Disclaimer: This Jupyter Notebook contains content generated with the assistance of AI. While every effort has been made to review and validate the outputs, users should independently verify critical information before relying on it. The SELENE notebook repository is constantly evolving. We recommend downloading or pulling the latest version of this notebook from Github.

Masking in Sequence Models¶

Masking is a vital technique in sequence models like Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) and Transformers, where the input data often comes in the form of ordered sequences such as text, audio, or time-series signals. These models are designed to process and learn from sequential data, but in real-world scenarios, sequences frequently vary in length or contain missing, irrelevant, or future data points that should not influence the model's predictions. Masking provides a mechanism to control the flow of information within the model, ensuring that only valid and appropriate parts of the input are used during training and inference.

One of the primary reasons for the necessity of masking stems from the inherent nature of sequential data, such as text or time series. When training models on sentences of varying lengths, for instance, padding is often introduced to create uniform input sizes for batch processing. Masking becomes indispensable here to differentiate between actual data and the artificial padding, ensuring that the model doesn't process or learn from these meaningless padded tokens. Beyond handling variable lengths, masking is also vital for tasks like self-supervised learning, where parts of the input are intentionally masked and the model is trained to predict the hidden portions. This forces the model to learn contextual relationships and deeper understandings of the data.

Furthermore, masking techniques are critical for preventing information leakage and enabling more effective training paradigms. In NLP, for example, the concept of "attention masks" is widely used in Transformer architectures. These masks prevent the attention mechanism from attending to future tokens during training for tasks like language modeling, simulating a more realistic inference scenario where future information is unavailable.

Understanding and correctly implementing masking is essential for anyone working with sequence models. Improper masking can lead to information leakage, skewed training signals, or suboptimal attention behavior. As models like Transformers continue to dominate fields such as NLP and even expand into vision and multimodal tasks, mastering the use of masking is increasingly important. It ensures that models learn from data in a structured, meaningful way, preserving the temporal and logical integrity of the sequence data they are designed to process.

Setting up the Notebook¶

Make Required Imports¶

This notebook requires the import of different Python packages but also additional Python modules that are part of the repository. If a package is missing, use your preferred package manager (e.g., conda or pip) to install it. If the code cell below runs with any errors, all required packages and modules have successfully been imported.

import torch

from torch.nn.utils.rnn import pad_sequence

Preliminaries¶

Before delving into masking, there are a few preliminary comments to outline the scope of this notebook:

This notebook assumes that you are familiar with the concept of attention and multi-head attention. If not, we recommend that you first cover this topic before continuing.

Masking is a general concept deployed for a wide range of different neural network models and tasks. In this notebook, we focus on models such as Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) and Transformers handling sequential data (mainly text).

To make all visualizations, examples, and descriptions easier to understand, we assume that any input text is tokenized into proper words. Note that practical RNN and Transformer-based models typically rely on subword-based tokenizers (e.g., Byte-Pair Encoding, WordPiece).

Running Example¶

Throughout this notebook, we use the same running example to illustrate the different masking strategies and involved computations. Given our context of sequence models, we assume the following toy batch of sentences:

- "The cat ate"

- "The cat ate fish pie"

- "The cat ate fish"

Let's also assume we have the following vocabulary that maps between words and their word indices: {"The": 1, "cat": 2, "ate": 3, "fish": 4, "pie": 5, ...}. Notice that the vocabulary contains more words as we will add additional words later on. With this vocabulary, we can encode our batch of sentences as a batch of sequences containing the indices of the respective words as follows:

sequences = [

[1, 2, 3],

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5],

[1, 2, 3, 4],

]

As simple as this example might look, it will help us to understand all masking strategies.

Loss Masking¶

Loss masking is a technique used in machine learning, especially in models that process sequences like text, to control which parts of the output contribute to the training loss. When a model makes predictions over a sequence — such as words in a sentence — not every position may contain meaningful information for learning. Loss masking ensures that only the relevant positions are considered during loss computation, while the rest (like padding tokens or ignored tokens) are excluded.

The most common use of loss masking is to ignore padding tokens that are added to make sequences in a batch the same length. Without masking, the model might learn to predict these meaningless tokens, which can degrade performance. Loss masking is also important in tasks like masked language modeling, where only specific tokens are meant to be predicted, and the loss is computed solely at those positions. Overall, loss masking helps models focus on meaningful supervision and avoid learning from irrelevant or misleading parts of the input.

In terms of the involved computations, loss masking simply means turning off the loss for some positions in the output so that the model ignores them during training. This means that, although very important for a proper model training, loss masking is generally very easy to implement as it does not affect the model itself — loss masking is model-independent. Let's look at some of the most common reasons to apply loss masking in sequence models.

Padding Masking¶

Sequence models like Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) and Transformers — but also Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) used for sequence data — require padding to handle batches of variable-length sequences efficiently. In natural language processing tasks, input sentences or sequences often vary in length — see our example batch. However, for parallel processing and efficient use of GPU acceleration, it is essential to organize input data into fixed-size tensors. Padding involves appending special "padding" tokens (usually zeros or a designated symbol) to shorter sequences so that all sequences in a batch have the same length. This allows the model to process the batch in a single forward pass without dynamically adjusting for different input lengths.

For example, if you try to run the code cell below to convert our example batch into a PyTorch tensor, you would get an error. PyTorch Tensors are required to be "full" with respect to all their dimensions. However, our example batch is currently not full with respect to the sequence length dimension since all three sentences have a different length.

#sequences = torch.LongTensor(sequences) # This will throw an error!!!

In principle, RNNs and Transformers can intrinsically handle variable lengths but only if (a) if they process all sequences one by one (i.e., batch size of 1), or (b) if all sequences within at least the same batch have the same length. Training with a batch size of 1 is always possible but typically results in a much lower training speed as the training does not benefit from parallel processing compared to using larger batch sizes.

Ensuring that a batch contains only sequences of the same length can be a useful alternative from some use cases but it does require additional data preparation steps. It also prohibits that the training data can be randomly shuffled between epochs. Training data are often shuffled between epochs to prevent the model from learning spurious patterns or order-specific dependencies that don't generalize. Shuffling helps ensure that each mini-batch contains a diverse mix of samples, leading to more stable and generalized updates to the model’s parameters. This randomness improves convergence and reduces the risk of overfitting to the order of the data.

Thus, padding is a practical solution that enables efficient training and inference on sequence data with varying lengths. So let's pad our example batch and convert it into a proper PyTorch tensor. First we need to decide on the special word/token and its respective index. While not required, it is very common to set the index of the word representing the padding to $0$ — and we will see in a bit that this makes handling padding often quite convenient. The word/token can be basically any string, but it should be of course a string that is unique and does not already appear as another word/token in the dataset; here we go with "[PAD]":

PAD_IDX = 0

PAD_WORD = "[PAD]"

In other words, we extend our vocabulary by the new entry "[PAD]": 1. With these definitions in place, we can pad our example batch accordingly. First convert all individual sequences in the batch to tensors to serve as valued input to the built-in method pad_sequence() provided by PyTorch. The pad_sequence() method is a utility function that takes a list of variable-length tensors (typically representing sequences like sentences) and pads them so they all have the same length. It returns a single tensor where shorter sequences are padded with specified value to match the length of the longest sequence. Naturally, we use PAD_IDX as the passing value.

# Convert all sequences into tnesors

sequences = [ torch.LongTensor(s) for s in sequences ]

# Pad tensor with value 0

batch = pad_sequence(sequences, batch_first=True, padding_value=PAD_IDX)

# Show padded batch tensor

print(batch)

tensor([[1, 2, 3, 0, 0],

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5],

[1, 2, 3, 4, 0]])

batch is not a proper PyTorch tensor that can serve as input for a model for training or inferences. As such, we can also, for example, inspect the shape of the tensor:

print(f"Shape of batch tensor: {batch.shape}")

Shape of batch tensor: torch.Size([3, 5])

The shape of batch reflects our example data containing $3$ sequences and the longest sequences containing $5$ words. All initially shorter sequences have now been padded — extended by padding index $0$ to the same maximum length of $5$.

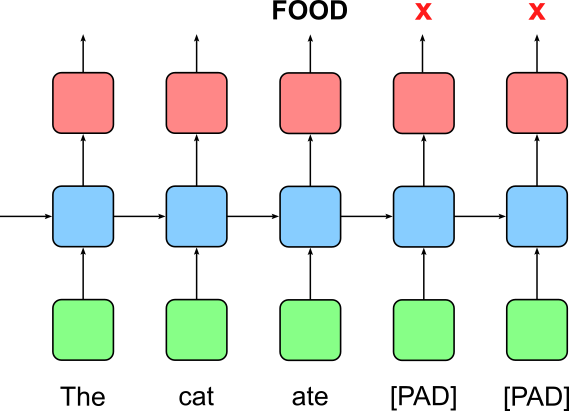

Of course, we now have to consider that the padding tokens do not carry any useful meaning themselves. As such, we have to ensure that during model training, these padding tokens are ignored. For example, assume we want to train RNN-based classifier to predict of a given sentence talks about topics such as "FOOD", "BEHAVIOR", "GROOMING", "HEALTH", etc. If we give this RNN our padded example batch, it will iterate over all five words, including the padding tokens if present. The figure below illustrates the idea for the first sentence "the cate ate".

We obviously want to ignore the output of the last two time steps associated with the padding tokens. Instead, we want to consider the output after the last proper word (here: "ate" at Index $2$) to calculate the loss during training. To find all the correct indices for all three sentences, we can simply count the number of non-zero elements for each sequence and subtract $1$ (since all arrays are zero-indexed). In the code cell below, we simply use the built-in method count_nonzero() to accomplish that.

# Count the number of non-zero elements for each sequence in the batch

batch_nonzero_indicies = batch.count_nonzero(dim=1) - 1

# Show indices

print(batch_nonzero_indicies)

tensor([2, 4, 3])

In other words, we want to calculate the loss at Index $2$ for the first sequence, at Index $4$ for the second sequence, and Index $3$ for the third sequence. Keep in mind that this assumes that we have performed right-padding, i.e., we added the padding tokens to the right side when extending the sequences. Also note how using $0$ as the padding index makes this step using the method count_nonzero() very easy.

Side note: Since this is such a common scenario, PyTorch provides the PackedSequence class for an easier and more efficient implementation. A PackedSequence in PyTorch is a data structure used to efficiently represent sequences of varying lengths, typically for use with RNNs. When dealing with batches of sequences (e.g., sentences of different lengths), padding is usually added to make them the same length. However, this padding can be wasteful and may negatively affect model performance. PackedSequence solves this by storing only the non-padded elements along with metadata (like sequence lengths) that allows PyTorch to keep track of the original batch structure. Using a PackedSequence allows RNNs to skip over padded elements during computation, leading to faster training and better handling of variable-length inputs.

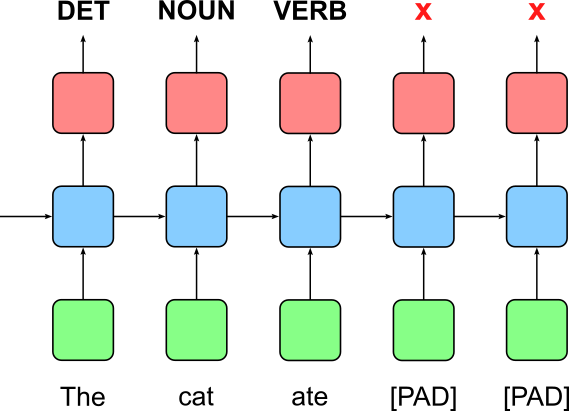

Let's consider another application where we want to use our example batch to train an RNN-based Part-of-Speech tagger. The figure below illustrate this training setup based on the first sentence "the cat ate". Again, since this 3-word sentence is parted if the padded batch where all sequences are of length $5$, by default (i.e., without using PackedSequence) the RNN will iterate over all five words and produce five outputs — and again, we want to ignore the last two outputs for the first sentence.

In simple terms, we are now interested in all indices of non-zero entries for each sequence. The code cell below creates a Boolean tensor with the same shape as batch with True in positions where there is a non-zero entry in batch; and False otherwise.

# Create a mask for non-zero elements

padding_loss_mask = (batch != PAD_IDX).float()

# Show binary mask

print(padding_loss_mask)

tensor([[1., 1., 1., 0., 0.],

[1., 1., 1., 1., 1.],

[1., 1., 1., 1., 0.]])

We can now use this mask to ignore the losses for all outputs of padding tokens. To sketch this idea, let's define a random tensor that contains all $5$ losses (with respect to all five words) and all $3$ sequences. This means that the tensor holding all the losses has the same shape as our padded batch.

# Create a random tensor with values between 0-1 to represent loss values

batch_losses = torch.rand_like(batch.float())

print(batch_losses)

tensor([[0.5135, 0.5513, 0.9017, 0.4005, 0.0784],

[0.4215, 0.5581, 0.8376, 0.8771, 0.9324],

[0.2851, 0.7234, 0.5639, 0.6350, 0.9162]])

To get the final aggregated loss, we can not multiply the tensor losses containing all losses with the padding mask; this will set the losses for padding positions to $0$. Lastly, we can sum up all losses and divide by the number of non-zero losses to calculate the mean. The mean loss is typically calculated for each batch to ensure that the learning signal remains consistent regardless of batch size or sequence length. Moreover, using the mean loss ensures comparability across different training iterations and facilitates learning rate tuning, since the magnitude of the loss (and gradients) remains within a predictable range.

# Calculate mean loss over all non-pad positions

batch_loss = (batch_losses * padding_loss_mask).sum() / padding_loss_mask.sum()

print(f"The mean loss for the example batch is: {batch_loss:.3f}")

The mean loss for the example batch is: 0.650

Side note: Again, in practice, PyTorch supports this step out of the box. The ignore_index argument in PyTorch loss functions, such as nn.CrossEntropyLoss, allows you to specify a target value that should be excluded from the loss computation. This is particularly useful when dealing with padded sequences in tasks like sequence modeling, where padding tokens are added to ensure uniform sequence length but do not represent meaningful data. By setting ignore_index to the padding token's value, you ensure that the model is not penalized for predictions made at those positions.

Masked Language Modeling¶

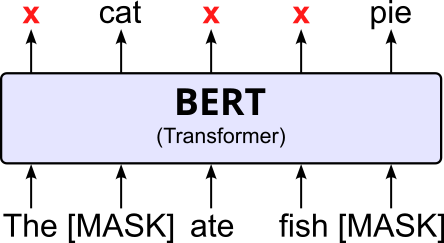

Masked Language Modeling (MLM) is a self-supervised learning task used to train language models to understand the structure and meaning of language. In MLM, some tokens in an input sentence are randomly replaced with a special token (e.g., "[MASK]"), and the model is trained to predict the original tokens based on the surrounding context. This encourages the model to learn deep bidirectional representations, as it must consider both the left and right context to make accurate predictions.

For example, given the sentence "the cat [MASK] fish pie", the model learns to predict the missing word "ate". This task is most famously used in models like BERT, where MLM allows the model to develop a strong understanding of word relationships, syntax, and semantics without needing labeled data. By training on large corpora with this objective, the model can later be fine-tuned for downstream tasks such as question answering, text classification, or named entity recognition.

To give an example, let's create another training batch that contains only the longest sentence for our initial example batch — simply to avoid for padding here — but replace some of the words with "[MASK]". For example, the original BERT model replaced ~15% of all words with "[MASK]":

- "the [MASK] ate fish [MASK]"

- "[MASK] cat [MASK] fish pie"

- "the cat ate [MASK] pie"

The figure below shows the basic learning setup using BERT with the Masked Language Model objective with respect to the first sentence "the [MASK] ate fish [MASK]", where the task is to predict the missing words "cat" and "pie".

The BERT model (and its variants) is based on the Transformer architecture and therefore returns an output for each input word. However, since we only care about the outputs at indices $1$ and $4$, we again need to apply loss masking. To illustrate this, let's first encode the masked example sentences from above into a tensor by introducing [MASK] as a new token to our vocabulary and assigning it the unique index $999$ (completely arbitrarily chosen):

MASK_IDX = 999

MASK_WORD = "[MASK]"

mlm_batch = torch.LongTensor([

[1, 999, 3, 4, 999],

[999, 2, 999, 4, 5],

[1, 2, 3, 999, 5]

])

print(mlm_batch)

tensor([[ 1, 999, 3, 4, 999],

[999, 2, 999, 4, 5],

[ 1, 2, 3, 999, 5]])

This batch tensor now allows us to derive the corresponding loss mask, which is again another tensor of the same shape mlm_batch. In this case we are interested in finding all positions where the word index is $999$ and therefore representing a masked word:

# Create a mask for non-zero elements

mlm_loss_mask = (mlm_batch == MASK_IDX).float()

# Show binary mask

print(mlm_loss_mask)

tensor([[0., 1., 0., 0., 1.],

[1., 0., 1., 0., 0.],

[0., 0., 0., 1., 0.]])

With this binary mask, we can now perform the same steps we have already seen to consider only the losses for the masked tokens as part of the calculation of the final loss for this batch:

# Calculate mean loss over all non-pad positions

mlm_batch_loss = (batch_losses * mlm_loss_mask).sum() / mlm_loss_mask.sum() # Mean loss over non-pad positions

print(f"The mean loss for the MLM example batch is: {mlm_batch_loss:.3f}")

The mean loss for the MLM example batch is: 0.505

Of course, in practice, when using the implementations of loss functions provided by PyTorch, we could use the ignore_index argument to handle all the selective loss calculations under the hood. This keeps the code cleaner, easier to maintain, and reduces the risk of introducing implementation errors.

Side note: Apart from the Masked Language Model (MLM) objective, BERT also implements a Next Sentence Prediction (NSP) objective for the model training. This objective helps the model understand the relationship between pairs of sentences, which is important for downstream tasks like question answering and natural language inference. During training, BERT is fed pairs of sentences: in 50% of the cases, the second sentence is the actual next sentence that follows the first one in the original text ("Is Next"), and in the other 50%, it is a randomly chosen sentence from the corpus ("Not Next"). The model is trained to predict which of these two cases applies. However, we have ignored the NSP object for our example as it does not add anything to our discussion about masking.

Custom Loss Masking¶

Padding masking and Masked Language Modeling (MLM) are both common and standard reasons for loss masking. Also, both applications apply loss masking to completely ignore certain losses by using binary mask — that is, the mask contains only $1$s and $0$s. However, the mask may also contain numerical values that can be interpreted as weights to increase or decrease the importance of a certain loss at a certain position. The list below outlines so example for other use cases of loss masking:

Missing data labels: An annotated dataset might accidentally or purposefully miss individual data items or labels. For example, a dataset for training a Part-of-Speech tagger might not come with tags/labels for numbers or other non-standard words. While we can introduce a default label (e.g., "OTHER"), we can also mask all the outputs for words or tokens that do not have a label. Sequence data might also miss complete items. Maybe the items where not (properly) recorded (e.g., when Optical Character Recognition (OCR) failed to recognize or word), or items where redacted (e.g., for privacy preservations).

Noisy or uncertain labels: Annotations may come with additional information how certain or uncertain a label is (e.g., expressed as a percentage from 0% to 100% certainty). For example, our Part-of-Speech dataset might have been labeled by 10 different annotators. Thus, for words where not all 10 annotators agree on the same PoS tag, we can decrease the importance of the losses for those based on the level of agreement: instead of multiplying the initial losses by $0$ we multiply them by values between $0$ and $1$.

Curriculum Learning: Loss masking for curriculum learning involves selectively including or excluding parts of a sequence from contributing to the loss based on their difficulty or relevance at a given stage of training. Instead of feeding easier examples first (as in traditional curriculum learning), this approach presents full sequences but masks out harder tokens initially, gradually unmasking them as the model improves. This allows the model to focus on learning simpler components first while still seeing the full input context. For example, in a sequence labeling task like Named Entity Recognition (NER), you might initially compute the loss only for easily recognizable entities like "John" or "London", masking out rare or ambiguous tokens like "Apple" (which could be a company or a fruit).

Attention Masking (Transformers)¶

So far, masking did not affect the inner workings of a model itself as loss masking is only concerned about which outputs should be considered for the training. While Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) may be trained more efficiently utilizing masking information — potentially performing less operations for sequences shorter than the longest sequence in a batch — this is not a required step as it does not affect the underlying training setup and objective.

However, the characteristics of the Transformer architecture requires that certain types of masking are part of the model itself. The main reason for this is that the attention mechanism, by default, computes the attention weights between all pairs of words in parallel — in contrast to RNNs that process sequences indeed sequentially. There are various reasons why adding masking to the attention mechanism is required. In the following, we focus on the two most common ones: padding (again) and autoregressive sequence generation (e.g., text generation in case of words as outputs).

Padding Masking — Attention Blocking¶

The motivate the problem of working with padded batches as input for the Transformer architecture, let's have another quick look at our example batch:

print(batch)

tensor([[1, 2, 3, 0, 0],

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5],

[1, 2, 3, 4, 0]])

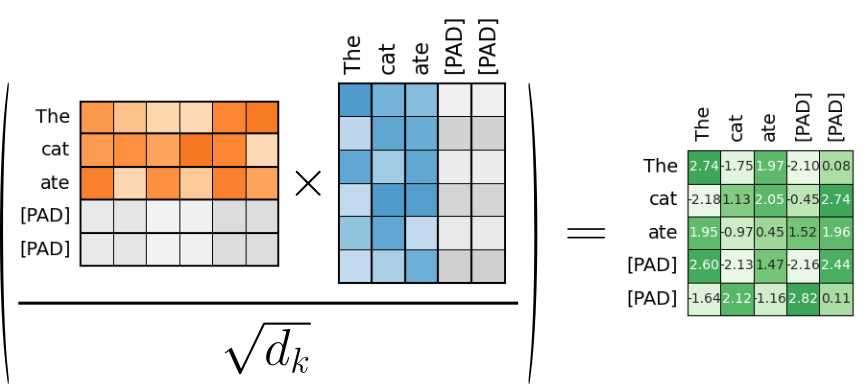

Recall the $0$ represents the padding token that we only added to create a proper PyTorch tensor, but does not carry any semantic information on its own. If we input this batch into a Transformer, the attention mechanism computes the attention scores between all pairs of words for each sequence, including the padding tokens. Recall that attention is calculated as

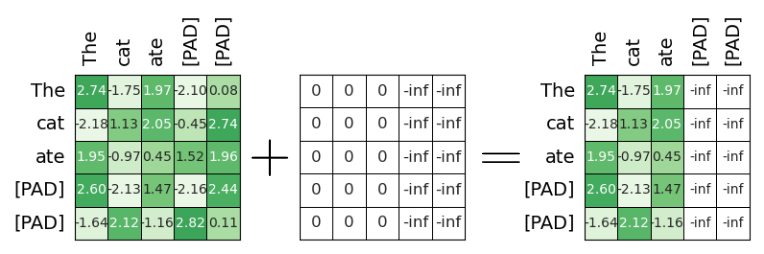

where $Q$, $K$, and $V$ contain word embedding vectors projected into the query, key, and value space. Since the padding token is also represented by some embedding vector, this vector also gets projected before the attention calculation. The figure below, shows the calculation of the attention scores $QK^T/d_k$ for the first sentence in the batch ("The cat ate [PAD] [PAD]"). The embedding vectors representing the padding token "[PAD]" are greyed out to indicate that these vectors do not carry any useful semantics. The resulting values of the attention score are just arbitrary for this purpose of this example.

The resulting matrix $A^{(0)}_{scores}$ containing the attention scores is of size $L\times L$ with respect to the first sequence, where $L$ is the length of the sequences in the batch (with or without padding). However, $A^{(0)}_{scores}$ contains scores that we want to ignore. More specifically, we want to ignore all attention scores that are the result of a dot product that involved at least one vectors representing padding token "[PAD]". Thus, intuitively, we seem to want an attention mask $A^{(0)}_{pad}$ that looks as follows:

While this mask could be used in practice, it turns out — and we will provide the reason for this later — that we only need to capture the padding tokens in the columns. This means that we typically use the following attention mask for our example sentence "The cat ate [PAD] [PAD]":

Before we continue and actually apply the mask, let's see how we could actually implement the calculation of the mask. For this, we first define the auxiliary method create_padding_mask() which creates a tensor of the same shape as the input batch but with $0$s at positions of non-padding words in the batch and with $-\infty$ at padded positions.

def create_padding_mask(batch, pad_value=PAD_IDX):

mask = (batch == pad_value)

mask = mask.float().masked_fill(mask == 1, float('-inf'))

return mask

Let's apply this method to our example batch.

padding_mask = create_padding_mask(batch)

print(padding_mask)

tensor([[0., 0., 0., -inf, -inf],

[0., 0., 0., 0., 0.],

[0., 0., 0., 0., -inf]])

As expected this mask shows that, for example, the first sequences contains three proper words and two padding tokens, again reflecting the first sentence in the batch ("The cat ate [PAD] [PAD]"). In fact, this padding_mask tensor is typically the mask you would pass a Transformer implementation provided by a library, which handles all involved computations transparently under the hood.

Of course, you will have noticed that padding_mask does not look like $A_{pad}$ since the latter is the actual mask to be used as part of the attention mechanism.

A0_pad = padding_mask[0].repeat(batch.shape[1], 1)

print(A0_pad)

tensor([[0., 0., 0., -inf, -inf],

[0., 0., 0., -inf, -inf],

[0., 0., 0., -inf, -inf],

[0., 0., 0., -inf, -inf],

[0., 0., 0., -inf, -inf]])

Keep in mind that $A^{(0)}_{pad}$ only represents the attention mask with respect to the first sequence. Since our example batch contains three sequences we have three attention matrices $A^{(i)}_{pad}$ with $i\in \{0,1,2\}$, which are shown below.

This means the the full attention mask $A_{pad}$ is a tensor of size $B\times L\times L$, where $B$ is the batch size (here: $3$), containing all $A^{(i)}_{pad}$:

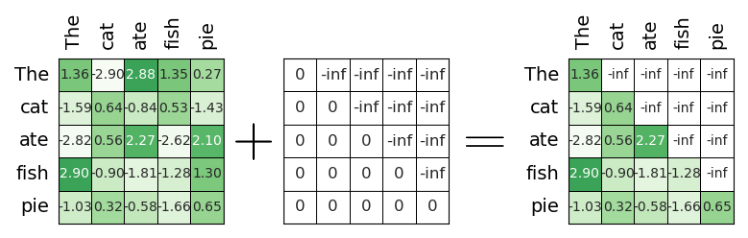

For simplicity, let's again focus on the attention mask $A^{(0)}_{pad}$ for the first sequence only. As before, applying a mask means adding the mask to the tensor with the attention scores, i.e., $A^{(0)}_{masked} = A^{(0)}_{scores} + A^{(0)}_{pad}$; the figure below illustrates this step.

Again, it might seem a bit strange that $A^{(0)}_{masked}$ contains some non-masked entries for attention scores involving thing the padding tokens "[PAD]". I minor and more pragmatic reason for this is that it won't cause any issues when calculating the actual attention weights using the softmax function. Recall that we applies the softmax to matrix $A^{(0)}_{masked}$ containing the attention scores to normalize the matrix so that all rows sum up to $1$. This is to ensure that the final matrix multiplication with $V$ yields output embedding vectors of the same magnitude as in input vectors.

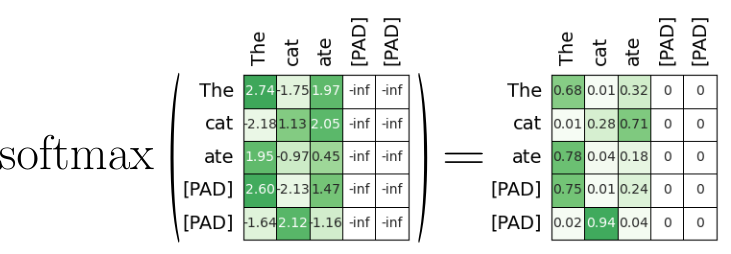

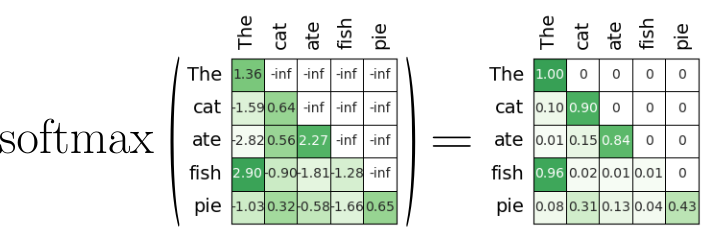

If the the last two rows in our matrix $A^{(0)}_{masked}$ would all be $-\infty$, the result of the softmax function would be undefined for both these rows — of course, in practice, we could handle this corner case by simply setting all values for those rows to $0$. However, since no row has only $-\infty$ values, we can can apply softmax without any special considerations. The figure below illustrations this operation; let $A^{(0)}_{weights}$ be the output matrix containing all attention weights — again, appreciate that all row values sum up to $1$:

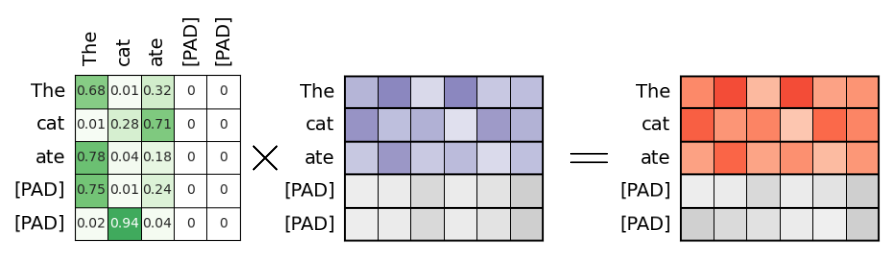

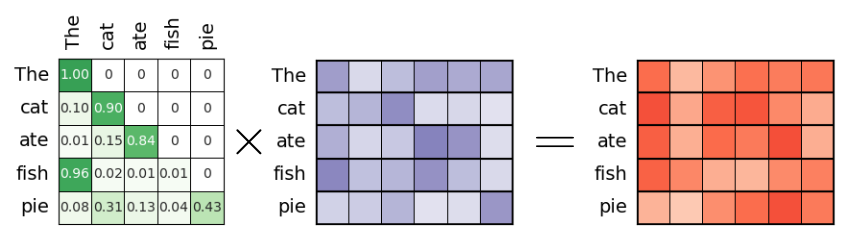

Thus, the last operation to calculate $Attention(Q,K,V)$ for the first sequence according to the formula (see above), is to multiply the attention weights matrix $A^{(0)}_{weights}$ with matrix $V$ containing the value vectors of the first sequence, i.e., $A^{(0)}_{weights}\times V$, as illustrated in the figure below. Again, the grey matrix cells in $A^{(0)}_{weights}$ and $V$ reflect the embedding vectors for the padding token.

Strictly speaking, we do update the embedding vectors of the padding token, and thus treat them like proper words. However, the important observation is that these padding embedding vectors never affect the attention scores of the proper words! For one, every subsequent transformer block with its own attention layer will equally ignore those vectors the same we just did in our worked example. And even after the last transformer block, although the final output will still contain "some" embedding vectors for each padding token, we will still apply loss masking to ignore those outputs.

Side note: It seems that we perform a lot of unnecessary computations by dragging the padding embedding vectors through all transformer blocks (including their attention layers). And in some sense, this is certainly true. However, recall why we introduced padding in the first place: to benefit from parallel processing (on GPUs) when working with batches instead of individual sequences. In other words, trying to minimize the total number of operations by treating each sequence individually, would again deprive us from the efficient use of GPU acceleration. It also keeps the required code much leaner.

Causal or Autoregressive Masking¶

The overall Transformer architecture has to main components: the encoder and the decoder. The common purpose of the decoder in the Transformer architecture is to generate sequences, typically in a step-by-step, autoregressive manner. In the context of text generation, this auto-regressive nature means that each generated token is conditioned on all previously generated tokens, ensuring coherence and grammatical correctness in the output. Essentially, the decoder acts as a powerful conditional language model.

Encoder-Decoder vs Decoder-Only¶

Transformer architectures use both encoder and decoder when the task requires understanding an input sequence and then generating a corresponding output — a common setup for sequence-to-sequence tasks. For example, in machine translation (e.g., translating English to French), the encoder processes the source sentence to capture its meaning, and the decoder generates the translated output. Architectures like the original Transformer from Vaswani et al. (2017) and T5 (Text-to-Text Transfer Transformer) use this encoder-decoder structure to handle such tasks effectively by separating input comprehension and output generation.

On the other hand, decoder-only architectures are used when the model's goal is to generate text based on a prompt or context, without requiring a separate encoded input. These models treat text generation as a language modeling problem, predicting the next word based on previous ones. Basically all popular Large Language Models (LLMs) — GPT (OpenAI), LLaMA (Meta), Gemini (Google), Claude (Anthropic), Mistral, etc, — are examples of decoder-only architectures. They are efficient for tasks like story generation, code completion, or question answering, where the context is part of the same sequence being generated rather than a separate input.

Independent from the exact architecture, the generation of sequences such as text requires the decoder. Let's first try to understand why we need a special masking strategy to facilitate autoregression (i.e., step-by-step) sequence generation.

Decoder: Inference vs Training¶

During inferencing, the decoder receives the first $t$ words $w_0, w_1, \dots, w_t$ as input to predict the next word $w_{t+1}$ at position $t+1$. In other words, the prediction of $w_{t+1}$ only depends on the previous words $w_0, w_1, \dots, w_t$. In the next step, $w_{t+1}$ is added to the sequence and the new sequence $w_0, w_1, \dots, w_t, w_{t+1}$ is given to the decoder to predict the next word $w_{t+2}$, and so on — until the decoder predicts an end-of-sequence token or some other stopping criteria is fulfilled (e.g., maximum sequence length).

During training, however, the decoder receives the complete sequence. And as for padding, without any considerations, the attention mechanism would compute all pairwise attention scores. This means that the output of the decoder at position $t$ would depend on all previous words as well as all subsequent words. In simple terms, during training, the decoder would be able to "look into the future". This we have to ensure that each word only attends to previous words but not to subsequent words. We can accomplish this once more through masking, more commonly called causal masking because the mask enforces a cause-and-effect relationship in the sequence: each token can only "see" (i.e., attend to) previous tokens, not future ones. This preserves the causal structure necessary for autoregressive generation, where each output depends only on what has come before — not what comes after.

Causal Masking: "Do not Look Ahead"¶

Let's go through a complete example by looking at the self-attention component of the Transformer decoder using our example sentence "The cat ate fish pie". We use this sentence here for a better illustration and to not be bothered by padding — in practice, padding masking and causal masking can be easily combined, though.

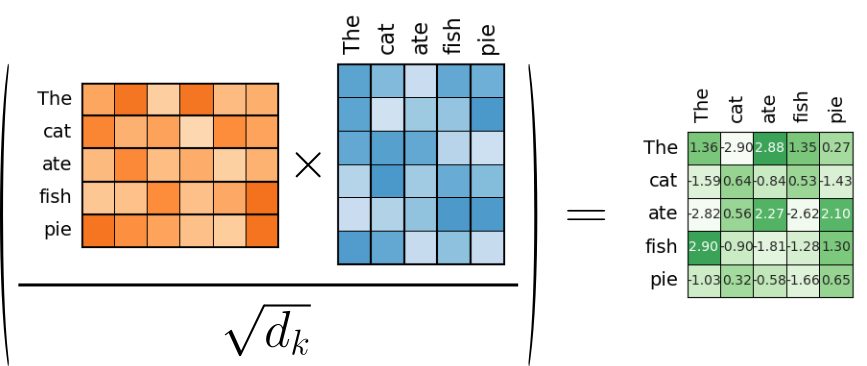

Like we have seen before, we assume that we have $Q$, $K$, and $V$ containing the word embedding vectors projected into the query, key, and value space to calculate $Attention(Q, K, V)$. To get the attention scores, we again first have to calculate $QK^T/d_k$. Let's denote the matrix with the attention scores as $A^{(1)}_{scores}$ since we now consider the sequence at position $1$ in our example batch.

$A^{(1)}_{scores}$ contains now all pairwise attention scores including the one between a word and all its subsequent words. We now have to ensure that each word $w_q$ in $Q$ ("orange matrix") only attends to words in $K$ ("blue matrix") that come before $w_q$ in the sequence. For example, if $w_q = \text{\textit{"}}ate\text{\textit{"}}$ we only want this word to attend to "The", "cat", and "ate" itself. Extending this restriction to all words in $Q$, what we need is therefore mask $A_{causal}$ that looks as follows:

Of course, like $A^{(1)}_{scores}$, the padding matrix $A_{causal}$ has a size of $L\times L$. Notice that $A_{causal}$ has no superscript since this mask is the same for all the sequences (with or without padding). Also, appreciate again, the diagonal is not masked out with $-\infty$ since each word can attend to itself.

Implementing this mask is also very straightforward using libraries such as PyTorch. First, we can use the full() method to create a tensor of a specified shape (here: $L\times L$) filled with a constant value (here: $-\infty$). Then, with the triu() method, we set all elements below a specified diagonal to zero. Since we do not want to mask the main diagonal, we need to set diagonal=1.

# Define L as the maximum sequence length in the batch

L = batch.shape[1]

# Create L x L tensors filled if -inf

A_causal = torch.full((L, L), float('-inf'))

# Set main diagonal and all entries below to 0

A_causal = torch.triu(A_causal, diagonal=1)

# Show causal matrix

print(A_causal)

tensor([[0., -inf, -inf, -inf, -inf],

[0., 0., -inf, -inf, -inf],

[0., 0., 0., -inf, -inf],

[0., 0., 0., 0., -inf],

[0., 0., 0., 0., 0.]])

Applying this causal mask just means to add the attention scores on the mask, i.e., $A^{(1)}_{masked} = A^{(1)}_{scores} + A_{causal}$, as illustrated in the figure below.

Once we have the masked attention scores $A^{(1)}_{masked}$, the rest of the attention calculation continues as usual. This requires next to apply the softmax function to $A^{(1)}_{masked}$ to yield the attention weights $A^{(1)}_{scores}$, with all row values in $A^{(1)}_{scores}$ summing up to $1$.

And the last step to get the final output of the attention mechanism is to multiply the attention weights $A^{(1)}_{scores}$ with the word embedding vectors in the value space represented by $V$. Given the figure below, it is easy to see that the output vector of, say, the word "ate" derives from the weights sum of the value vectors for "The", "cat", and "ate" itself — which was of course the whole purpose of applying the cause mask to the attention scores.

Causal masking during training ensures that the training mimics the autoregressive nature of the text generation task.

Important: Causal masking is also performed during inference, even if there are no obvious future words to attend to. This is required to ensure that inference is consistent with training. If causal masking were removed during inference, the model would be operating in a different mode than it was trained for, potentially leading to performance degradation.

Combining Padding and Causal Masking¶

To illustrate the idea of causal masking, we used the longest sequence in our example batch to avoid dealing with padding. However, combining padding and causal masking is very straightforward as it only requires adding the corresponding mask. For example, we can add padding mask $A^{(0)}_{pad}$ for the first sequence with the causal mask A_{causal} to get the final mask for the first sequence, assuming it serves as input for the decoder during training:

All the other steps of the attention calculation remain exactly the same.

Summary¶

Masking in sequence models refers to techniques used to control which parts of the input or output sequences are considered during training or inference. It plays a crucial role in ensuring that models handle sequences of variable lengths correctly, avoid learning from irrelevant data (like padding), and maintain the correct flow of information (such as preventing a token from attending to future tokens during generation). Masking is essential in both RNN-based and Transformer-based architectures, although the way it is implemented can differ significantly.

The first type, loss masking, is architecture-independent and is applied after the model’s forward pass. It is commonly used to ignore padding tokens in variable-length sequences during loss computation. For instance, when training on batches with padded sequences, loss masking ensures that the loss function only considers actual tokens (not padding) by applying a binary mask to the loss output. This helps the model focus its learning on meaningful parts of the data and is typically implemented by element-wise multiplying the loss with a mask tensor before computing the final loss value (e.g., via masked_loss = loss * mask).

In contrast, attention block masking is architecture-dependent and is particularly relevant in models that use attention mechanisms, like Transformers. This kind of masking modifies how tokens interact during self-attention. One example is causal masking — used in autoregressive models like GPT, LLaMA, Gemini, Claude, etc. — where each token is only allowed to attend to previous tokens to preserve the left-to-right nature of generation. Another example is padding masking, where attention scores to padded (irrelevant) tokens are masked out to prevent them from influencing the context representation. These masks are often added before the softmax in the attention mechanism to zero out or heavily down-weight unwanted attention.

In summary, masking in sequence models ensures correct and efficient training by handling variable sequence lengths and enforcing logical constraints on information flow. Loss masking operates independently of the model’s internals and focuses on making the loss computation accurate. Attention masking, however, requires deliberate design changes within the model's architecture and is crucial for guiding how attention is distributed across a sequence. Both are vital tools for building robust and effective sequence models.