Disclaimer: This Jupyter Notebook contains content generated with the assistance of AI. While every effort has been made to review and validate the outputs, users should independently verify critical information before relying on it. The SELENE notebook repository is constantly evolving. We recommend downloading or pulling the latest version of this notebook from Github.

Data Preparation for Training LLMs — An Overview¶

Data preparation is a foundational step in training large language models (LLMs), playing a critical role in determining the quality, safety, and performance of the resulting model. These models learn patterns and information from vast text datasets, so the accuracy, diversity, and cleanliness of that data directly influence their capabilities. Unlike traditional machine learning tasks, where curated datasets are often small and well-defined, LLMs require enormous volumes of heterogeneous data pulled from various domains and sources. This makes data preparation a large-scale, complex process that demands careful planning and execution.

The preparation pipeline typically begins with data collection, where text is gathered from sources like websites, books, academic publications, forums, and other digital content repositories. Once collected, the data must be converted into a consistent format, ensuring compatibility with tokenization systems and model training frameworks. This often involves converting files from HTML, PDF, or DOC formats into plain text or structured JSON representations. Following this, deduplication is essential to remove redundant content, which helps reduce training bias, prevents overfitting, and saves computational resources. Additional cleaning steps include removing boilerplate content (e.g., ads, navigation menus), filtering low-quality or irrelevant text, and normalizing Unicode characters to ensure consistency.

One of the main challenges in this process lies in balancing scale and quality. Given the sheer volume of data, it’s not feasible to manually inspect all content, so automated tools and heuristics must be used—yet these are prone to false positives and negatives. Language diversity, formatting inconsistency, and domain variability further complicate the task. Additionally, model training requires data to be tokenized and structured into sequences of manageable length, introducing further complexity in ensuring contextual coherence and content coverage.

Beyond the technical challenges, ethical considerations are crucial. Training data must be vetted for harmful, biased, or private content, as LLMs can memorize and regurgitate sensitive or toxic material if not carefully filtered. This includes avoiding personal data, respecting copyright laws, and mitigating the propagation of social biases found in online text. Transparency in the data sources used and the filtering methods applied is increasingly seen as a best practice to foster trust and accountability in AI development.

Setting up the Notebook¶

Make Required Imports¶

This notebook requires the import of different Python packages but also additional Python modules that are part of the repository. If a package is missing, use your preferred package manager (e.g., conda or pip) to install it. If the code cell below runs with any errors, all required packages and modules have successfully been imported.

from src.utils.libimports.llmdataprep import *

from src.utils.data.files import *

Download Required Data¶

Some code examples in this notebook use data that first need to be downloaded by running the code cell below. If this code cell throws any error, please check the configuration file config.yaml if the URL for downloading datasets is up to date and matches the one on Github. If not, simply download or pull the latest version from Github.

example_pdf, _ = download_dataset("text/docs/llm-example-document.pdf")

example_docx, _ = download_dataset("text/docs/llm-example-document.docx")

File 'data/datasets/text/docs/llm-example-document.pdf' already exists (use 'overwrite=True' to overwrite it). File 'data/datasets/text/docs/llm-example-document.docx' already exists (use 'overwrite=True' to overwrite it).

Preliminaries¶

The purpose of this notebook is to provide an overview to common steps and challenges when collecting and preparing a dataset for training LLMs. In practice, this process often requires a lot of customization and tweaks depending on the specific task. This also means that there is not simple check list to guarantee that your final dataset is considered properly prepared.

This notebook also contains many short code examples to illustrate various data collection and preparation/preprocessing steps. Again, those code snippets are kept very simple on purpose, and practical implementation will require much more effort. In fact, data collection and data preparation is arguably the most time-consuming part when training machine learning models, including LLMs.

Data Collection¶

Types of Data¶

Datasets used to LLMs can be broadly categorized into two types: generalized data and specialized data. This distinction reflects the scope and purpose of the information being used. Generalized data encompasses a wide range of topics and writing styles, providing the model with a broad understanding of language and knowledge across domains. In contrast, specialized data focuses on specific fields or industries, allowing the model to gain deep expertise and perform well on domain-specific tasks. Recognizing the difference between these dataset types is essential for designing effective training strategies that balance versatility with precision.

General Data¶

Generalized data for training LLMs refers to a broad and diverse set of textual information drawn from a wide range of domains, topics, and sources. This type of data is not tailored to a specific industry or task, but instead is meant to give the model a wide-ranging understanding of human language, knowledge, and reasoning. The goal of using generalized data is to enable LLMs to perform well across many types of queries and tasks, from casual conversation to more formal or technical problem-solving, without requiring specialized training for each.

Generalized data ensures that LLMs can learn the structure, semantics, and nuances of language in a way that generalizes to new and unseen inputs. This data often includes examples of different writing styles, languages, dialects, and cultural references. By training on such a wide corpus, the model gains a foundational linguistic competence that can later be fine-tuned with more specific data if needed. Common examples of generalized data used in LLM training:

- Wikipedia articles

- News websites and journalism archives

- Public books (e.g., from Project Gutenberg)

- Online encyclopedias

- Scientific abstracts and open-access research papers

- Internet forums and Q&A sites (e.g., Stack Exchange)

- Social media posts and comments (filtered for quality and safety)

- Technical documentation (e.g., software manuals, open-source code comments)

- Web crawl data (filtered from the open internet)

- Public government records and reports

Specialized Data¶

Specialized data for training LLMs refers to domain-specific or task-specific information used to fine-tune or enhance a model’s performance in particular areas. Unlike generalized data, which covers a wide array of topics, specialized data is focused on a narrow subject area such as law, medicine, finance, or customer service. This type of data is used to adapt an LLM to perform more accurately and reliably in professional or technical applications where precision and domain understanding are critical.

Training with specialized data helps models develop a deeper grasp of industry terminology, context, and use cases. It enables the LLM to generate more accurate outputs, answer domain-specific questions, and follow specialized workflows or standards. This data is often curated, proprietary, and may include sensitive or confidential information, requiring strict handling and compliance measures. Examples of specialized data include:

- Electronic health records (EHRs) or clinical notes (for medical LLMs)

- Legal case documents and court rulings (for legal models)

- Financial reports, balance sheets, and investment analyses

- Technical manuals and engineering specifications

- Customer support chat logs and ticket data

- Scientific datasets in niche research fields

- Programming documentation and source code from specific libraries or domains

- Internal corporate documentation and knowledge bases

- Industry-specific compliance and regulatory texts

- Patent filings and intellectual property databases

Collection Methods¶

The collection and creation of large text corpora often rely on online resources due to the sheer volume, diversity, and accessibility of textual data available on the internet. Online platforms host vast amounts of written content across domains — ranging from news articles and social media posts to academic publications and user-generated content—making them invaluable for building representative and comprehensive language datasets. The internet provides a dynamic and up-to-date source of language use, capturing both formal and informal registers, emerging linguistic trends, and multilingual content that is difficult to obtain through traditional means.

There are three main methods for acquiring such data from online sources: downloading publicly available datasets, using publicly accessible APIs, and web scraping. Public datasets, such as those released by governments, research institutions, or open data platforms, offer structured and often pre-cleaned text data. APIs (Application Programming Interfaces) allow for controlled, often real-time access to content from websites or services like Twitter or Reddit. Web scraping, meanwhile, involves automatically extracting data from web pages that do not provide APIs or datasets, allowing researchers to access a wider range of unstructured content. Together, these methods form the foundation for scalable and efficient corpus construction in modern computational linguistics and natural language processing.

Public Datasets¶

Downloading publicly available datasets is the easiest and most efficient way to collect data for training LLMs or for other NLP tasks because these datasets are already curated, accessible, and cover a wide range of content types and domains. Unlike web scraping (see below) which often involves legal, ethical, and technical barriers, public datasets come with clear licensing terms, structured formats, and documentation — making them immediately usable for research and development. This streamlines the data collection process and significantly reduces the time, resources, and expertise required to gather large-scale text corpora. Since many of these datasets are updated regularly and maintained by academic or open-source communities, they also offer a reliable and sustainable source of data.

Here are some popular public datasets (among man others):

Common Crawl Corpus: The Common Crawl Corpus is a massive, publicly available dataset of web page data collected regularly by the nonprofit organization Common Crawl. It consists of petabytes of web content—HTML pages, metadata, and extracted text—crawled from billions of websites across the internet since 2008. The data is stored in standardized formats (like WARC, WET, and WAT files) and hosted on Amazon S3, allowing researchers, developers, and organizations to access and analyze web-scale data freely.

Wikipedia Article Dump: The Wikipedia Article Dump is a publicly available dataset containing the full content of Wikipedia, including articles, templates, and metadata, as of specific snapshot dates. These dumps are released regularly by the Wikimedia Foundation and include both the raw wikitext source (with all the markup and edit history) and optionally pre-processed XML or plain text formats. The most commonly used version for research and development is the current pages dump, which contains the latest version of each article without the full edit history. The dumps are free to download and serve as a reliable, consistent snapshot of human knowledge at a given point in time.

arXiv: The arXiv public dataset is a large, openly accessible collection of scientific papers from arXiv.org, a preprint repository widely used by researchers in fields like physics, mathematics, computer science, and more. The dataset contains metadata (such as titles, abstracts, authors, categories), full-text content (often in LaTeX or PDF format), and publication history for millions of academic papers. It is periodically released or made accessible via APIs, bulk downloads, and public datasets hosted by platforms like Kaggle or Semantic Scholar.

Standardized Project Gutenberg Corpus: The Standardized Project Gutenberg Corpus is a cleaned and structured version of the original Project Gutenberg collection, which contains thousands of public domain literary works, including novels, plays, essays, and poems. While the original Project Gutenberg texts can vary in formatting and metadata quality, the standardized version processes and normalizes the content to make it more consistent and suitable for computational analysis. This includes removing boilerplate text (like licensing info), correcting formatting issues, and tagging metadata such as author, title, and language.

Important: While publicly available datasets provide a convenient starting point for training LLMs, they still require significant quality control and preprocessing to ensure effective learning and reliable outcomes. These datasets may contain inconsistencies, duplicates, formatting errors, or low-quality content such as spam, boilerplate text, or irrelevant data. Without careful cleaning and filtering, such noise can negatively impact model performance, leading to issues like factual inaccuracies, poor grammar, or biased outputs. Moreover, even well-structured datasets may lack uniformity across sources in terms of language, style, or encoding, requiring normalization and alignment. Ultimately, although public datasets are easy to access, turning them into high-quality training data still demands thoughtful curation and engineering effort.

APIs¶

An API (Application Programming Interface) is a set of rules and protocols that allows different software systems to communicate with each other. In the context of web services, an API enables users or applications to request specific data or functionality from a server in a structured and predictable way — usually via HTTP requests that return data in formats like JSON or XML. APIs are commonly used to interact with services like weather apps, social media platforms, and public data providers without needing to scrape web pages or access databases directly.

To collect public data from websites, developers can use APIs provided by those sites to programmatically request and retrieve the data they need. For example, services like Wikipedia or arXiv offer public APIs that let users fetch tweets, article content, or research paper metadata respectively. By writing scripts to send repeated queries to these APIs, one can gather large datasets efficiently and legally, often with the ability to filter or customize the data being returned. This method is more reliable, scalable, and respectful of websites' structures and terms of use compared to web scraping.

Particularly for popular APIs, software libraries that provide a simplified, higher-level interface for interacting with an API. Instead of manually writing HTTP requests, handling authentication, and parsing raw responses (often in JSON or XML), such a wrapper library abstracts these details into easy-to-use functions or classes. This makes it faster and more convenient for developers to access API functionality without dealing with the complexity of the underlying protocol or data structures.

For example, instead of manually sending a request to the Twitter API endpoint and parsing the JSON response, a wrapper like Tweepy (for Python) allows you to call methods like api.user_timeline() or api.search_tweets() directly. These libraries often include built-in error handling, pagination, and rate-limit management, reducing boilerplate code and potential bugs. In short, API wrapper libraries boost developer productivity and make working with public data sources more intuitive and efficient.

For example, the wikipedia library provides a wrapper for Wikipedia to perform searches and get content such as full articles, summaries, links, images and more. For a minimal working example, let's perform a search using the search term "Python". Instead of manually writing and executing the required HTTP request, the library provides a method search() that wraps this HTTP request, making the code much leaner and less error prone. The code cell below shows the search for "Pyhon" and prints the top-3 results.

wiki_search_results = wikipedia.search("Python", results=3)

for rank, result in enumerate(wiki_search_results):

print(f"{rank+1}. {result}")

1. Python 2. Monty Python 3. Python (programming language)

With another method page(), we can now fetch an actual Wikipedia article. Again, this method simply wraps a corresponding HTTP request to the API. Let's fetch the article for Python the programming language — the correct title of the article we got from the search results (see above).

wiki_page = wikipedia.page("Python (programming language)")

The result is the Wikipedia article as an instance of a class of the wikipedia library. This class has multiple member variables and methods to access the actual data. For example, the code cell below shows the unique ID and title of the page — this information can be used to deduplicate data (see below).

print(wiki_page.pageid)

print(wiki_page.title)

23862 Python (programming language)

The actual content of the article is also stored in a member variable. Since the article for the Python programming language is quite long, the code cell below only prints the first several hundreds of characters.

print(f"{wiki_page.content[:1200]}...")

Python is a high-level, general-purpose programming language. Its design philosophy emphasizes code readability with the use of significant indentation. Python is dynamically type-checked and garbage-collected. It supports multiple programming paradigms, including structured (particularly procedural), object-oriented and functional programming. Guido van Rossum began working on Python in the late 1980s as a successor to the ABC programming language, and he first released it in 1991 as Python 0.9.0. Python 2.0 was released in 2000. Python 3.0, released in 2008, was a major revision not completely backward-compatible with earlier versions. Python 2.7.18, released in 2020, was the last release of Python 2. Python consistently ranks as one of the most popular programming languages, and it has gained widespread use in the machine learning community. == History == Python was conceived in the late 1980s by Guido van Rossum at Centrum Wiskunde & Informatica (CWI) in the Netherlands; it was conceived as a successor to the ABC programming language, which was inspired by SETL, capable of exception handling and interfacing with the Amoeba operating system. Python implementation began in Dec...

This content can now be added to a dataset for training an LLM.

Of course, there might not be a wrapper library for all APIs you want to access. In this case, you will need to write the actual HTTP requests to get the data. While this is generally also a straightforward task, the code will be a bit more verbose.

In some sense, the Wikipedia API is an exception since it does not require any access credentials (e.g., private keys). Most APIs, even if they provide access to public data, require access credentials like API to ensure secure and controlled usage. These credentials allow the API provider to track how the service is used, enforce rate limits, and prevent abuse such as spam, scraping, or denial-of-service attacks. By tying requests to specific users or applications, providers can monitor usage patterns and detect suspicious behavior. Additionally, access credentials enable access control and usage analytics. They allow API providers to offer different levels of service (e.g., free vs. premium tiers) and gather data on how their APIs are being used.

Web Scraping¶

If a website or online platform is not offering an API to access the data, it is often still possible to get the data through web scraping. Web scraping is the automated process of extracting data from websites by simulating human browsing behavior. It involves writing scripts or using tools to send HTTP requests to web pages, parse the HTML content, and extract specific information such as text, links, images, or tables. Web scraping is commonly used to gather data that is publicly visible on websites but not provided through structured APIs.

In many cases, web scraping in terms of simply getting the raw HTML source code can be very straightforward. The code below shows a minimal working example using the requests library that comes by default with most Python implementations. You can use this library to send HTTP requests to web servers, allowing you to retrieve or interact with web content programmatically. It simplifies making GET, POST, and other HTTP method calls, handling things like URL parameters, headers, and cookies with an easy-to-use interface.

To fetch a page, we can use the get() method which gets as its main input argument the URL of the page you want. In the code cell, below we again fetch the Wikipedia article about the Python programming language. But this time, not via the API but directly through fetching the HTML source code of the article page. We can extract the HTML using the text member variable of the response object as the result from the GET request.

response = requests.get("https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Python_(programming_language)")

wiki_page_html = response.text

Let's have a look at the first couple of hundreds of characters from the HTML source we have just received.

print(wiki_page_html[:1000])

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html class="client-nojs vector-feature-language-in-header-enabled vector-feature-language-in-main-page-header-disabled vector-feature-page-tools-pinned-disabled vector-feature-toc-pinned-clientpref-1 vector-feature-main-menu-pinned-disabled vector-feature-limited-width-clientpref-1 vector-feature-limited-width-content-enabled vector-feature-custom-font-size-clientpref-1 vector-feature-appearance-pinned-clientpref-1 vector-feature-night-mode-enabled skin-theme-clientpref-day vector-sticky-header-enabled vector-toc-available" lang="en" dir="ltr">

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8">

<title>Python (programming language) - Wikipedia</title>

<script>(function(){var className="client-js vector-feature-language-in-header-enabled vector-feature-language-in-main-page-header-disabled vector-feature-page-tools-pinned-disabled vector-feature-toc-pinned-clientpref-1 vector-feature-main-menu-pinned-disabled vector-feature-limited-width-clientpref-1 vector-feature-limited-width-content-enab

HTML does not just hold the actual content you see on a web page — like text, images, or links — but also includes instructions on how that content should be structured and displayed. These instructions come in the form of tags (like <h1>, <p>, <img>, and <a>) which tell the browser things like "this is a heading", "this is a paragraph", or "insert an image here". Beyond that, HTML can also include metadata (information about the page), like the page title, character set, and instructions for search engines — often found in the <head> section. It can also include links to external stylesheets (CSS for design) or scripts (JavaScript for interactivity), helping control how the page looks and behaves, even if those parts are not visible in the actual content. Extracting the actual content from a web page (e.g., the paragraphs of a Wikipedia or news article) we can use as training data is a separate step we will discuss in a bit.

Like with the API, Wikipedia makes fetching content through web scraping relatively easy; see the 2 or 3 lines of codes for the previous example. This is mostly because Wikipedia articles are (mostly) static websites and the website is "OK" with web scraping. However, web scraping is becoming more technically challenging because many modern websites are built using dynamic content and employ anti-scraping measures to protect their data.

Dynamic content: Instead of loading all the information at once with basic HTML, many websites now use JavaScript to load content after the page initially loads. This means tools like requests (which only fetch HTML) cannot see the real content. To deal with this, scrapers often need to use more advanced tools like Selenium or Playwright which simulate a real browser and can interact with the JavaScript.

Anti-scraping measures: More and more websites increasingly use techniques to detect and block bots. These include rate limiting, CAPTCHAs, requiring login sessions, checking headers for signs of automation, and even using services like Cloudflare to block suspicious traffic. To bypass these, scrapers need to mimic human behavior more closely, rotate IP addresses, manage cookies and sessions, and sometimes even solve CAPTCHAs.

Regarding the latter issue, web scraping exists in a legal grey area because whether it’s allowed often depends on how and what you're scraping, as well as the terms and conditions of the website. While scraping publicly available data is not automatically illegal, many websites explicitly prohibit automated access in their Terms of Service (ToS) — violating these terms could lead to legal action. The legal uncertainty also stems from different interpretations of what constitutes unauthorized access or data misuse. For example, scraping publicly visible information might be allowed in one jurisdiction but considered unauthorized access in another. Furthermore, scraping copyrighted content, personal data, or bypassing technical barriers (like CAPTCHAs or logins) can all raise serious legal risks. This is why it is crucial to check a site's ToS, consult legal advice if unsure, and respect ethical boundaries when scraping.

Data Extraction & Conversion¶

The datasets for training LLMs are often collected from online resources which are typically not stored or represented as "ready-to-use" plain text. Common formats like HTML, PDF, DOCX and others contain more than just the main written content — they also include a wide range of structural, formatting, and metadata information. In HTML, for example, there are numerous tags (<div>, <span>, <nav>, <script>, etc.) used to define layout, style, and functionality rather than meaningful content. PDF files often include visual layout data such as font positioning, headers and footers, page numbers, or embedded forms and images. DOCX files store rich formatting instructions (like bold, italics, styles, and comments), tracked changes, and even the identity of the author.

When preparing training data for large language models (LLMs), this extra non-textual information needs to be removed because it introduces noise and bias into the learning process. LLMs learn patterns in natural language — not in document formatting or web layout logic. If this metadata or formatting is left in, the model may waste capacity learning irrelevant structure (like how tables are aligned in PDFs or how navigation menus look in HTML), which dilutes its ability to understand and generate meaningful language. Cleaning and normalizing this data ensures the model focuses on pure linguistic content, leading to better generalization and more natural language generation.

By default, the pure linguistic content is represented as plain text containing the words, numbers, punctuation marks, etc. of a document. However, Markdown has become a preferred format for training large language models (LLMs) because it strikes an ideal balance between readability, structure, and simplicity — all of which help LLMs learn from high-quality, well-organized text. Markdown uses lightweight, human-readable syntax to represent things like headings, lists, code blocks, and links without the clutter of complex tags (like in HTML or DOCX). For example, a heading looks like # Heading, and a code block uses triple backticks — formats that are easy for both humans and models to interpret. This structure helps the model recognize patterns like "this is a title", "this is a section", or "this is code" which improves its ability to understand document layouts and respond with appropriately formatted output.

Additionally, Markdown is widely used in technical documentation, wikis (e.g. GitHub, Stack Overflow), blogs, and open-source datasets — many of which are rich, high-quality sources of natural language. In fact, Jupyter notebooks use Markdown to format narrative content! Because Markdown is both clean and expressive, it provides LLMs with clear training signals while minimizing noise, making it ideal for learning from structured yet natural text. So let's have a look at how to convert some common formats into plain text or Markdown.

HTML (Hypertext Markup Language)¶

HTML (HyperText Markup Language) is the standard language used to create and structure content on the web. It provides the basic building blocks for web pages by using a system of tags and elements to define things like headings, paragraphs, links, images, and other types of content. These tags tell web browsers how to display the content and how different elements relate to one another. HTML is not a programming language; it's a markup language, meaning it organizes and labels content rather than performs logic or calculations.

A major challenge when working with HTML is that it is not expected to be 100% correct. This means that web browsers are designed to be forgiving and can still display web pages even if the HTML code has errors or does not strictly follow the rules. For example, you might forget to close a tag like <p> (for paragraph), or nest elements incorrectly, and the browser will usually still try to interpret and render the page as best it can. This flexibility helps ensure that websites don’t break easily due to small mistakes, making HTML more accessible to beginners.

However, this poses challenges when it comes to using web pages as sources for training data. It is therefore recommended to use established libraries that are equally forgiving than web browsers. One of the more common libraries is BeautifulSoup that can parse poorly formatted or incomplete HTML and "fix" it internally, allowing you to navigate and extract data as if the HTML were valid. It provides an easy-to-use, Pythonic interface to search and modify the HTML DOM tree using tags, attributes, and text, even when the underlying HTML structure is messy. For example, the code cell below shows how to convert a variable with HTML into the internal representation of BeautifulSoup using our Wikipedia article we have scraped previously.

# Parse HTML

wiki_soup = BeautifulSoup(wiki_page_html, 'html.parser')

We can now use the provided API to navigate to the document and extract the bits we are interested in. The find_all() method in BeautifulSoup is used to search the entire HTML document and return a list of all elements that match a specific tag, attribute, or other criteria. It is commonly used for extracting multiple elements, such as all <div> tags, all links (<a> tags), or all paragraphs (<p> tags) on a page. Paragraphs are often used to mark up parts of the main content. For example, the code snippet below prints the first three (non-empty) paragraphs of our Wikipedia article.

for idx, p in enumerate(wiki_soup.find_all("p")):

if p.text.strip() != "":

print(p.text)

if idx >= 3:

break

Python is a high-level, general-purpose programming language. Its design philosophy emphasizes code readability with the use of significant indentation.[33] Python is dynamically type-checked and garbage-collected. It supports multiple programming paradigms, including structured (particularly procedural), object-oriented and functional programming. Guido van Rossum began working on Python in the late 1980s as a successor to the ABC programming language, and he first released it in 1991 as Python 0.9.0.[34] Python 2.0 was released in 2000. Python 3.0, released in 2008, was a major revision not completely backward-compatible with earlier versions. Python 2.7.18, released in 2020, was the last release of Python 2.[35]

The text property of a BeautifulSoup object (or any tag object) returns all the text content within the HTML element, with all HTML tags stripped out. It is useful when you want to extract just the readable text from a tag or an entire HTML document. However, note that any tags between the <p> tags get also removed. This means that, for example, the information about links or text decorations also get removed.

While we can use BeautifulSoup to preserve all required information — and potentially convert them into Markdown — there are also libraries simplifying this process. For example, The html2text library is a Python module that converts HTML content into clean, readable Markdown-formatted plain text. It is especially useful when you want to extract text from web pages or emails while preserving some of the structure—like headings, links, bold text, and lists — without keeping the raw HTML tags. Unlike simply stripping out HTML tags, html2text maintains formatting elements in a way that is both lightweight and meaningful.

The code cell below shows a bit more advanced example for processing Wikipedia articles using both BeautifulSoup and html2text. First, we use BeautifulSoup to extract the main part of the article — notice that this requires to know how to find those parts (here the <div> element with the id mw-content-text). Since the main content also includes the commonly featured info box, we use the find() and decompose() methods of BeautifulSoup to find and remove this info box. Lastly, we let html2text convert the remaining HTML source code into Markdown.

# Parse HTML

wiki_soup = BeautifulSoup(wiki_page_html, 'html.parser')

# Find DIV the holds the main content of the Wikipedia article

wiki_page_html_content = wiki_soup.find("div", {"id": "mw-content-text"})

# Remove info box with tabular data

wiki_page_html_content.find("table", {"class": "infobox vevent"}).decompose()

# Convert HTML to markdown

wiki_page_markdown_content = html2text.html2text(str(wiki_page_html_content))

# Print the first 1,000 characters of the page in Markdown format

print(f"{wiki_page_markdown_content[:1000]}...")

General-purpose programming language **Python** is a [high-level](/wiki/High-level_programming_language "High-level programming language"), [general-purpose programming language](/wiki/General- purpose_programming_language "General-purpose programming language"). Its design philosophy emphasizes [code readability](/wiki/Code_readability "Code readability") with the use of [significant indentation](/wiki/Significant_indentation "Significant indentation").[33] Python is [dynamically type-checked](/wiki/Type_system#DYNAMIC "Type system") and [garbage-collected](/wiki/Garbage_collection_\(computer_science\) "Garbage collection \(computer science\)"). It supports multiple [programming paradigms](/wiki/Programming_paradigm "Programming paradigm"), including [structured](/wiki/Structured_programming "Structured programming") (particularly [procedural](/wiki/Procedural_programming "Procedural programming")), [object-oriented](/wiki/Object-oriented "Object-oriented") and [functional programmi...

Notice how this output has preserved the information about links and text decorations using the Markdown format.

Overall, it is important to keep in mind that converting HTML to Markdown is often not always accurate, even with established libraries, because HTML is far more expressive and flexible than Markdown. HTML supports complex layouts, nested structures, and visual elements (like tables, forms, CSS styling, and JavaScript interactions) that simply do not have direct equivalents in Markdown. Markdown is a simplified markup language designed for readability and ease of use, not for full-fidelity representation of web pages. As a result, during conversion:

- Layout and styling are lost (e.g., CSS classes, inline styles).

- Complex elements like tables, forms, and embedded media may be converted imperfectly or omitted entirely.

- Nested HTML tags can produce unexpected or broken Markdown formatting.

- Some HTML-specific constructs (like

<span>,<div>, or custom elements) have no Markdown equivalent and may be ignored or flattened in ways that lose meaning.

Because of these limitations, conversions often require manual cleanup or adjustment, especially when accuracy and structure are critical.

PDF (Portable Document Format)¶

PDF (Portable Document Format) is a file format created by Adobe that lets you share documents while keeping their original layout, fonts, images, and formatting the same on any device or computer. Whether you're reading a PDF on a phone, tablet, or desktop, it looks exactly the way the author intended. PDFs are often used for things like reports, resumes, eBooks, and forms because they are great at preserving how a document looks, including multiple columns, headers, page numbers, and graphics. But because of this fixed layout, extracting just the main text (for example, for machine learning or editing) can be tricky — it may include hidden formatting, repeated headers, or jumbled reading order that is not obvious to the human eye.

The PDF format is designed primarily for presentation, not structure — meaning it focuses on how content looks on a page rather than how it is logically organized. As a result, when converting a PDF to Markdown, it is difficult to accurately extract and reconstruct elements like paragraphs, headings, lists, or tables, because these are not explicitly marked in the file. Instead, text is positioned using coordinates, often in fragments, across a fixed layout. This makes it hard to tell where one section ends and another begins, especially with multi-column layouts, overlapping elements, or repeated headers and footers. Markdown, by contrast, requires clean, hierarchical structure, so bridging this gap requires sophisticated models to interpret layout, semantics, and reading order — making PDF-to-Markdown conversion a complex and error-prone task.

However, the omnipresence of PDF and desire to extract the content to train LLMs spurred the development of many sophisticated libraries that try to convert a PDF to Markdown as accurately as possible. One of those libraries, and which we will use for an example, is marker-pdf. This library is an advanced tool designed to extract clean, structured text from PDF documents by combining traditional layout analysis with machine learning models. Unlike basic PDF parsers that simply dump text based on coordinates, marker-pdf intelligently interprets document structure — such as headings, paragraphs, lists, tables, and reading order — even in complex layouts. Its strength lies in its ability to produce high-quality, semantically meaningful output (often in Markdown-like form), making it especially useful for preparing PDF data for machine learning, natural language processing, or content repurposing where preserving the logical flow of information is critical.

In the marker‑pdf library, the PdfConverter class is what actually handles the core logic of reading and converting PDF files into your desired output format—such as Markdown, HTML, JSON, or extracted document chunks. Under the hood, it performs the following main steps:

- Initializing various models (e.g. layout detection, OCR, text recognition, table detection, and inline math detection) to work together seamlessly.

- Rendering each page of a PDF, which involves loading the file from a path or URL, running layout analysis to segment the page into blocks, applying text/OCR, table parsing, and inline math recognition and constructing a structured “rendered” object with all detected elements.

- Passing the rendered output to a renderer such as Markdown but also HTML or JSON, to turn the parsed document into a string output.

- Returning the fully rendered representation, which is then usually post-processed to extract text, images, and other artifacts.

The code snippet below shows a minimal example of extracting the text form as PDF and converting it into the Markdown format.

converter = PdfConverter(

artifact_dict=create_model_dict(),

)

rendered = converter(example_pdf)

pdf_doc_markdown, _, _ = text_from_rendered(rendered)

Recognizing layout: 100%|███████████████████████████████████████████████| 1/1 [00:01<00:00, 1.88s/it] Running OCR Error Detection: 100%|██████████████████████████████████████| 1/1 [00:00<00:00, 13.13it/s] Detecting bboxes: 0it [00:00, ?it/s] Detecting bboxes: 0it [00:00, ?it/s]

pdf_doc_markdown is a string variable that holds the text content of the PDF as Markdown; so let's just print it:

print(f"{pdf_doc_markdown}")

# Data Preparation for Training LLMs ### 1 Introduction Data preparation is a critical foundational step in training large language models (LLMs), involving the collection, cleaning, formatting, and structuring of vast amounts of textual data to ensure quality, diversity, and relevance. This process includes tasks such as deduplication, normalization, tokenization, filtering harmful or low-quality content, and balancing data across domains and languages to minimize bias and improve model performance. Properly prepared data enables LLMs to learn effectively, generalize across tasks, and generate coherent, informative responses, making data preparation as essential to success as model architecture or training techniques. ## 2 Data Collection Data collection for training large language models (LLMs) involves gathering extensive and diverse text sources from the internet, books, academic articles, and other publicly available materials. The goal is to compile a broad and representative dataset that captures the richness of human language, knowledge, and context. This stage is crucial, as the quality and diversity of collected data directly impact the model's capabilities and performance. #### 2.1 Public Datasets ... 2.2 APIs ... ### 2.3 Web Scraping ...

Notice that the output — but this might depend on the exact version of the markdown-pdf version you have installed, the conversion of the PDF into Markdown may not be perfect — you may want to look at the original PDF to observe the discrepancies. Again, converting a PDF to Markdown using libraries like markdown-pdf is challenging because these tools typically rely on basic text extraction without fully understanding the PDF's layout or semantic structure. PDFs do not store content in a logical reading order, so reconstructing elements like headings, lists, or tables in clean Markdown often leads to formatting errors or missing content. This makes the conversion process inherently lossy and inconsistent.

DOCX¶

DOCX is a widely used file format for word processing documents, developed by Microsoft as part of the Office Open XML (OOXML) standard. Introduced with Microsoft Word 2007, DOCX replaced the older DOC format to provide better compression, improved data recovery, and enhanced compatibility across platforms. The format stores documents as a collection of XML files and associated resources, compressed into a single ZIP archive. Due to its open and structured nature, DOCX allows for easier integration with other software, enabling developers to create, edit, or extract content without needing Microsoft Word itself. This has made DOCX the default format not only for Microsoft Word but also for many other word processors and online document tools, supporting consistent document formatting and content preservation across different systems.

Converting DOCX to Markdown is generally easier and more accurate than converting PDF. DOCX files are structured using XML and include clear semantic tags for elements like headings, lists, bold text, and links — features that align closely with Markdown syntax. This also means that there are a variety of libraries to convert DOCX to Markdown available. In the following short example, we use markitdown by Microsoft. First, we need to create in instance of the converter class:

md = MarkItDown()

Now we can use the convert() method to convert a specified DOCX document and print the Markdown output:

result = md.convert(example_docx)

print(result.text_content)

Data Preparation for Training LLMs # 1 Introduction Data preparation is a critical foundational step in training large language models (LLMs), involving the collection, cleaning, formatting, and structuring of vast amounts of textual data to ensure quality, diversity, and relevance. This process includes tasks such as deduplication, normalization, tokenization, filtering harmful or low-quality content, and balancing data across domains and languages to minimize bias and improve model performance. Properly prepared data enables LLMs to learn effectively, generalize across tasks, and generate coherent, informative responses, making data preparation as essential to success as model architecture or training techniques. # 2 Data Collection Data collection for training large language models (LLMs) involves gathering extensive and diverse text sources from the internet, books, academic articles, and other publicly available materials. The goal is to compile a broad and representative dataset that captures the richness of human language, knowledge, and context. This stage is crucial, as the quality and diversity of collected data directly impact the model's capabilities and performance. ## 2.1 Public Datasets ... ## 2.2 APIs ... ## 2.3 Web Scraping ...

In fact, markitdown also supports the conversion of PDF document, but marker-pdf typically does a much better job.

In short, open-source libraries play a crucial role in converting document formats like HTML, PDF, and DOCX into Markdown, enabling standardized and readable text representations. Tools such as html2text, marker-pdf, and markitdown — but also many others — allow you to extract and structure content from diverse formats, preserving key elements like headings, lists, and links. Markdown's simplicity and consistency make it ideal for processing and further text manipulation.

These conversions are especially valuable when creating datasets for training large language models (LLMs). By transforming rich-format documents into clean, lightweight Markdown, developers can compile diverse and high-quality training data with consistent formatting. This improves both the scalability of dataset creation and the overall quality of input used to train models in tasks like summarization, question answering, or content generation.

Preliminary Data Cleaning¶

Data cleaning is the process of refining and preparing a raw dataset — for example, the original pages and documents collected from the Web — to ensure it is of high quality, consistent, and safe for model training. This involves removing duplicates, filtering out low-quality or irrelevant content, eliminating personally identifiable information (PII), ensuring language consistency, and excluding harmful or offensive material. The goal is to create a clean, diverse, and representative dataset that helps the model learn effectively while minimizing the risk of bias, memorization, or the generation of inappropriate outputs.

We discuss all these steps in more detail in subsequent sections. The focus right now is on basic but very important preliminary data cleaning to ensure that steps such as data deduplication or quality-based filtering of content perform well. These preliminary data cleaning steps typically refer to removing noise or normalizing strings that represent a document.

Markup¶

Markup in a text document refers to special symbols or codes embedded within the text that describe its structure, formatting, or presentation, rather than being part of the content itself. Markup helps computers interpret how to render or process text, such as identifying headings, links, emphasis (bold/italic), or layout elements. Common examples of markup are HTML (HyperText Markup Language), Markdown, LaTeX, XML (eXtensible Markup Language), or BBCode (Bulletin Board Code).

Markup is essential for organizing and displaying text, but for training language models, it is often stripped away unless the model is specifically designed to understand structured or formatted input — like in the case of Markdown. For an example, let's consider a simple HTML document. In the code cell below, the given string will be rendered as "Words can be in bold or in italics."

html_string = "<p>Words can be in <b>bold</b> or in <i>italics</i>.</p>"

Here, removing the markup simply means removing all the HTML tags, which can efficiently be done using regular expressions (RegEx). The method remove_html_tags() uses a regular expression to replace all tags — that is, anything between and including the angled brackets — with an empty string, effectively removing all tags.

def remove_html_tags(text):

return re.sub(r'<[^>]+>', '', text, flags=re.IGNORECASE)

We can now apply this method on our example HTML document to remove all formatting information.

print(remove_html_tags(html_string))

Words can be in bold or in italics.

Note that the HTML source code for real websites is much more complex, and simply removing all the tags is unlikely to yield desired outputs. Libraries like BeautifulSoup are typically preferred over regular expressions for cleaning HTML documents because they are specifically designed to parse and manipulate HTML and XML, even when the markup is malformed or inconsistent. HTML is not a regular language, meaning it has nested and hierarchical structures that regular expressions struggle to handle reliably. BeautifulSoup understands these structures, allowing for more accurate, robust, and readable extraction or removal of elements based on tags, attributes, or content—something that's error-prone and brittle with RegEx alone.

Boilerplate Content¶

In the context of a text document, boilerplate content refers to sections of text that are repetitive, standardized, or non-informative and appear across many documents with little to no variation. This type of content is often automatically generated or reused verbatim, providing minimal unique or meaningful information for training purposes. In large-scale text datasets, boilerplate can dilute the quality of the data and introduce redundancy or noise, which is why it’s commonly removed during preprocessing.

Common examples of boilerplate include website headers and footers, cookie consent banners, navigation menus, copyright notices, disclaimers, and templated phrases like “subscribe to our newsletter” or “all rights reserved.” In academic or legal documents, boilerplate may include standardized legal clauses or citation formats. Identifying and removing such content helps ensure that language models focus on learning from substantive, diverse, and original language.

It is arguably intuitive that boilerplate content should be removed when creating a dataset to train large language models because it adds noise and redundancy without contributing meaningful linguistic or contextual variety. Since boilerplate text is often repeated across many documents—such as headers, footers, disclaimers, or template phrases—it can cause the model to overrepresent certain patterns or phrases, leading to biased or unnatural outputs. Additionally, boilerplate content tends to lack semantic depth or diversity, which reduces the overall quality and informativeness of the training data. By removing it, you ensure that the model learns from richer, more diverse, and contextually meaningful language, improving its ability to generalize, generate coherent responses, and understand nuanced inputs.

As mentioned before, the type and amount of boilerplate content typically depends on the types of documents and their representations. Particularly modern web pages contain a lot of boilerplate content because they are designed not only to present information but also to serve multiple functional, navigational, and commercial purposes. Elements like navigation bars, footers, cookie consent banners, social media links, advertisements, and user interface components (e.g., modals, carousels) are reused across pages to provide a consistent user experience and support business goals such as engagement and monetization. Additionally, content management systems (CMS) and templating frameworks often generate standardized layouts by default, embedding large amounts of repetitive HTML, scripts, and styling unrelated to the main content. This makes boilerplate both a byproduct of modern web design and a challenge for content extraction tasks.

A very basic method to remove boilerplate content from the HTML source code of a web page is to remove the content in HTML tags associated with boilerplate parts of the page. To give an example, consider the following very simple HTML document.

example_page_html = """

<html>

<head><title>Sample Page</title></head>

<body>

<header><h1>Site Header</h1></header>

<nav>Main navigation menu</nav>

<article>

<h2>Main Content Title</h2>

<p>This is the main article content.</p>

</article>

<aside>Related links and ads</aside>

<footer>Footer with contact info</footer>

</body>

</html>

"""

# Parse the HTML

soup = BeautifulSoup(example_page_html, "html.parser")

HTML tags like <header>, <footer>, <nav>, <aside>, <script>, and <style> serve structural and functional roles in organizing and enhancing web content. The <header> tag typically contains introductory content or navigation links relevant to the page or a section, while <footer> holds metadata, contact info, or copyright notices usually found at the bottom. The <nav> tag defines navigational menus that help users move through the site, and <aside> is used for tangential content like sidebars, callouts, or related links that are not central to the main narrative.

On the functional side, <script> is used to embed or reference JavaScript, enabling interactive features like form validation, dynamic updates, or analytics. The <style> tag allows for embedding CSS rules directly within the HTML document, defining how elements are displayed. These tags are essential in modern web development for separating content, design, and interactivity, but they often introduce boilerplate content when extracting the core textual information from a page.

Using the BeautifulSoup library, removing such content is quite straightforward; see the code cell below. First, we define all the tags we consider containing boilerplate code. We can then use the find_all() and decompose() methods of BeautifulSoup to remove and find those tags (incl. their content).

# Define boilerplate tags to remove

boilerplate_tags = ['header', 'footer', 'nav', 'aside', 'script', 'style']

# Remove the boilerplate elements

for tag in boilerplate_tags:

for element in soup.find_all(tag):

element.decompose()

To see the effect of the previous code, we can print the result HTML document as well as the final output after removing all HTML tags. The get_text() method in the BeautifulSoup library is used to extract all the visible text from an HTML or XML document, removing tags and returning a plain string. It concatenates the text from all descendant elements and is useful for retrieving the human-readable content of a page. The method also supports optional arguments like strip=True to remove leading/trailing whitespace and separator to specify how text segments are joined.

# Print cleaned HTML or text

cleaned_html = str(soup)

cleaned_text = soup.get_text(strip=True, separator="\n")

print("CLEANED HTML:\n", cleaned_html)

print("\nCLEANED TEXT:\n", cleaned_text)

CLEANED HTML: <html> <head><title>Sample Page</title></head> <body> <article> <h2>Main Content Title</h2> <p>This is the main article content.</p> </article> </body> </html> CLEANED TEXT: Sample Page Main Content Title This is the main article content.

It is important to keep in mind that website providers are encouraged, but not strictly required, to use semantic HTML tags—such as <header>, <footer>, <nav>, and <aside> — to indicate boilerplate or structural content. These tags are part of the HTML5 standard and are promoted as best practices because they improve accessibility, search engine optimization (SEO), and maintainability by giving structure and meaning to web content. However, there is no formal enforcement mechanism requiring developers to use these tags consistently. Many sites still use generic containers like <div> or <span> for layout purposes, sometimes with CSS classes (e.g., class="navbar" or class="footer"), which can obscure the semantic intent. As a result, tools that extract content must often rely on heuristics, tag names, and class patterns to detect and filter out boilerplate, since adherence to semantic tagging varies widely across websites.

Particularly for HTML documents — since they often contain a lot and diverse boilerplate content, an alternative to removing this content is to extract all relevant content (i.e., all non-boilerplate content). Extracting the main content from a single website is generally easy because its HTML structure and layout are consistent across pages. Once the relevant tags, classes, or patterns for the main content are identified (e.g., a specific <div> or <article>), they can be reliably targeted for extraction.

However, when automated Web scraping is used to collect a dataset, not all sites might be known a-priori. In this case more or less complex heuristics are applied to extract the main content of a page — together with looking at tags. For example, a long(er) multi-sentence paragraph in a page is more likely to represent (some part of) the main content than, say, the header/footer or navigation components.

Python offers several libraries for extracting the main content from web pages, with popular ones including Readability (via readability-lxml), BoilerPy3, and Goose3. These tools generally work by analyzing the HTML structure and applying heuristics to identify and score content-rich blocks. For example, they may look at tag types (<p>, <article>, etc.), text density, link-to-text ratios, and the size or depth of DOM nodes. The goal is to locate sections with high information density and minimal noise, assuming that main content is longer, contains more paragraphs, and has fewer links compared to boilerplate sections. This heuristic-based approach allows them to generalize across many websites without needing custom rules for each one.

For a short example, the Document class in the Readability library is a high-level interface used to extract the main content from an HTML document. It applies content extraction heuristics inspired by the original Readability.js algorithm to isolate the most relevant parts of a web page — typically the main article or body text — while removing boilerplate such as navigation, sidebars, and ads. When you create a Document object by passing raw HTML as input, it analyzes the structure and allows you to access cleaned output through methods like .summary() for the extracted HTML content; see the code cell below using the example HTML document we have created earlier.

doc = Document(example_page_html)

print(doc.summary())

<html><body><div><body id="readabilityBody">

<nav>Main navigation menu</nav>

<article>

<h2>Main Content Title</h2>

<p>This is the main article content.</p>

</article>

</body>

</div></body></html>

While <head> and <header> have been removed, <nav> has not (note: this output may depend on the exact version of the library). This shows that the implemented heuristics classify this part as main content. The reason for this might be that <nav> content typically contains several links which are not present in this example.

In general, extracting the main content from web pages using heuristics is challenging in practice because web pages vary widely in structure, design, and coding conventions. As mentioned before, there is no universal standard for how main content is marked up. Additionally, modern websites often include large amounts of non-content elements such as ads, navigation menus, popups, and dynamic content injected via JavaScript, which can confuse heuristic algorithms. Heuristic methods must rely on imperfect signals like text length, tag types, or link density to infer which sections are meaningful, and these signals are not always reliable — especially on content-light pages or those with unusual layouts. Furthermore, websites frequently change their design, breaking previously effective rules and requiring constant adaptation.

Unicode¶

Unicode is a universal character encoding standard that provides a unique number (called a code point) for every character, symbol, or emoji in nearly every language and writing system in the world. Its goal is to enable consistent encoding, representation, and handling of text across different platforms, programs, and languages. For example, the letter "A" is represented in Unicode as U+0041, while the Chinese character "你" is U+4F60.

Before Unicode, different systems used various encodings (like ASCII, ISO 8859, or Shift-JIS), which led to compatibility issues and data corruption when exchanging text between systems. Unicode solves this by standardizing how text is stored and transmitted. It supports over 100,000 characters and continues to expand to include new symbols, scripts, and even emojis. Unicode is the foundation of modern text handling on the web, in programming languages (like Python), and in operating systems.

However, Unicode also poses challenges when working with text data. For example, some Unicode characters look very similar because the Unicode standard aims to encode every character from all the world's writing systems, including those with overlapping visual designs. This can lead to the inclusion of characters that are nearly indistinguishable in appearance but are distinct in their linguistic, cultural, or technical usage. To give a simple example, have look at the following three Unicode characters:

print("\U00000027") # Apostrophe (equivalent to ASCII character)

print("\U00002019") # Right Single Quotation Mark

print("\U000002BC") # Modifier Letter Apostrophe

' ’ ʼ

Another issue with Unicode is that the same-looking character can be represented by different code points. For instance, the German umlaut "ä" can be a single code point (U+00E4), or a combination of two: the base letter "a" and a separate diacritic for the umlaut. While many characters use a single code point, others — especially those with diacritics — require multiple. Diacritics are small marks that modify pronunciation or meaning and are common in many languages, such as the acute ("é"), grave ("è"), or umlaut ("ä"). In Unicode, these are often encoded as combining characters that attach to a base letter, allowing for flexible and accurate representation of diverse scripts.

print("\U000000E4")

print("\U00000061\U00000308")

ä ä

This means, for example, that two texts that look like duplications to a human might not look like duplicates to a machine or algorithm. Ensuring a consistent use of unicode characters across a diverse set of documents from a diverse set of data sources is very challenging, and a more detailed discussion is beyond the scope of this notebook. However, to give an example, let's look at the simple use case of handling German umlauts (lowercase only).

sentence1 = "Der Bär hört die Hühner."

sentence2 = "Der Bär hört die Hühner."

Although both sentences might look the same — they are getting rendered the same way — on the byte/character level, they are different. We can confirm this by checking of both strings are the same using the basic equivalence comparison in Python.

if sentence1 == sentence2:

print("Both sentences are identical.")

else:

print("Both sentences are different.")

Both sentences are different.

As expected, both sentences are different. In fact, you cannot tell in which sentence which umlaut is rendered based on unicode code point with or without diacritics

In practice, there is typically no single meaningful way to address such issues. To show one simple approach for our context of handling German umlauts, we can define mapping from the code points using diacritics to code points not using them; see the code cell below. Note that we again limit ourselves only to the lowercase version of the German umlauts to keep the example simple.

unicode_map = {

"\U00000061\U00000308": "\U000000E4",

"\U0000006F\U00000308": "\U000000F6",

"\U00000075\U00000308": "\U000000FC"

}

We can normalize any string by replacing umlauts that are represented by diacritic code points. For example, we can do this using a regular expression together with our mapping. The method multiple_replace() implements this regular expression. Notice that this method takes any mapping as argument, making it easy to extend this idea beyond replacing German umlauts by curating a more comprehensive collection of mapping between code points.

def multiple_replace(mapping, text):

regex = re.compile("|".join(map(re.escape, mapping.keys())))

return regex.sub(lambda mo: mapping[mo.group(0)], text)

Let's apply the method multiple_replace() to both example sentences.

sentence1_mapped = multiple_replace(unicode_map, sentence1)

sentence2_mapped = multiple_replace(unicode_map, sentence2)

print(sentence1_mapped)

print(sentence2_mapped)

Der Bär hört die Hühner. Der Bär hört die Hühner.

Of course, both sentences still look the same — which should not be a surprise. However, let's now check again for equality.

if sentence1_mapped == sentence2_mapped:

print("Both sentences are identical.")

else:

print("Both sentences are different.")

Both sentences are identical.

Now, both sentences are indeed considered the same since they match character by character.

Overall, working with Unicode can be challenging in practice because documents from different sources often use varying encodings, character sets, and representations for the same symbols. When aggregating data from diverse origins — such as websites, PDFs, or text files—these subtle variations can lead to inconsistencies in processing, indexing, or matching content. Moreover, non-ASCII characters (e.g., emojis, accented letters, or non-Latin scripts) may be corrupted or misinterpreted if encoding is not properly detected or handled. Unicode allows visually similar or even identical characters to have multiple valid encodings — see our example for German umlauts. This inconsistency affects tasks like deduplication, search, or training machine learning models where text integrity is critical. Ensuring Unicode consistency requires explicit handling, normalization, and validation throughout the data pipeline — especially in multilingual or web-scraped datasets.

Data Quality¶

High-quality data is the foundation for training reliable and effective large language models (LLMs). When training data is clean, diverse, and representative, models are more likely to generate accurate, coherent, and unbiased outputs. However, most LLMs today are trained on massive datasets collected from the web — a source that is inherently noisy, redundant, and inconsistent. Web data includes everything from high-quality articles and research papers to low-quality user comments, duplicated content, spam, and misinformation. Without careful filtering and preprocessing, such data can introduce harmful biases, reduce factual accuracy, and impair the model’s ability to generalize.

Ensuring data quality in this context involves removing duplicates, filtering toxic or biased language, correcting formatting issues, and balancing across domains and perspectives. Semantic deduplication, for example, helps prevent the model from overfitting to repeated information, while content filtering helps minimize the spread of harmful or misleading text. By prioritizing data quality during dataset construction, researchers can significantly improve model performance, fairness, and trustworthiness. In essence, high-quality data not only shapes the capabilities of LLMs — it determines their ethical and practical reliability in real-world use.

Basic Quality-Based Filtering¶

In general, considering a text of document of low or high quality with respect to its inclision in a dataset to train LLMs is not always obvious. However, there often some general criteria — and thus corresponding filtering strategies — that mark a text as unsuitable to be used for training. Here are some basic strategies:

Heuristic filtering. Heuristic or rule-based involves applying a set of predefined rules or heuristics to filter out low-quality content. These rules are often based on common characteristics of undesirable text; for example:

- Length filters: Removing extremely short or unusually long documents, as they may be incomplete snippets or contain excessive boilerplate.

- Repetition filters: Identifying and removing documents with excessive n-gram repetition, which can indicate boilerplate, automatically generated content, or low-information text. This includes things like long lists of keywords or repetitive disclaimers.

- Punctuation and character filters: Removing documents with unusual character distributions, excessive special characters, or a lack of proper punctuation, which can indicate corrupted or poorly formatted text.

- Source-based filters: Exluding content from websites such low-quality forums, spam or phishing websites, or simply websites known to feature a lot of misinformation, toxic or bias content, etc.

- Harmful content filters: Identifying and removing toxic, explicit, or otherwise inappropriate content to improve the safety and fairness of the LLM. This often involves keyword lists, regular expressions, or more advanced content moderation techniques.

Statistical and embeddings-based filtering. These methods leverage computational techniques to assess data quality more broadly.

- Perplexity thresholding: Perplexity is a common evaluation metric in language modeling that measures how well a probabilistic model predicts a sequence of words. It quantifies the model’s uncertainty: lower perplexity indicates the model is more confident and accurate in its predictions, while higher perplexity suggests the model struggles to predict the next word. Lower-quality text often has higher perplexity (i.e., the model is less "surprised" by it, indicating it's less coherent or natural). Filtering based on a perplexity threshold using a small, pre-trained language model can help remove highly disorganized or nonsensical text.

- Outlier detection (e.g., using embeddings): Documents can be embedded into a vector space (e.g., using Sentence-BERT or other embedding models). Outliers in this space, especially those far from common clusters, may represent low-quality, irrelevant, or anomalous content.

- Readability scores: Using metrics like Flesch-Kincaid or SMOG readability to filter for a desired reading level. While not universally applicable, it can be useful for specific LLM applications.

Model-based filtering. This advanced approach uses other models (often smaller LLMs or classifiers) to assess the quality of the training data.

- Classifier-based filtering: Training a lightweight classifier (e.g., using fastText or a smaller BERT-style model) to distinguish between "high-quality" and "low-quality" text. This classifier is trained on a manually labeled dataset of good and bad examples. The classifier then scores unlabeled data, and only samples above a certain quality threshold are kept.

- LLM-as-Judge filtering: Leveraging a more capable LLM to act as a "critic" or "judge" to evaluate the quality of text snippets. This can involve prompting the LLM with specific criteria (e.g., coherence, factual accuracy, relevance) and asking it to assign a score or a qualitative assessment. This is particularly effective for filtering instruction-tuning datasets.

- Verification strategy: A more sophisticated approach involves using a nearly-trained LLM as a foundation and incorporating candidate data during the final training steps. The performance improvement (or degradation) on benchmark tasks then serves as a metric for data quality, allowing for efficient identification of high-quality data.

These strategies are often used in combination, forming a multi-stage filtering pipeline to progressively refine the dataset and ensure the highest possible quality for LLM training. There are also many other strategies aiming to implement some form of quality control. For example, GPT-2 has been trained on online content that was linked from Reddit and which received at least 3 karma points — in other words, some form of crowd-sourced quality control. Of course, any filtering potentially reduces the size of the training datasets. While quantity was once the sole focus, researchers now recognize that the quality of the data significantly impacts an LLM's performance, preventing issues like bias, misinformation, and poor generalization.

Data Deduplication¶

Duplicate training data poses several problems that can negatively affect both performance and efficiency of an LLM. When the same content appears multiple times in a dataset, the model may overfit to that repeated information, assigning it undue importance compared to more diverse or less-represented content. This can lead to skewed learning, where the model becomes biased toward certain styles, topics, or phrasing, reducing its ability to generalize and respond flexibly across a wide range of inputs.

Moreover, duplicate data wastes computational resources by artificially inflating the size of the dataset without adding new information. It can also increase the risk of memorization, where the model learns to reproduce specific passages verbatim, potentially exposing copyrighted or sensitive information. To mitigate these issues, data deduplication techniques are essential during preprocessing, helping to maintain a clean, diverse, and balanced training corpus that supports more accurate and ethical model behavior.

Duplicate data is very common when using web-sourced content to train large language models (LLMs) because the internet is filled with repeated, mirrored, and recycled information. Many websites republish the same articles, news stories, product descriptions, or documentation across different domains, while forums and social media often quote or copy content verbatim in replies, reposts, and threads. Search engine optimization (SEO) practices also lead to content duplication, as publishers frequently duplicate popular text to increase visibility. Additionally, web archives, translation sites, and content aggregators contribute further to redundancy by hosting multiple versions of the same material. Without careful deduplication during preprocessing, these repeated patterns can become overrepresented in the training data, skewing the model’s learning and efficiency.

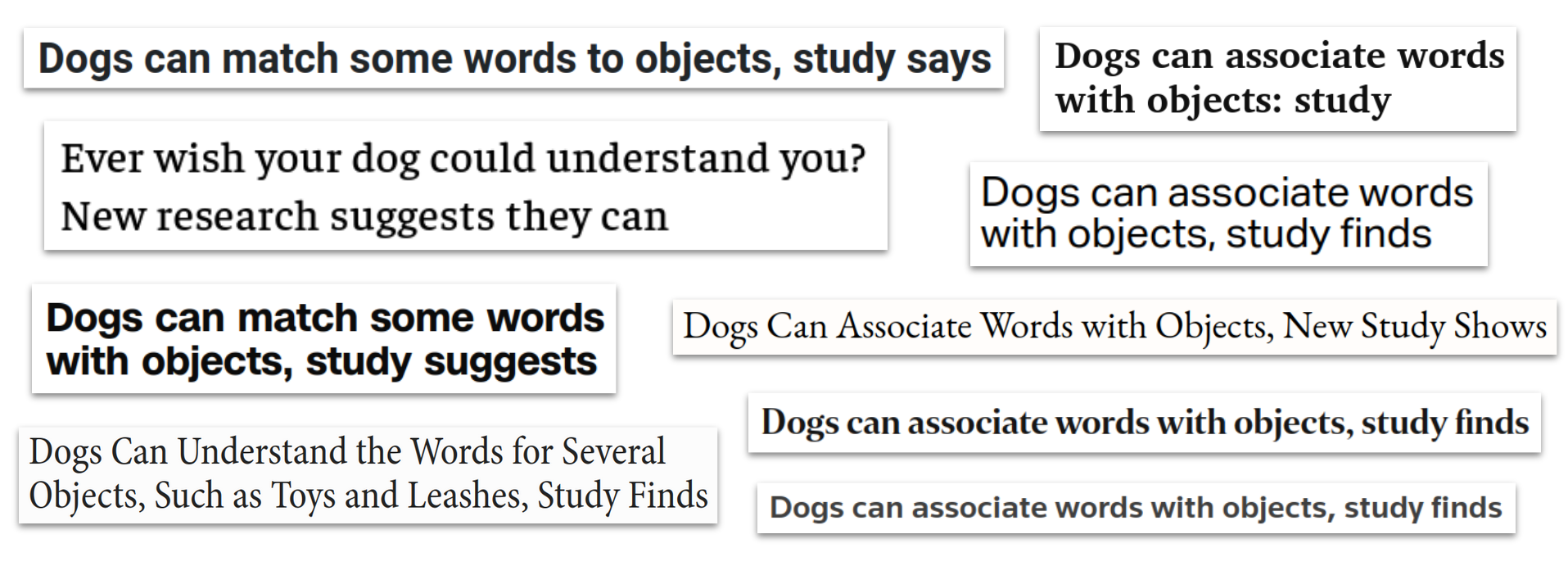

Example: Online News. A news agency (also called a wire service) is an organization that gathers, writes, and distributes news reports to other media outlets, while an online news site is a platform that publishes news directly to the public, often relying on content from multiple sources. News agencies like Reuters, AP, or AFP focus on producing fast, accurate, and broadly relevant stories that can be syndicated. Many news sites purchase the same articles from these agencies because it is more cost-effective and efficient than producing all original reporting — especially for breaking news or international coverage. By licensing agency content, news sites can quickly provide credible information to their audiences without having to maintain large, global reporting teams. To give a concrete example, the figure below shows a collection of news headlines citing and summarizing the same study about dogs.

Of course, this figure only shows the headlines and not the actual content. But like the headline, the content is often almost identical or at least very similar. Also keep in mind that there are many more sites that reported on that study.

Exact Deduplication¶

Exact duplicates in the context of strings and documents refer to texts that are identical character-for-character, with no differences in content, formatting, punctuation, or spacing. For example, two news articles with the exact same headline, body, and metadata would be considered exact duplicates.

Technically, comparing two strings for exact duplication is simple — computers can quickly determine if strings are identical using basic equality checks or hashing algorithms. For a trivial example, let's consider the following two headlines from articles collected from different online news sites.

headline1 = "dogs can associate words with objects, study finds"

headline2 = "dogs can associate words with objects, study finds"

headline3 = "dogs can associate words with objects; studies find"

headline4 = "dogs can connect words with things, experiments show"

Like all modern programming languages, Python directly allows to check if two strings are equal or not; see the code cell below.

if headline1 == headline2:

print("Both headlines are exact duplicates")

else:

print("Both headlines are NOT exact duplicates")

Both headlines are exact duplicates