Disclaimer: This Jupyter Notebook contains content generated with the assistance of AI. While every effort has been made to review and validate the outputs, users should independently verify critical information before relying on it. The SELENE notebook repository is constantly evolving. We recommend downloading or pulling the latest version of this notebook from Github.

Data Batching for Training LLMs¶

Training Large Language Models (LLMs) involves processing vast amounts of textual data, often structured as continuous streams of documents. The way this data is segmented and organized into batches directly affects both the model's efficiency and the quality of the representations it learns. In this context, the development of robust and scalable batching strategies is essential — not only to maximize hardware utilization but also to preserve the linguistic and contextual integrity of the input. Document streams, which provide a sequential flow of text samples (e.g., books, articles, or web pages), pose unique challenges and opportunities for batch construction, particularly when aiming to maintain coherence across sequences while optimizing for parallelism.

Traditional batching methods in machine learning often rely on fixed-size token sequences or sentences sampled independently from a large corpus. While effective in smaller settings, these methods can fall short when applied to LLMs trained on document streams, where context continuity and data ordering matter. For example, random sampling might break semantic flow, leading the model to learn representations that ignore broader discourse structure. This motivates the exploration of strategies that more carefully align the structure of batches with the document stream's natural boundaries, such as contiguous chunking, document-aware sampling, or packing strategies that reduce padding and maximize GPU efficiency.

One widely used technique is token packing, which combines multiple short sequences into a single input example of fixed length, minimizing padding and improving computational efficiency. This approach is particularly useful when training on datasets with variable-length documents or sentences. Another strategy is streaming batching, where documents are consumed in a sequential pipeline, and batches are constructed dynamically to preserve order and reduce fragmentation. More advanced strategies might involve curriculum learning-inspired batching, where documents are grouped by difficulty or topic progression to better align with the model's learning phase. Each of these strategies carries trade-offs in terms of complexity, memory usage, and the kind of contextual learning the model can achieve.

Ultimately, the choice of batch generation strategy is tightly coupled with training goals, model architecture, and computational constraints. As LLMs scale to trillions of parameters and datasets grow accordingly, efficient and context-sensitive batching from document streams becomes increasingly critical. It allows models to leverage long-range dependencies in natural language and achieve better generalization, while also ensuring that the infrastructure used for training is not a bottleneck. Research in this area continues to evolve, with hybrid and adaptive batching strategies emerging as promising directions for optimizing both performance and learning quality in large-scale language modeling.

Setting up the Notebook¶

Make Required Imports¶

This notebook requires the import of different Python packages but also additional Python modules that are part of the repository. If a package is missing, use your preferred package manager (e.g., conda or pip) to install it. If the code cell below runs with any errors, all required packages and modules have successfully been imported.

import torch

from torch.utils.data import Dataset, DataLoader

from transformers import AutoTokenizer

Preliminaries¶

There are a few preliminary comments to outline the scope of this notebook:

This notebook targets Transformers as the underlying neural network architecture for training a language model. This information is important as data preparation steps often depend on the used architecture. For example, the strategies explored in this notebook are not suitable for training language models using Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs).

Transformer rely on important concepts such as attention, masking, and positional encodings. While these topics will be briefly covered in this notebook, we recommend to check out the separate notebooks providing a deep dive into each of this topics

To make all visualizations, examples, and descriptions easier to understand, we assume that any input text is tokenized into proper words. Note that practical Transformer-based models typically rely on subword-based tokenizers (e.g., Byte-Pair Encoding, WordPiece). At the end, we include a practical implementation that does incorporate a pretrained subword-based tokenizer.

With these clarifications out of the way, let's get started...

Quick Recap: Transformer-Based Language Models¶

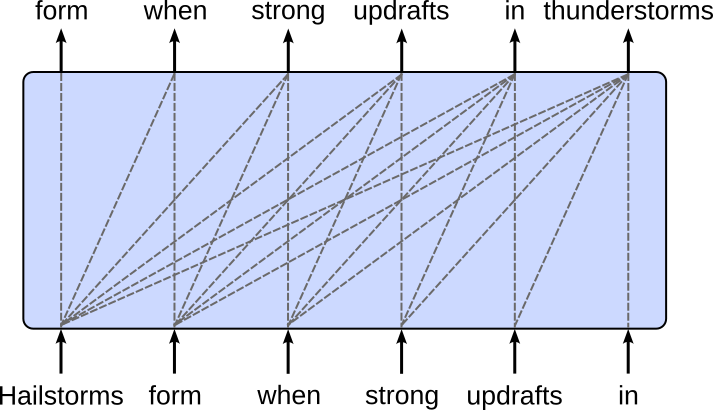

Most language models for text generation learn by doing a simple task: guessing the next word in a sentence. During training, the model is shown lots of text and, one word at a time, it tries to predict what comes next. For example, if the sentence is "The cat sat on the," the model might learn that "mat" is a likely next word. Every time it makes a guess, it compares its answer to the real word and adjusts itself to get better over time. Consider the following beginning a document

Hailstorms form when strong updrafts in thunderstorms carry raindrops into cold areas of the atmosphere, where they freeze and ...

Converting this document into input and target pairs training a next word prediction model, we would get the following list of samples — green phrases reflect the input and the red words reflects the target for the prediction:

- Hailstorms form

- Hailstorms form when

- Hailstorms form when strong

- Hailstorms form when strong updrafts

- Hailstorms form when strong updrafts in

- Hailstorms form when strong updrafts in thunderstorms

- Hailstorms form when strong updrafts in thunderstorms carry

- Hailstorms form when strong updrafts in thunderstorms carry raindrops

- Hailstorms form when strong updrafts in thunderstorms carry raindrops into

- Hailstorms form when strong updrafts in thunderstorms carry raindrops into cold

- ...

By repeating this process millions or even billions of times with different texts, the model learns grammar, facts about the world, and how ideas are usually expressed in language. This is what allows it to generate realistic and coherent text later on — because it has learned, word by word, how language works.

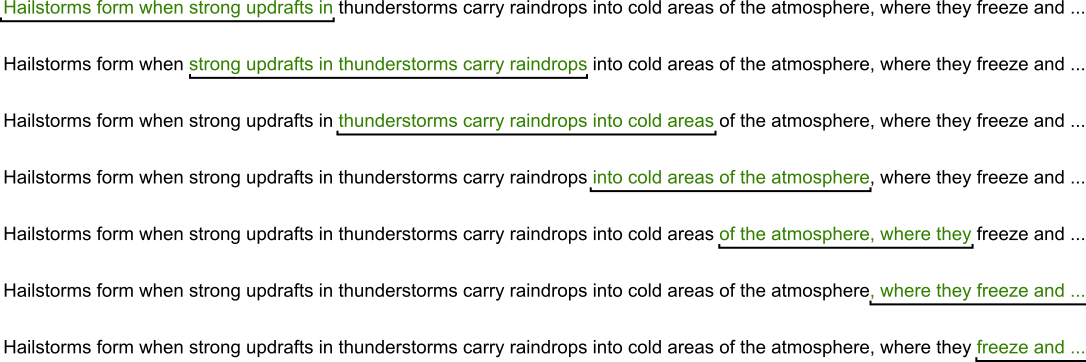

Using the Transformer decoder and causal masking, we input sequences of a fixed maximum length — the so-called context size — to train a language model. The context size of transformers is limited because they process input sequences using attention mechanisms that compare every token to every other token, which requires memory and computation that grows quadratically with sequence length. To keep training and inference efficient and manageable on current hardware, a fixed maximum length is set. Assuming our example document a context size of $6$, the training sample look look as follows:

A small context size of $6$ was only to simplify the visualizations. In practice, the context sizes of Transformer-based LLMs are typically in the range of several tens or hundreds of thousands, or even beyond. The table below lists some of the more popular foundational LLMs together with their context sizes.

| Model Provider | Model Name | Context Size (Tokens) |

|---|---|---|

| OpenAI | GPT-3.5 | 4,096 |

| GPT-4 | 8,192 (standard), 32,768 (GPT-4-32k) | |

| GPT-4o (2024) | 128,000 | |

| Anthropic | Claude 1 & 2 | 9,000 to 100,000 |

| Claude 3 (Opus, etc.) | Up to 200,000 | |

| Gemini 1.5 (Pro, Flash) | Up to 1,000,000 | |

| Mistral | Mistral-7B | 32,000 |

| Mixtral (MoE) | 32,000+ | |

| Meta | LLaMA 1 & 2 | 2,048 to 4,096 |

| LLaMA 3 (8B, 70B) | 8,192 | |

| Cohere | Command R+ | 128,000 |

| MosaicML | MPT-7B | 65,536 |

| xAI | Grok-1 | ~8,000 |

| Grok-1.5 (2025) | 128,000 |

Although practical context sizes seem quite large, the size of the training corpus in terms of the number of words/tokens is several magnitudes larger still. In other words, we cannot give the whole training corpus to the transformer but need to split it into suitable sizes. The default approach uses a sliding window to split the dataset into chunks and batches, as we will discuss in more detail in the following.

Batching with a Sliding Window¶

Recall that training dataset — at least conceptually — is a continuous stream of documents, with documents being separated by one or unique tokens. While different approaches exist, we assume that each document is followed by a $\text{[EOS]}$ (end of sequence) token. A document itself might contain hundreds, thousands or more words or tokens. Thus, assuming $\text{doc}_{i}$ is a list of tokens represents the $i$-th documents, our document stream has the following format:

In practice, our training data may consist of many such document streams so that each stream can fit into memory. However, this does not affect the underlying idea of the sliding window approach; performance consideration and optimization strategies (including parallel training across large compute clusters) are beyond the scope of this notebook.

Create Toy Document Stream¶

Right now, we also assume that our training data has already been tokenized and each token has been converted to its unique token index. This means that our document stream is a list of token indices, including the unique index for the special $\text{[EOS]}$ token. As we do not have to care about the exact index values here, let's create a random list (or 1-dimensional tensor) of token indices as our example document stream. The randint() method in PyTorch generates a tensor filled with random integers from a specified range [low, high) with a given size and optional data type and device. The code cell below uses this method to create a small 1-dimensional tensor containing $50$ random integers from $0$ (inclusive) to $100$ (exclusive).

# Set seed to ensure consistent results

torch.manual_seed(0)

# Create 1-dimensional tensor as example document stream

tokens = torch.randint(0, 100, size=(50,))

Of course, we can also print the created tensor tokens:

print(tokens)

tensor([44, 39, 33, 60, 63, 79, 27, 3, 97, 83, 1, 66, 56, 99, 78, 76, 56, 68,

94, 33, 26, 19, 91, 54, 24, 41, 69, 69, 49, 80, 81, 12, 63, 60, 95, 85,

22, 99, 11, 88, 78, 43, 96, 89, 71, 57, 83, 95, 82, 71])

Again, each integer entry in that tensor represents some word or token in our document stream.

Sliding Window Chunking¶

Like before, let's assume that we want to train a language model using a Transformer decoder with causal masking and a context size of $6$. Obviously even our small example document stream is too large as its length of $50$ exceeds the context size of $6$. The default approach to generate valid training samples — that is, where all training samples contain sequences of length $6$ — is to split the document stream into chunks of size $6$ using a sliding window.

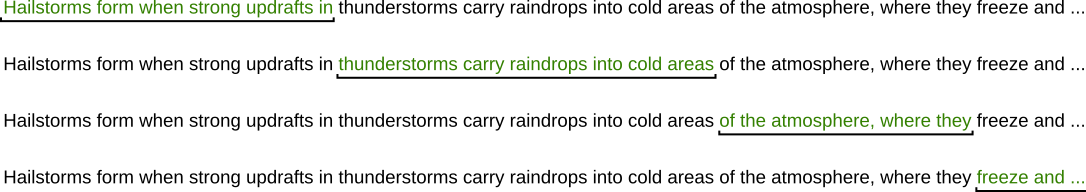

One basic approach is to generate non-overlapping chunks, this means that the sliding window is moved by the context size. The figure below illustrates this idea using our initial example sentence and a chunk size of $6$. Each sequence of words/tokens highlighted in green represent a chunk of size $6$; notice that punctuation marks such as commas are also an independent token (i.e, the chunk "of the atmosphere, where they" contains $6$ words/tokens).

The alternative is to move the sliding window by a smaller value than the context size, resulting in overlapping chunks. The figure moves the sliding window by $3$ words/tokens (i.e., 50% of the context size of $6$) over our example sentence to generate the chunks for our training samples.

When training a Transformer-based large language model using document streams, whether to use overlapping chunks depends on the goals of training and the constraints of computational resources. Generally, overlapping chunks can be beneficial because they help preserve continuity in long documents that are broken into fixed-length sequences, a common necessity due to memory limitations. Transformers typically have a maximum context window (e.g., 512, 1024, or 4096 tokens), so long documents must be split into smaller parts. Overlapping chunks ensure that tokens near the boundary of one chunk are not isolated from their neighboring context in the original document, allowing the model to learn smoother and more coherent representations across chunk boundaries.

The main advantage of using overlapping chunks in document streams is that they improve the model's ability to handle long-range dependencies and maintain a consistent narrative flow across chunks. This is particularly useful when training on text types where coherence and sequential understanding are crucial—such as stories, articles, or long-form conversations. With overlap, every token (especially those near the edges of chunks) is given the chance to be seen in a more complete context at least once during training, leading to better language modeling performance.

However, there are trade-offs. Overlapping increases the amount of data the model sees—but not in a unique way. It introduces redundancy, since the overlapping tokens are processed multiple times, which increases computational cost and training time without adding new information. This can also lead to inefficiencies in memory usage. Therefore, if compute resources are limited or if training speed is a priority, non-overlapping chunks may be preferred. In practice, a hybrid approach is often used—moderate overlap (e.g., 50%) is introduced to balance context preservation with efficiency, especially in early training stages when capturing document-level coherence is important.

Generating Targets¶

By default, we treat each chunk as the input of our Transformer model. For the training, we still need the targets (i.e., the target output sequence for a given input sequence). However, we already know that for the next word prediction task the target sequence is simply the input sequence shifted one word/token to the left. In line with the figure above, an example input-target pair for the Transformer decoder is:

Hailstorms form when strong updrafts in (input) $\Rightarrow$ form when strong updrafts in thunderstorms (target)

This generating of the target sequences by shifting the input sequences one word/token to the left is trivial to implement; as we will show below.

Basic implementation¶

The method chunk_tokens() in the code cell implements the sliding window approach and the generation of the targets in one go — again, assuming that the initial chunks represent the inputs. The argument max_len specifies the maximum length of the chunks to suit the context size of our Transformer model. The argument stride specifies by how many tokens we move the sliding window to get the next chunk. If stride=None (default), we set stride = max_len to yield non-overlapping chunks.

In the loop implementing the moving of the sliding window over the list of input tokens, the method extract both the chunks representing the inputs and the chunks representing the targets — the start and end index for the targets is the same as for the inputs increased by $1$ to get the shifting of the inputs by one word/token to the left. Note that the method then simply prints each pair of input and target chunk.

def chunk_tokens(tokens, max_len=6, stride=None):

# If stride=None, create non-overlapping chunks

if stride is None:

stride = max_len

# Move sliding window overall tokens with the given stride

for i in range(0, len(tokens)-max_len, stride):

# Extract chunk representing the model input

input_chunk = tokens[i:(i+max_len)]

# Extract chunk representing the model target

target_chunk = tokens[(i+1):(i+max_len+1)]

# Print input-target pair

print(input_chunk, "->", target_chunk)

To look at an example, we can call the method chunk_tokens() over our toy document stream containing 50 token indices; see the code cell below. Since we assume a context size of $6$ for our Transformer model, we naturally have to set max_len=6. Let's first try with the default argument stride=None (we could have also specified stride=6) to generate non-overlapping chunks.

chunk_tokens(tokens, max_len=6)

tensor([44, 39, 33, 60, 63, 79]) -> tensor([39, 33, 60, 63, 79, 27]) tensor([27, 3, 97, 83, 1, 66]) -> tensor([ 3, 97, 83, 1, 66, 56]) tensor([56, 99, 78, 76, 56, 68]) -> tensor([99, 78, 76, 56, 68, 94]) tensor([94, 33, 26, 19, 91, 54]) -> tensor([33, 26, 19, 91, 54, 24]) tensor([24, 41, 69, 69, 49, 80]) -> tensor([41, 69, 69, 49, 80, 81]) tensor([81, 12, 63, 60, 95, 85]) -> tensor([12, 63, 60, 95, 85, 22]) tensor([22, 99, 11, 88, 78, 43]) -> tensor([99, 11, 88, 78, 43, 96]) tensor([96, 89, 71, 57, 83, 95]) -> tensor([89, 71, 57, 83, 95, 82])

As expected, (a) the input chunks (and therefore the target chunks) do not overlap, and (b) the target chunks are the input chunk shifted one word/token to the left. However, you may have also noticed that some of the last token indices in put toy document stream are missing. Before we discuss this, let's first look at an example, where we use chunk_tokens() to create overlapping chunks by setting stride to a smaller value than max_len.

chunk_tokens(tokens, max_len=6, stride=3)

tensor([44, 39, 33, 60, 63, 79]) -> tensor([39, 33, 60, 63, 79, 27]) tensor([60, 63, 79, 27, 3, 97]) -> tensor([63, 79, 27, 3, 97, 83]) tensor([27, 3, 97, 83, 1, 66]) -> tensor([ 3, 97, 83, 1, 66, 56]) tensor([83, 1, 66, 56, 99, 78]) -> tensor([ 1, 66, 56, 99, 78, 76]) tensor([56, 99, 78, 76, 56, 68]) -> tensor([99, 78, 76, 56, 68, 94]) tensor([76, 56, 68, 94, 33, 26]) -> tensor([56, 68, 94, 33, 26, 19]) tensor([94, 33, 26, 19, 91, 54]) -> tensor([33, 26, 19, 91, 54, 24]) tensor([19, 91, 54, 24, 41, 69]) -> tensor([91, 54, 24, 41, 69, 69]) tensor([24, 41, 69, 69, 49, 80]) -> tensor([41, 69, 69, 49, 80, 81]) tensor([69, 49, 80, 81, 12, 63]) -> tensor([49, 80, 81, 12, 63, 60]) tensor([81, 12, 63, 60, 95, 85]) -> tensor([12, 63, 60, 95, 85, 22]) tensor([60, 95, 85, 22, 99, 11]) -> tensor([95, 85, 22, 99, 11, 88]) tensor([22, 99, 11, 88, 78, 43]) -> tensor([99, 11, 88, 78, 43, 96]) tensor([88, 78, 43, 96, 89, 71]) -> tensor([78, 43, 96, 89, 71, 57]) tensor([96, 89, 71, 57, 83, 95]) -> tensor([89, 71, 57, 83, 95, 82])

Now the input chunks and target chunks overlap by several tokens. But again, not all of the token indices present in the generated input target pairs. The reason for this is simply that our toy document stream cannot be split into input and target chunks all of length $6$. While $50$ (length of the toy document stream) is divisible by $6$ (context size), the last target chunk would require an additional token which is not there. As such, the last target chunk is not complete and therefore no valid training sample can be for formed.

In principle, we could "fill" the last input and target chunk with special tokens, e.g., $\text{[EOS]}$. However, the most straightforward approach is to ignore the last input-target pair — as done by our method chunk_tokens(). In practice, the training data is so large in terms of the total number of tokens that ignoring some of the last tokens simply does not matter at all. Just to give you some idea, the table below shows the total number of tokens that have been used to train different popular large language models.

| Model Provider | Model Name | Training Tokens (Approx.) |

|---|---|---|

| OpenAI | GPT-3 (175B) | ~300 billion |

| GPT-4 (speculative) | Estimated >1 trillion | |

| GPT-4o | Estimated >2 trillion (likely multilingual and multimodal) | |

| Anthropic | Claude 1 & 2 | Unknown, but likely 1–2T+ |

| Claude 3 (Opus, etc.) | Estimated 2-4 trillion | |

| Google DeepMind | Gemini 1.0 | Unknown |

| Gemini 1.5 | Likely >5 trillion (based on long context + mixture of modalities) | |

| Meta | LLaMA 1 | 1 trillion |

| LLaMA 2 (7B/13B/70B) | 2 trillion | |

| LLaMA 3 (8B, 70B) | 15 trillion tokens | |

| Mistral | Mistral-7B | Trained on 1.5 trillion |

| Mixtral (MoE) | Estimated 2-3 trillion | |

| Cohere | Command R+ | ~1.4 trillion |

| MosaicML | MPT-7B | ~1 trillion |

| xAI | Grok-1 | Unknown |

| Grok-1.5 | Likely >1-2 trillion |

So even if we talk about context sizes of several tens or hundreds of thousands of tokens, missing a few input-target pairs runs no risk of harming the overall performance of the model.

Overall, the splitting of a document stream into fixed-sized chunks using a sliding window is arguably very straightforward — although the choice if and by how much the chunks should overlap is not always obvious and might require some trial-and-error approaches in practice to get a sense of what works best. Our small chunk_tokens() was only to implement the core steps of the sliding window approach. In the following, the therefore look into some more practical implementations that we could actually use for training.

Practical Implementation¶

The splitting of our document stream into chunks that serves as input for our Transformer language model is a core requirement to facilitate the training of models. However, there are also other practical considerations such as the batching of training samples.

Neural networks such as Transformers are typically trained using batches — small subsets of the full training dataset — rather than the entire dataset (full-batch) or one example at a time (stochastic) because this strikes a balance between computational efficiency** and **learning stability. Processing the full dataset at each training step would be computationally expensive and slow, especially for large datasets, while using just one example per step introduces too much randomness in the learning process.

Batching allows the model to see enough examples at once to estimate a reliable gradient for updating weights, but keeps the computations manageable and parallelizable on modern hardware like GPUs. Moreover, training with batches introduces stochasticity** into the learning process, which helps the model escape local minima or saddle points in the loss landscape. This randomness often improves generalization compared to deterministic full-batch training.

Given the importance and prevalence of batching, most deep learning libraries such as PyTorch offer built-in mechanisms to simplify this process and support more advanced concepts such as parallel processing and training. In the following, we go through some examples of how we can use a text corpus to train a Transformer-based language model in practice.

Pretokenized Input¶

For the moment, let's again assume that our text corpus has already been tokenized and each word/token has been converted to an unique token index. In other words, the dataset is again a 1-dimensional tensor containing token indices, like the tokens variable we have created as our toy document stream.

For convenience and later use, we utilize the Dataset class in PyTorch, an abstract base class that provides a standard interface for accessing and managing data. To use it, you typically create a custom subclass that overrides two essential methods: __len__() to return the size of the dataset, and __getitem__() to retrieve a single data sample given an index. This design allows PyTorch to efficiently load and process data on-the-fly, which is particularly useful for large datasets that can't be fully loaded into memory.

One major benefit of the Dataset class is its flexibility. You can use it to wrap any type of data — images, text, audio, or even data from multiple sources — and apply custom transformations during retrieval. In our case, we implement our sliding window approach to split the token indices of our document streams into the input and corresponding target chunks with respect to the specified maximum length and stride. Notice how the __init__() method implements the same steps we saw in the method chunk_tokens(). However, instead of just printing the chunks, we now store all chunks in two lists.

class TokenDataset(Dataset):

def __init__(self, tokens, max_len=6, stride=None):

self.input_ids = []

self.target_ids = []

if stride is None:

stride = max_len

for i in range(0, len(tokens)-max_len, stride):

self.input_ids.append(torch.LongTensor(tokens[i:(i+max_len)]))

self.target_ids.append(torch.LongTensor(tokens[(i+1):(i+max_len+1)]))

def __len__(self):

return len(self.input_ids)

def __getitem__(self, idx):

return self.input_ids[idx], self.target_ids[idx]

So let's create an instance of our class TokenDataset using our toy document stream tokens as input. We use the arguments max_len=6 and stride=3 to generate overlapping chunks of size $6$ as seen before, but you are encouraged to try different values and inspect the results.

token_dataset = TokenDataset(tokens, max_len=6, stride=3)

Next, the DataLoader class in PyTorch is a utility that wraps around a Dataset object to efficiently manage the loading of data during training or evaluation. It handles batching of data, optional shuffling, and parallel loading using multiple worker processes. You can specify parameters like batch_size, shuffle, and num_workers to control how data is loaded and fed to your model. This makes it easy to iterate through large datasets in manageable batches, improving memory usage and training speed.

One of the key benefits of DataLoader is its ability to streamline and optimize the data pipeline, especially when working with large datasets or real-time data augmentation. By using multiple workers, it can prefetch and prepare the next batch while the model is training on the current one, effectively overlapping computation and data loading. This leads to more efficient GPU utilization and faster training times. Combined with a custom Dataset, the DataLoader makes it easy to build flexible, scalable, and high-performance training loops.

In the code cell below, we create an instance of the DataLoader class with the following arguments:

token_dataset: the instance of ourDatasetsubclass containing all the generated input and target chunks forming the individual pairs of training samplesbatch_size=4: the number of training samples in each batch. In practice the batch size may be much larger, but since our toy document stream is very small, we have to choose a small value to see any effect.shuffle=True: create new random batches for each iteration over the data loader. Shuffling the dataset into new batches after each training iteration (epoch) is common because it prevents the model from learning the order or patterns in the data sequence, which could lead to overfitting or poor generalization. Without shuffling, the model might repeatedly see the same examples in the same order, which can cause it to memorize specific batch structures or get stuck in suboptimal training dynamics. Shuffling promotes better mixing of examples across batches, leading to more robust and stable gradient estimates, and ultimately helps the model generalize better to unseen data.drop_last=True: ignores that last batch if it contains an insufficient number of training samples (i.e., less thanbatch_size). The last batch of a training dataset is often ignored if it contains fewer samples than the other batches to maintain consistent batch sizes, which simplifies the training process and avoids potential issues in layers that expect fixed input shapes (like batch normalization). Uneven batch sizes can also affect gradient calculations and performance optimizations, especially when using parallel hardware like GPUs. Ignoring the smaller final batch helps ensure uniformity and stability during training, even if it means slightly fewer training samples are used per epoch.num_workers=0: number of subprocesses used to load data in parallel. Increasingnum_workersallows data loading (including tasks like reading from disk and applying transformations) to happen concurrently across multiple CPU cores, which can significantly speed up training, especially with large datasets or complex preprocessing. Whennum_workers=0, it means that data loading will happen in the main process, i.e., no parallelism is used. This is simpler and useful for debugging, but it can become a bottleneck in training since the model must wait for data to be loaded and prepared before proceeding to the next batch.

token_dataloader = DataLoader(token_dataset, batch_size=4, shuffle=True, drop_last=True, num_workers=0)

During training a model, the data loader is used to generate and iterate overall batches. Since we do not train any model, the code cell below simply iterates through the data loader and prints the input-target pairs, each representing a single training sample.

for nr, batch in enumerate(token_dataloader):

print(f"==================== [Batch {nr}] ====================")

input_ids, target_ids = batch[0], batch[1]

for i in range(len(input_ids)):

print(input_ids[i], "==>", target_ids[i])

==================== [Batch 0] ==================== tensor([88, 78, 43, 96, 89, 71]) ==> tensor([78, 43, 96, 89, 71, 57]) tensor([27, 3, 97, 83, 1, 66]) ==> tensor([ 3, 97, 83, 1, 66, 56]) tensor([81, 12, 63, 60, 95, 85]) ==> tensor([12, 63, 60, 95, 85, 22]) tensor([69, 49, 80, 81, 12, 63]) ==> tensor([49, 80, 81, 12, 63, 60]) ==================== [Batch 1] ==================== tensor([24, 41, 69, 69, 49, 80]) ==> tensor([41, 69, 69, 49, 80, 81]) tensor([44, 39, 33, 60, 63, 79]) ==> tensor([39, 33, 60, 63, 79, 27]) tensor([76, 56, 68, 94, 33, 26]) ==> tensor([56, 68, 94, 33, 26, 19]) tensor([96, 89, 71, 57, 83, 95]) ==> tensor([89, 71, 57, 83, 95, 82]) ==================== [Batch 2] ==================== tensor([83, 1, 66, 56, 99, 78]) ==> tensor([ 1, 66, 56, 99, 78, 76]) tensor([22, 99, 11, 88, 78, 43]) ==> tensor([99, 11, 88, 78, 43, 96]) tensor([19, 91, 54, 24, 41, 69]) ==> tensor([91, 54, 24, 41, 69, 69]) tensor([60, 95, 85, 22, 99, 11]) ==> tensor([95, 85, 22, 99, 11, 88])

Two things you will notice: Firstly, if you run the previous code cell multiple times, the output will change in terms of an input-target pair being placed in different batches and at different positions within a batch. This is because we used shuffle=True to generate new random batches for each iteration over the data loader.

And secondly, the output is always missing two input-target pairs (assuming batch_size=4). This is because we have $15$ input-target pairs, which is not divisible by $4$. This means that the last batch would contain only $3$ pairs. However, since we used drop_last=True, we ignore this last batch. But again, due to the large sizes of practical training datasets, ignoring a few training samples does not matter at all — and through the shuffling, the small set of ignored training samples differs in each epoch.

Raw Text Input¶

We can now make our implementation slightly more advanced by getting rid of the assumption that input is already a list of token indices. Instead, we want the input to be a document stream as a list of text documents. To this end, the code cell below defines a simple list containing three short documents (in practice, a document may be a complete book).

documents = [

"This is the first document of our dataset to train a Transformer-based LLM. We assume that we tokenize the input text using the pretrained tokenizer",

"Good LLMs require huge datasets to train. The documents used for training should come from a wider variety of sources and domains.",

"Hailstorms form when strong updrafts in thunderstorms carry raindrops into cold areas of the atmosphere, where they freeze and **accumulate additional layers of ice as they are repeatedly lifted and dropped within the storm, eventually falling to the ground when they become too heavy for the updrafts to support."

]

Still, to keep this notebook simple, we make two simplifying assumptions. For one, we assume that the documents have been properly prepared and cleaned. Common data cleaning steps to prepare a corpus for training a language model include removing unwanted characters such as HTML tags, special symbols, or non-textual content, and normalizing text by converting it to lowercase, standardizing punctuation, and handling contractions or misspellings. It is also important to strip extra whitespace, remove duplicates, and optionally filter out irrelevant or low-quality content, like very short sentences or poorly structured text. Data preparation and cleaning is its own very important step and beyond the scope of this notebook.

And secondly, we use an existing implementation of a tokenizer. More specifically, we use a pretrained and publicly available subword-based tokenizer. The AutoTokenizer class in the Hugging Face transformers library used in the code cell below is a convenient wrapper that automatically loads the correct tokenizer class for a given pretrained model. Instead of manually selecting and initializing a specific tokenizer, you can simply use AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained("model_name"), and it will handle the underlying details based on the model's configuration. This makes it much easier to work with a wide variety of transformer architectures without needing to know the specifics of each one.

The main benefits of AutoTokenizer are ease of use, flexibility, and consistency. It simplifies the workflow when switching between models or integrating multiple models into a project. It also ensures compatibility between the tokenizer and the model, reducing the chance of mismatches in vocabulary or tokenization logic. Additionally, it supports loading tokenizers from both local directories and the Hugging Face Hub, making it ideal for both research and production environments.

For our example, we use the tokenizer of the "gpt2" model. It refers to the pretrained GPT-2 (Generative Pretrained Transformer 2) model developed by OpenAI, which can be used with Hugging Face’s transformers library to load both the model and its corresponding tokenizer. With AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained("gpt2"), we can load the tokenizer that matches GPT-2’s vocabulary and byte-pair encoding (BPE) scheme, ensuring compatibility with the pretrained weights and tokenization strategy used during training. Again, this is just one example, and we could also consider other pretrained models.

tokenizer = AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained("gpt2")

While the tokenizer will do all the heavy lifting of tokenizing and convert each token to its unique index under the hood, we have to make sure that we treat the special token separating two documents correctly. In other words, we have to use the same token as used by the pretrained tokenizer. To check which special tokens the tokenizer is using, we can check the special_tokens_map member variable of the AutoTokenizer class.

tokenizer.special_tokens_map

{'bos_token': '<|endoftext|>',

'eos_token': '<|endoftext|>',

'unk_token': '<|endoftext|>'}

We can see that the "gpt2" model only uses the single token <|endoftext|> which is perfectly fine for our case. So let's define this token as some constant for later use; see the code cell below.

EOS_TOKEN_GPT2 = "<|endoftext|>"

We can now convert our list of documents to a document stream — let's just call it text — by concatenating all documents into a single string and including the special token we just defined as the separator between documents. For this, we can use the built-in join() method of Python.

text = f" {EOS_TOKEN_GPT2} ".join(documents)

print(text)

This is the first document of our dataset to train a Transformer-based LLM. We assume that we tokenize the input text using the pretrained tokenizer <|endoftext|> Good LLMs require huge datasets to train. The documents used for training should come from a wider variety of sources and domains. <|endoftext|> Hailstorms form when strong updrafts in thunderstorms carry raindrops into cold areas of the atmosphere, where they freeze and **accumulate additional layers of ice as they are repeatedly lifted and dropped within the storm, eventually falling to the ground when they become too heavy for the updrafts to support.

We can now implement another Dataset subclass. The implementation of the class TextDataset in the code cell below is almost identical to the one of class TokenDataset from before. The main difference is that this class now expects as string as input and uses the provided tokenizer to tokenize the string and convert each token to its index. Once we have again have a list of token indices, we can use the same code to generate the input-target pairs using the sliding window approach.

class TextDataset(Dataset):

def __init__(self, text, tokenizer, max_len=6, stride=None):

self.input_ids = []

self.target_ids = []

if stride is None:

stride = max_len

# Tokenize text and convert tokens to token indices

tokens = tokenizer.encode(text)

for i in range(0, len(tokens)-max_len, stride):

self.input_ids.append(torch.LongTensor(tokens[i:(i+max_len)]))

self.target_ids.append(torch.LongTensor(tokens[(i+1):(i+max_len+1)]))

def __len__(self):

return len(self.input_ids)

def __getitem__(self, idx):

return (self.input_ids[idx], self.target_ids[idx])

Using again the arguments max_len=6 and stride=3 as before, we can create an instance of class TextDataset by providing our string text and the tokenizer instance as input arguments.

text_dataset = TextDataset(text, tokenizer)

The DataLoader class is agnostic to the implementation of the Dataset subclass. This means, we can create another instance of the DataLoader class the same way as before, only using our new TextDataset instance; for simplicity, we also use the same input arguments.

text_dataloader = DataLoader(text_dataset, batch_size=4, shuffle=True, drop_last=True, num_workers=0)

Like before, we can now iterate through the data loader and plot all training samples for each batch. Of course, the token indices can be much larger values since the vocabulary of the pretrained "gpt2" contains several tens of thousands of tokens — compared to our toy document stream with all values less than $100$.

for nr, batch in enumerate(text_dataloader):

print(f"==================== [Batch {nr}] ====================")

input_ids, target_ids = batch[0], batch[1]

for i in range(len(input_ids)):

print(input_ids[i], "==>", target_ids[i])

==================== [Batch 0] ==================== tensor([27140, 10128, 2421, 3236, 40522, 284]) ==> tensor([10128, 2421, 3236, 40522, 284, 4512]) tensor([ 1913, 2325, 1617, 82, 287, 18355]) ==> tensor([ 2325, 1617, 82, 287, 18355, 38563]) tensor([13363, 11241, 7509, 220, 50256, 4599]) ==> tensor([11241, 7509, 220, 50256, 4599, 27140]) tensor([38563, 3283, 6290, 49253, 656, 4692]) ==> tensor([ 3283, 6290, 49253, 656, 4692, 3006]) ==================== [Batch 1] ==================== tensor([ 284, 262, 2323, 618, 484, 1716]) ==> tensor([ 262, 2323, 618, 484, 1716, 1165]) tensor([4512, 13, 383, 4963, 973, 329]) ==> tensor([ 13, 383, 4963, 973, 329, 3047]) tensor([ 674, 27039, 284, 4512, 257, 3602]) ==> tensor([27039, 284, 4512, 257, 3602, 16354]) tensor([16354, 12, 3106, 27140, 44, 13]) ==> tensor([ 12, 3106, 27140, 44, 13, 775]) ==================== [Batch 2] ==================== tensor([ 220, 50256, 42913, 38563, 1296, 618]) ==> tensor([50256, 42913, 38563, 1296, 618, 1913]) tensor([1626, 262, 6388, 11, 4191, 7463]) ==> tensor([ 262, 6388, 11, 4191, 7463, 284]) tensor([ 5039, 3224, 11685, 286, 4771, 355]) ==> tensor([ 3224, 11685, 286, 4771, 355, 484]) tensor([ 484, 389, 7830, 13663, 290, 5710]) ==> tensor([ 389, 7830, 13663, 290, 5710, 1626]) ==================== [Batch 3] ==================== tensor([ 262, 5128, 2420, 1262, 262, 2181]) ==> tensor([ 5128, 2420, 1262, 262, 2181, 13363]) tensor([ 484, 16611, 290, 12429, 4134, 388]) ==> tensor([16611, 290, 12429, 4134, 388, 5039]) tensor([1212, 318, 262, 717, 3188, 286]) ==> tensor([ 318, 262, 717, 3188, 286, 674]) tensor([ 4996, 286, 4237, 290, 18209, 13]) ==> tensor([ 286, 4237, 290, 18209, 13, 220]) ==================== [Batch 4] ==================== tensor([1165, 4334, 329, 262, 2325, 1617]) ==> tensor([4334, 329, 262, 2325, 1617, 82]) tensor([ 3047, 815, 1282, 422, 257, 10595]) ==> tensor([ 815, 1282, 422, 257, 10595, 4996]) tensor([3006, 286, 262, 8137, 11, 810]) ==> tensor([ 286, 262, 8137, 11, 810, 484]) tensor([ 775, 7048, 326, 356, 11241, 1096]) ==> tensor([ 7048, 326, 356, 11241, 1096, 262])

We now have an implementation that works with any list of text documents as input — but again, assuming that these documents have all been properly prepared and and cleaned, which in practice is typically its own dedicated step.

Summary¶

When training a Transformer-based language model on continuous document streams, a sliding window approach is a common strategy used to generate training batches. This method addresses the fixed-length input constraint of Transformer models, which can’t process arbitrarily long texts at once. Instead of splitting documents randomly or truncating them, the sliding window technique processes long texts in overlapping segments, preserving the contextual flow across input chunks.

The sliding window works by taking a fixed-size window (e.g., 512 tokens) and sliding it across the text with a specified stride (e.g., 128 tokens). This generates overlapping sequences where each new window retains some tokens from the previous one. The overlap ensures that the model learns from context continuity, capturing dependencies that span across window boundaries—especially important for understanding long-term relationships in language. By adjusting the stride, you can control the trade-off between computational efficiency and contextual coverage.

This approach is particularly useful for streaming or unsegmented documents like books, logs, or transcripts, where there are no natural sentence or paragraph breaks to guide chunking. Unlike sentence-based batching, which might lose context at boundaries, the sliding window maintains a smoother transition between batches. This leads to better language modeling performance, especially for downstream tasks that rely on understanding long-range dependencies.

However, the sliding window method increases data redundancy, since overlapping tokens appear in multiple training samples. While this redundancy can improve learning of certain tokens, it also raises computational costs. To balance performance and efficiency, practitioners often tune the stride size and incorporate masking techniques during training to ensure the model doesn’t "peek" at future tokens when predicting. Overall, the sliding window approach is a powerful and practical solution for adapting long-form text to fixed-size Transformer inputs.