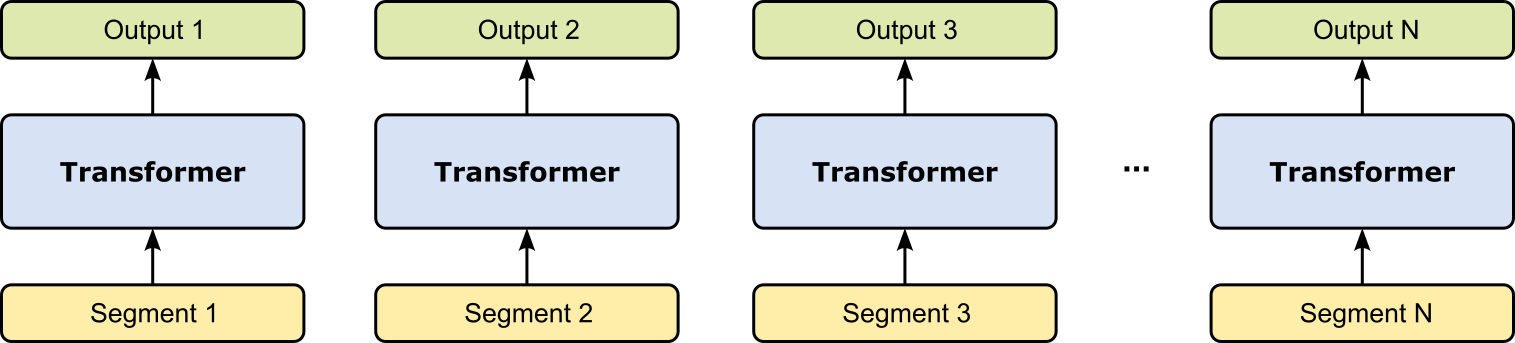

A wider range of strategies have been proposed to take a small(er) pretrained model and scale it up by increasing any subset of $n_{layers}$, $n_{heads}$, and $d_{model}$, $d_{\text{\textit{ffn}}}$ and use the available weights from pretrained model to kick-start the training of the now larger model in smart way. Just give one example for the Transformer architecture here, an approach proposed early on is to increase the number of layers $n_{layers}$ and simply copy over the weights from lower layers — also called stacking. This approach relies on the observation that the weights across all layers in a pretrained model often show a similar distribution. Thus, the weights of a lower layer make a good initialization of a higher layer. The figure below illustrates the idea of stacking using a Transformer encoder for a BERT model.

In this example, we start with a small pretrained model containing 3 encoder layers. We then create the larger model by duplicating the 3 encoder layers to now have 6 encoder layers in total. The red arrows indicate the weights from which the pretrained layer get copied to the newly added layer; of course, the weights of the embedding and classifier layer get also directly copied over. The larger model is then trained as a whole which includes updates of all weights across all layers. After the training, this process can be repeated by again duplicating the encoder layers, copying over the weights, and training the new model. The assumption/expectation is that the copied weights serves as a good initialization of the newly added layers to speed up the training process of the scaled model.

Various strategies for model growth in progressive training exist, aiming to build large, high-performing models by starting with smaller, more manageable ones and gradually expanding their capacity. Beyond adding more layers as shown in the example, other common approaches include widening existing layers, increasing the number of attention heads, or expanding hidden dimensions over time. Some methods also involve progressively growing the vocabulary or embedding sizes, or gradually unfreezing parameters that were initially fixed. However, most model growth strategies rely on specific assumptions and require careful design to work effectively. For instance, they often assume that the knowledge learned in the smaller model will transfer well to the expanded architecture without significant degradation, and that the optimizer and learning rate schedule can handle the sudden increase in parameters. Decisions such as when and how to grow the model, how to initialize new parameters, and how to avoid catastrophic forgetting or instability are crucial. Without careful consideration of these factors, progressive training can lead to inefficient scaling, unstable convergence, or suboptimal performance compared to training the full model from scratch.

Initialization Techniques¶

Weight initialization plays a critical role in the training of neural networks, especially large models such as LLMs, because it directly affects how signals propagate through the network during both the forward and backward passes. If the initial weights are too small, activations can vanish as they pass through many layers, leading to very small gradients and slow or stalled learning (vanishing gradients). Conversely, if the weights are too large, activations and gradients can explode, causing instability and divergence during training. Proper initialization helps maintain a stable variance of activations and gradients across layers, ensuring that the learning signal remains strong from the input to the output and back again. For large language models, the sheer depth and parameter count amplify any issues caused by poor initialization. In such architectures, small imbalances in early layers can compound exponentially, leading to numerical instability, gradient collapse, or even complete training failure.

For very large architectures like LLMs, initialization strategies are chosen with extreme care to keep activations and gradients stable across hundreds of layers and billions of parameters. Some common approaches include:

Xavier / Glorot Initialization is designed for $\text{tanh}$ or $\text{sigmoid}$ activations, Xavier initialization scales weights based on the number of input and output units ($\text{\textit{fan}}_{in}$ and $\text{\textit{fan}}_{out}$) so that the variance of activations is preserved. While it’s less common for modern transformers that use ReLU or GELU, it remains a foundation for understanding scaling principles.

Kaiming (He) Initialization is optimized for ReLU-type activations, this method scales by $\sqrt{2/\text{\textit{fan}}_{in}}$ to prevent the shrinking of signal variance as it moves forward. Some transformer feed-forward layers use a Kaiming-like initialization to match their activation functions.

Normalized Initialization with Dimension-Based Scaling: In transformers, weights (especially in attention projections) are often initialized from a normal distribution with variance inversely proportional to the hidden dimension. For example, attention logits are scaled by $1/d_k$ — where $d_k$ is the hidden dimension of an attention head — to prevent large values that could saturate the softmax, and some initializations multiply weight standard deviation by $1/n_{layers}$ to avoid residual stream blow-up in deep stacks.

DeepNorm / μParam Scaling: Newer LLM training strategies modify initialization together with residual connection scaling to keep both forward activations and backward gradients stable in very deep networks. For example, DeepNorm scales residual branches by constants like $\alpha = (2N)^{0.25}$, where $N$ is the number of layers. μParam scaling adjusts weight initialization so model capacity grows without destabilizing gradient magnitudes.

In practice, LLM training often combines these methods—using variance-preserving Gaussian initializations with careful per-layer scaling, orthogonal setups for stability, and explicit normalization (LayerNorm or RMSNorm) to continually re-stabilize the signal throughout the network. Without these refinements, models like GPT or PaLM could suffer severe instability long before convergence.

Training Optimizers¶

Optimizers are algorithms that adjust the parameters (weights and biases) of a neural network during training to minimize a loss function. They determine how the model learns from the data by deciding the size and direction of each parameter update based on the computed gradients from backpropagation. The optimizer's role is crucial because the way it navigates the high-dimensional loss landscape directly affects training speed, stability, and the final model quality. The purpose of an optimizer is to find parameter values that produce accurate predictions while using computational and memory resources efficiently.

Basic optimizers like Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) update parameters using the raw gradient information, while more advanced ones — such as Adam, AdamW, Adafactor, and Lion — adapt the learning rate for each parameter based on historical gradient information. This adaptation helps deal with challenges like noisy gradients, ill-conditioned optimization surfaces, and varying gradient magnitudes across layers. In large models such as LLMs, optimizers must also address scale-related challenges: keeping training numerically stable across billions of parameters, reducing the risk of exploding or vanishing gradients, and managing memory overhead. The following table lists some popular optimizer algorithms and their (potential) limitations for training LLMs.

| Optimizer | Why It's Used | Limitations for LLMs |

|---|---|---|

| SGD (with or without momentum) | Simple, memory-efficient, and reliable for well-conditioned problems. Works well when combined with momentum and learning rate schedules. | Converges slowly in high-dimensional, non-convex spaces; very sensitive to learning rate choice; requires more tuning and warmup. |

| Adam / AdamW | Adaptive learning rates per parameter; fast convergence; robust to gradient scaling. AdamW decouples weight decay from momentum. | 2-3x memory usage due to first and second moment states; hyperparameter sensitivity; can still diverge without proper init/normalization. |

| Adafactor | Memory-efficient alternative to Adam (factorized second-moment storage); used in T5 and other huge models. | Less stable in small-batch or fine-tuning; needs careful learning rate warmup and gradient clipping. |

| Lion (Evolved Sign Momentum) | Lower memory than Adam (stores only momentum); competitive performance on LLMs; efficient update rule. | Relatively new; limited large-scale production use; hyperparameter tuning can be sensitive. |

In short, common optimizers trade off memory requirements with stability when it comes to training very large networks. Training LLMs efficiently requires specialized optimizers because their massive scale — often billions or trillions of parameters — pushes standard methods to their limits. Common algorithms like vanilla SGD may converge too slowly in such high-dimensional spaces, while adaptive methods like Adam triple memory usage due to extra parameter states. At this scale, inefficiencies in computation or communication quickly multiply, making training both costly and slow. Beyond memory concerns, large models have highly varied gradient magnitudes across layers, and without adaptive scaling, training can become unstable or diverge. Deep architectures like transformers also introduce risks such as exploding attention scores and residual growth, demanding optimizers that work hand-in-hand with careful initialization, normalization, and mixed-precision stability.

System-Level Pretraining Efficiency Optimization¶

In simple terms, training a neural network comes down to performing many matrix and vector operations. This means that almost all the computations involved — both in the forward pass (making predictions) and the backward pass (computing gradients) — can be expressed as linear algebra. Inputs, weights, and activations are represented as vectors and matrices, and the core operations are matrix multiplications, additions, and element-wise functions. For example, in each layer, the network computes $\mathbf{y} = \mathbf{W}\mathbf{x} + \mathbf{b}$ to transform the data, and during backpropagation it uses similar matrix operations to calculate weight updates.

This mathematical structure is why hardware like GPUs, which excel at parallel linear algebra, can train neural networks so efficiently. GPUs contain thousands of cores designed to execute these operations in parallel, significantly speeding up training compared to CPUs, which have far fewer cores optimized for sequential processing. This parallelism allows GPUs to process large batches of data and compute gradients for many parameters at once, reducing training time from weeks to days or even hours. For very large models such as LLMs, the sheer scale of parameters and computations makes GPU acceleration not just advantageous but practically mandatory. These models can have hundreds of billions of parameters, requiring enormous memory bandwidth and compute throughput to train efficiently.

LLMs and other networks have become so large that training them on a single GPU — that is, a single piece of hardware containing all cores and memory — is no longer feasible but requires large computing clusters with multi-GPU setups. Training LLMs on large GPU clusters introduces challenges in communication, synchronization, and workload distribution. This requires frequent exchange of large amounts of data — such as gradients, parameters, or activations — between GPUs, often across different machines. Even with high-speed interconnects like NVLink or InfiniBand, communication overhead can become a bottleneck, reducing the theoretical scaling efficiency. Synchronization delays also arise because all GPUs must stay in step during training; if one GPU is slower (e.g., due to uneven workload), it can stall the entire system. Another challenge is fault tolerance and system stability at scale. Large clusters have thousands of GPUs running for days or weeks, so hardware failures, network issues, and software bugs are inevitable. Memory management is also a concern—storing massive models, optimizer states, and activation buffers requires careful sharding and offloading to prevent GPU memory overflow.

Efficiently training LLMs in GPU clusters relies on a combination of parallelization strategies, memory optimizations, and advanced scheduling techniques to maximize throughput while minimizing communication overhead. The most common strategies include data parallelism (replicating the model across GPUs and splitting the training data), tensor/model parallelism (splitting large layers across GPUs so that each GPU handles part of the computation), and pipeline parallelism (breaking the model into stages that process different microbatches in sequence). Frameworks like Megatron-LM and DeepSpeed often combine these into 3D parallelism, which integrates all three to scale across thousands of GPUs.

Advanced methods focus on reducing the communication and memory costs of these strategies. ZeRO (Zero Redundancy Optimizer) partitions optimizer states, gradients, and parameters across devices to avoid storing full copies on each GPU. Activation checkpointing trades extra computation for lower memory usage by recomputing activations instead of storing them. Mixed precision training (see above) speeds up computation and reduces memory footprint without significant accuracy loss. More recent approaches include sequence parallelism (splitting sequences across GPUs for long-context models), gradient compression (quantizing or sparsifying gradients before communication), and asynchronous communication to hide latency. Together, these methods allow LLM training to scale to hundreds of billions of parameters without being bottlenecked by GPU memory or interconnect bandwidth.

Efficient Fine-Tuning¶

The purpose of fine-tuning large pretrained LLMs is to adapt their broad, general knowledge to perform well on a specific task, domain, or style. While pretraining equips the model with strong language understanding and general knowledge, it does not guarantee optimal performance in specialized contexts — such as legal analysis, medical text processing, or technical customer support. Fine-tuning refines the model's responses using targeted data so it can use domain-specific terminology correctly, follow specialized reasoning patterns, and align with desired output formats or tones. Fine-tuning is needed because training a large model from scratch is prohibitively expensive in terms of data, computation, and engineering effort. By leveraging the general-purpose abilities gained during pretraining, fine-tuning can achieve high accuracy and domain relevance with far less cost and data. It also ensures that models remain up to date with evolving knowledge, regulations, or user needs, making them more reliable and useful in real-world applications.

However, fine-tuning LLMs also comes with several challenges, both technical and practical. A key issue is catastrophic forgetting, where the model loses some of its general capabilities or pretraining knowledge when overfitted to the fine-tuning dataset. This can make the model perform worse on tasks outside the fine-tuned domain. Closely related is overfitting, which occurs when the fine-tuning data is too small or too narrow, leading the model to memorize rather than generalize — producing brittle, biased, or repetitive responses. More generally, specialization with general usefulness is non-trivial: too much fine-tuning can narrow the model’s capabilities, while too little may fail to achieve the desired performance improvements. Lastly, fine-tuning large models still requires substantial computational resources — even if it is far cheaper than training from scratch, the process still demands powerful GPUs, careful hyperparameter tuning, and memory-efficient techniques to handle billions of parameters.

Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning¶

Parameter-efficient fine-tuning (PEFT) is an approach to adapting large pretrained models, such as LLMs, by updating only a small subset of their parameters instead of all of them. Traditional fine-tuning requires modifying every parameter in the model, which is computationally expensive and storage-heavy, especially for models with billions of parameters. PEFT methods, like LoRA (Low-Rank Adaptation), adapters, or prefix-tuning, inject small trainable modules into the network or adjust low-rank projections, allowing the core pretrained weights to remain frozen. This significantly reduces the number of trainable parameters while still achieving strong task-specific performance. PEFT has two key advantages:

Efficiency: Fine-tuning a full LLM can require hundreds of gigabytes of GPU memory, long training times, and high storage costs for each specialized version of the model. In contrast, PEFT methods require far fewer resources, making it feasible to train and store many domain-specific adaptations from a single base model. This is especially valuable when an organization needs multiple specialized variants without duplicating the entire LLM for each case.

Flexibility and maintainability:. Since PEFT keeps the base model intact, it is easy to swap in or combine different fine-tuned modules, update them independently, or revert to the original general-purpose model when needed. This modularity also enables faster experimentation and safer deployment, as the risk of degrading the base model's broad capabilities is minimized (e.g., catastrophic forgetting).

The core assumption behind PEFT is again that large models such as LLMs are often over-parameterized and that the changes needed to adapt such a model to a new task often lie in a low-dimensional subspace. By only training a small/reduced set of parameters, PEFT strategies often achieve nearly the same performance as full fine-tuning while requiring far less memory, computation, and storage. In short, PEFT makes fine-tuning large models practical, cost-effective, and scalable while retaining most of the performance benefits of full fine-tuning. Let's go over some of the common approaches for parameter-efficient fine-tuning.

Low-Rank Adaption (LoRA)¶

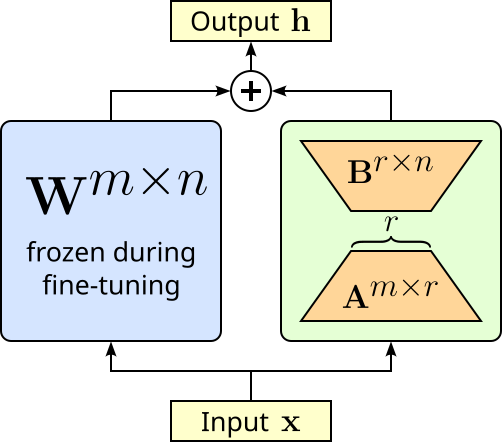

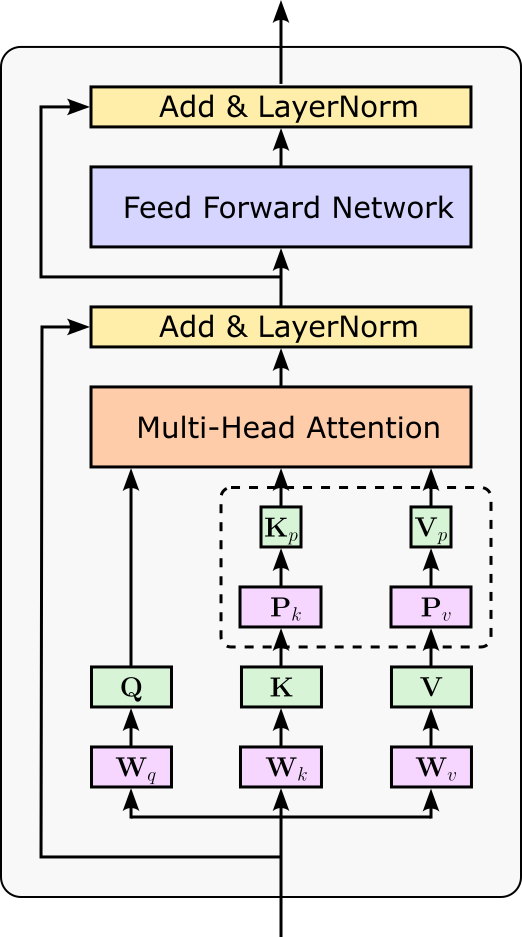

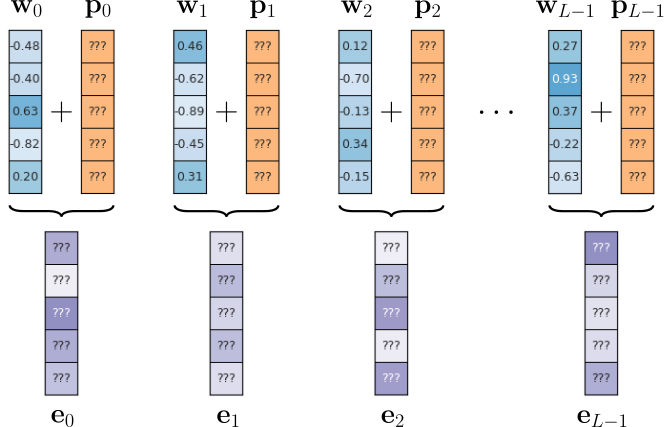

As the name suggests, LoRA is closely related to low-rank approximation of model compression. LoRA adapts large pretrained models by adding small, trainable low-rank matrices to certain weight matrices &mdashl; typically in the attention and feed-forward layers — while keeping the original weights frozen. Instead of updating the full weight matrix $\mathbf{W}^{m\times n}$ (which can be very large), LoRA learns two much smaller matrices $\mathbf{A}^{m\times r}$ and $\mathbf{B}^{r\times n}$ whose product approximates the necessary update $\Delta \mathbf{W} = \mathbf{AB}$, which then yields the final output of the layer $\mathbf{h} = \mathbf{W} + \Delta\mathbf{W}$. The matrices $\mathbf{A}$ and $\mathbf{B}$ have dimensions chosen so that the rank $r$ is much smaller than the original matrix size, drastically reducing the number of trainable parameters. The figure below illustrates the idea of LoRA.

Matrix $\mathbf{A}$ is typically initialized with some random Gaussian noise,i.e., $\mathbf{A} \sim \mathcal{N}(0, \sigma^2)$), while matrix $\mathbf{B}$ is initialized with all elements being $0$, i.e., $\mathbf{B} = 0$. This means that at the beginning of the fine-tuning $\Delta\mathbf{W} = 0$ so that the output of the layer is only determined by the original weight matrix $\mathbf{W}$. Of course, during the fine-tuning, matrices $\mathbf{A}$ and $\mathbf{B}$ will get updated during backpropagation so that $\Delta\mathbf{W} \neq 0$.

Adapter-based Tuning¶

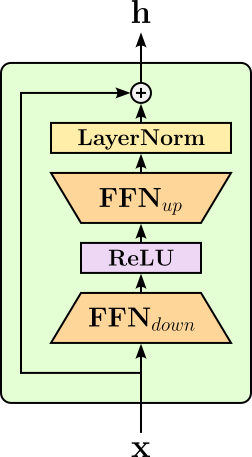

In general, adapters are small, trainable neural network modules inserted into the layers of a large pretrained model to enable task-specific adaptation without modifying the original model's parameters. During fine-tuning, only the adapter parameters are updated, while the vast majority of the model's weights remain frozen. Typically, an adapter is a bottleneck layer that projects the high-dimensional hidden states of the model down to a smaller dimension, applies a nonlinearity, and then projects them back up to the original dimension before passing them to the next layer. This allows the adapter to learn compact task-specific transformations while keeping the base model intact. The figure below shows a simple adapter in the form of a bottleneck layer.

Here, the first fully connected network (FFN) layer maps the input down into a lower-dimensional representation. After applying a non-linear activation function, a second FFN layer maps the activation back up into the same dimension of the input. The example above also performs layer normalization (LN) at the end — while the adapters can be arbitrarily complex, simple modules as shown here are very common. Adapters also have a residual connection so they can adjust the pretrained model's representations without overwriting them, preserving the general knowledge learned during pretraining while adding small, task-specific refinements. This design also helps with stable training as the output starts as identical to the pretrained hidden state, the fine-tuning process can gradually incorporate task-specific modifications instead of making abrupt changes to the model's internal representations.

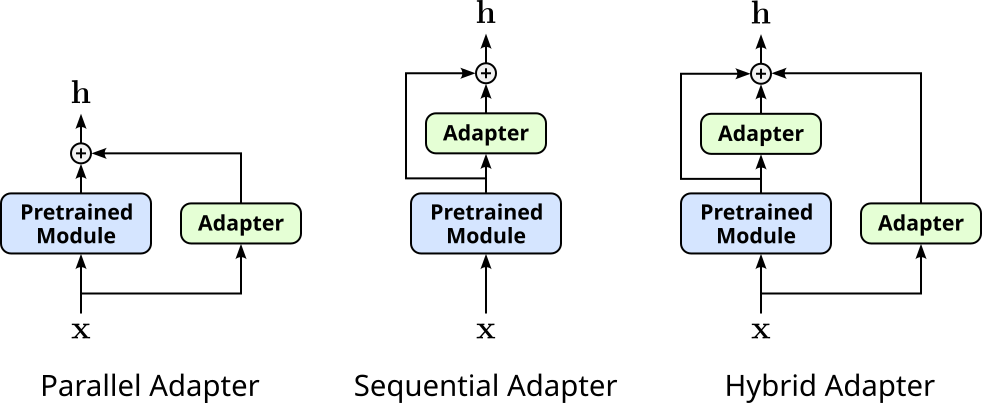

Adapters can then be inserted into a pretrained model parallel to existing layers, sequentially (i.e., between existing layers), or both (hybrid). The following figure illustrates the basic setup for all three alternatives.

You may notice that parallel adapters are very similar to LoRA, and in some sense they are closely related. However, adapters are complete modules (i.e., small sub networks with linear layers, activation functions, normalization layers, etc.) and are inserted parallel to complete modules of the pretrained model. In contrast, LoRA "only" inserts low-rank approximations parallel to a single weight matrix, typically of a single linear layer.

Prompt Tuning¶

Although LLMs (e.g., GPT, LLaMA) are trained to "simply" predict the next token given a current sequence of tokens, both the training datasets and the models' capacities are so large that the models shows emergent capabilities — that is, LLMs can perform tasks they have not been explicitly trained for. Training on massive text corpora to predict the next token forces the model to learn deep patterns about language, knowledge, facts, reasoning chains, and even some world understanding, all embedded implicitly in the data. Even without explicit supervised task labels — such as input-target pairs for machine translation, question-answer pairs — the model sees tons of diverse text during training, including, for example:

- Translations embedded in parallel corpora or multilingual texts.

- Instructions and question-answer pairs.

- Code snippets, stories, dialogues.

This is why, with the "right prompt", we can ask a pretrained LLM to, say, translate a sentence from English to German. However, there are arbitrary ways to prompt the LLM and not all ways may yield satisfactory results. For example, here are some very basic prompts we might use to get the translation of an English sentence:

- "Translate English to German: Hello, how are you?"

- "English: Hello, how are you? German:"

- "Translate this to German: Hello, how are you?"

- "What is 'Hello, how are you?' in German?"

While for humans the intention of all four alternatives is clearly the same, it is not obvious if this is also true for the LLM, or if one alternative might perform better than the others. The questions is therefore: For a given task — here: English-to-German translation — can we learn the best prompt. Of course, tokens themselves are discrete values and backpropagation requires gradients, which are continuous and differentiable signals used to update parameters. However, recall that the first step of an LLM is to convert tokens into continuous embedding vectors, which can be learned via backpropagation. And this is where prompt tuning comes into play.

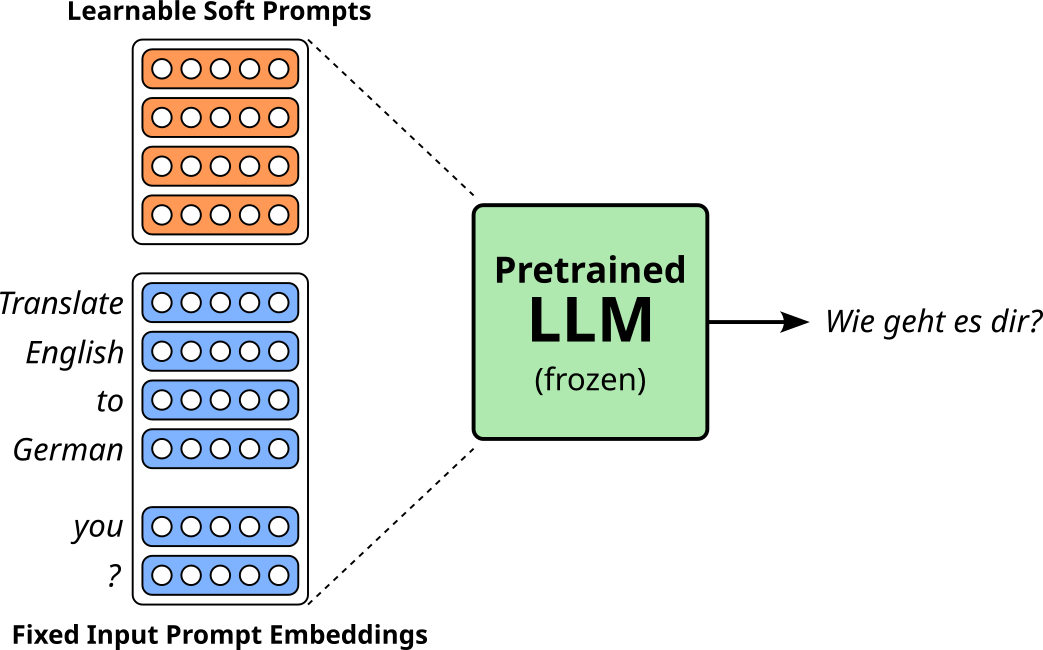

After converting an user prompt into its corresponding sequence of embedding vectors, prompt tuning prepends a fixed number of additional embedding vectors to this sequence. At the beginning (before the training), these additional embedding vectors are randomly initialized. This final sequence of vectors is then given to the pretrained LLM during training. The important detail is that after backpropagation only the additional embedding vectors are updated — all parameters of the pretrained LLM (incl. in the embedding layer) remain unchanged. The figure below illustrates this idea assuming a encoder-decoder LLM fine-tuned for an English-to-German machine translation task assuming "Translate English to German: Hello, how are you?" as input prompt (and "Wie geht es dir?" being the German translation).

In this example, to keep it simple, we only add 4 embedding vectors to the initial sequence of vectors from the pretrained embedding layer; and only those 4 vectors are getting updated during training. Since these additional vectors are treated by the LLM as additional words/tokens, but do not represent actual words/tokens, these added embedding vectors are also called soft prompts (compared to actual text prompts considered hard prompts) — you could find the tokens in your vocabulary with embedding vectors closest to the soft prompt vectors, but there is no expectation that the tokens are in any way meaningful.

The obvious advantage of prompt tuning is, of course, the number of parameters that we train is very small. All parameters (weights, biases, etc.) of pretrained LMM are frozen and do not get updated after backpropagation. This also means that prompt tuning does not negatively affect the overall capabilities of the LLM to generate well-formed text. Another benefit is modularity since different soft prompts can be swapped in and out for different tasks without retraining the model itself. For example, besides our learned soft prompt for English-to-German machine translation, we might also have learned soft prompts for sentiment analysis, document summarization, or question answering.

However, prompt tuning also has limitations. Since it does not alter the internal weights of the model, it relies entirely on the model's existing knowledge and representational space. In simple terms, this means that the pretrained model is already capable of solving the specific tasks, but benefits from the additional "guidance" provided by the learned soft prompts. Thus, the model may underperform compared to full fine-tuning on tasks that require significant adaptation or domain-specific knowledge the model has not already learned. This also implies that soft tuning often works best for very large models; smaller models may not benefit as much because their representations are less rich and flexible. Prompt tuning can also be sensitive to the initialization of the soft prompts, and in low-resource settings, it may converge more slowly or get stuck in suboptimal solutions.

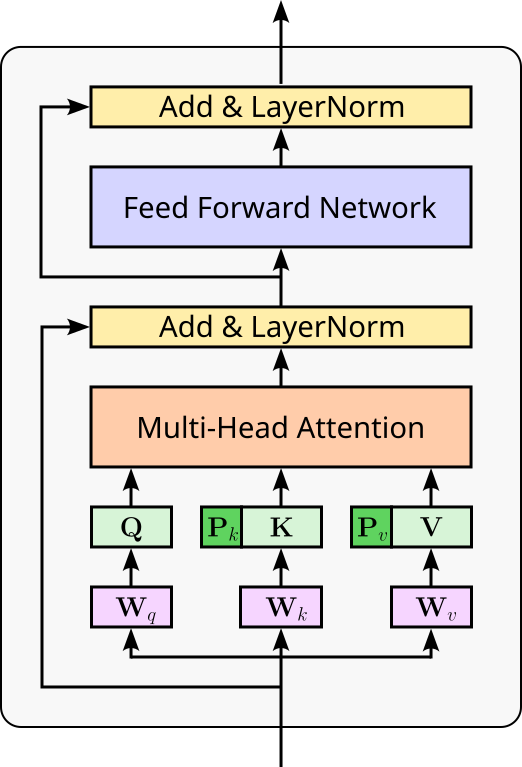

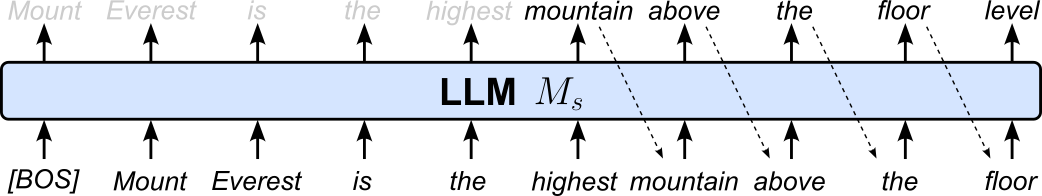

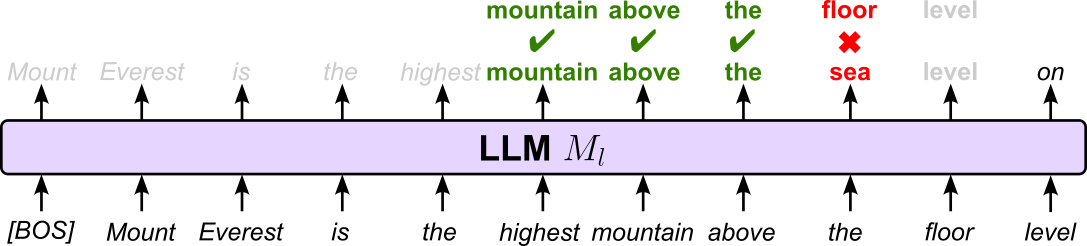

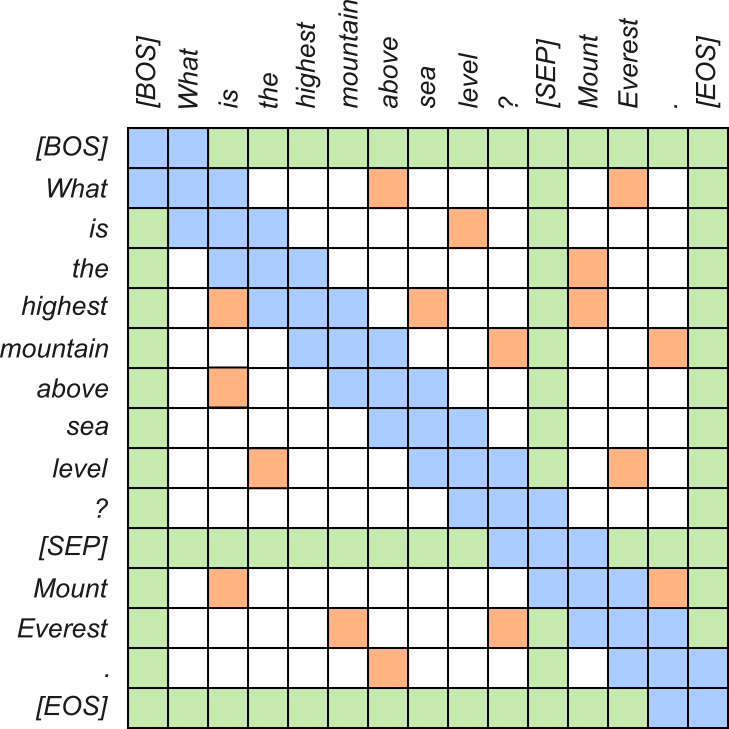

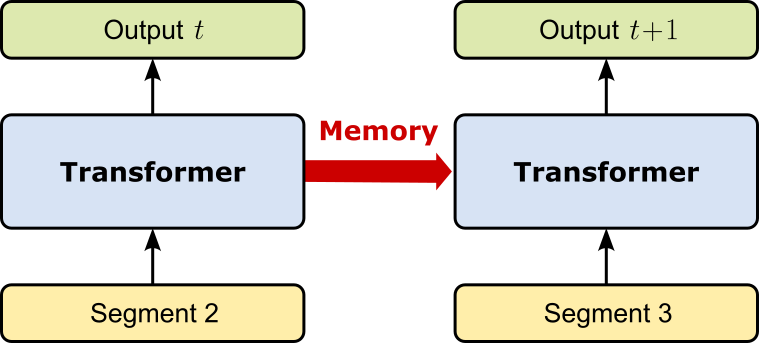

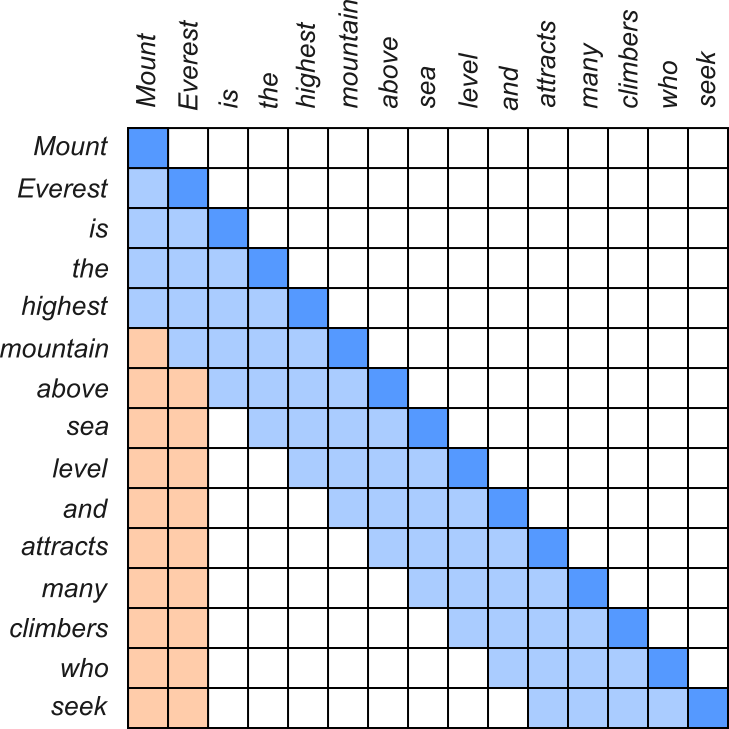

Prefix Tuning¶