Disclaimer: This Jupyter Notebook contains content generated with the assistance of AI. While every effort has been made to review and validate the outputs, users should independently verify critical information before relying on it. The SELENE notebook repository is constantly evolving. We recommend downloading or pulling the latest version of this notebook from Github.

Positional Encodings — Overview¶

Positional encodings (also positional embeddings) are a crucial component of the Transformer architecture, designed to inject information about the relative or absolute position of words in a sequence. Unlike recurrent neural networks (RNNs), which process words sequentially and inherently capture word order through their structure, Transformers process all words simultaneously (in parallel). This parallelism provides great efficiency but also means the model has no inherent sense of word order. To address this, positional encodings are vectors added to the input embeddings to give the model a sense of sequence order.

Common types of positional embeddings include sinusoidal positional encodings, learned positional embeddings, and more recent innovations like rotary positional embeddings (RoPE) and relative positional encodings. The sinusoidal encoding, used in the original Transformer, assigns each position a vector based on sine and cosine functions at different frequencies. These encodings are fixed and not learned, allowing the model to extrapolate to sequences longer than those seen during training. Learned positional embeddings, on the other hand, treat position information as learnable vectors, just like word embeddings. Each position in the sequence has a dedicated embedding vector that is optimized during training, providing flexibility and potentially better performance on in-distribution data.

Relative positional encodings and rotary positional embeddings take a different approach. Instead of encoding absolute positions, they encode the relative distances between words, which can be especially useful in tasks where relationships between words matter more than their absolute positions. Rotary embeddings (used in models like GPT-NeoX and LLaMA) integrate position into the self-attention mechanism by rotating query and key vectors based on their position, which improves the modeling of long-range dependencies and maintains efficiency.

What these methods have in common is the goal of giving the model a sense of order and position within sequences—critical for understanding language. Where they differ is in how they represent this order: fixed vs. learned, absolute vs. relative, or external addition vs. internal integration into attention computations. Each approach makes trade-offs between generalization, flexibility, and computational cost. In this notebook, we first look into the general concept and requirements for positional encodings, and then provide an overview of popular methods.

Setting up the Notebook¶

Make Required Imports¶

This notebook requires the import of different Python packages but also additional Python modules that are part of the repository. If a package is missing, use your preferred package manager (e.g., conda or pip) to install it. If the code cell below runs with any errors, all required packages and modules have successfully been imported.

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

Preliminaries¶

Before delving into the inner works of attention and multi-head attention, there are a few preliminary comments to outline the scope of this notebook:

- Since we focus on the original Transformer, we assume text as input. To make all visualizations, examples, and descriptions easier to understand, we assume that any input text is tokenized into proper words. Note that practical Transformer-based models typically rely on subword-based tokenizers (e.g., Byte-Pair Encoding, WordPiece).

With these clarifications out of the way, let's get started...

Positional Encodings: Basic Idea & Requirements¶

Motivation¶

Basically all of the roughly 7,000 spoken languages in the world today show some sensitivity to word order, but the degree to which it matters varies greatly depending on the language's grammar and structure. According to the World Atlas of Language Structures (WALS), about 80% of languages often rely on word order to clearly understand the meaning of a sentence. As a consequence, it is crucial for machine learning models to capture word order since the order of the words in a sentence directly affects its meaning. In English, for example, "The dog chased the cat" and "The cat chased the dog" use the same words, but the meaning changes completely based on the order. A model that ignores word order would treat both sentences as having the same meaning, which would lead to serious errors in tasks like translation, summarization, or sentiment analysis.

Word order also helps models understand grammatical structure — identifying subjects, verbs, and objects. For instance, in the sentence "She gave the book to her brother", switching the word order to "Her brother gave the book to she" not only changes the meaning but also introduces grammatical errors. Machine learning models, especially deep learning architectures like Recurrent Neural Networks RNNs and Transformers, are designed to learn these patterns so they can accurately capture relationships between words. Without an understanding of order, a model might misinterpret who is doing what to whom, leading to incorrect outputs across many natural language processing tasks.

Side note: There are some machine learning tasks involving text where word order matters very little or not at all, especially when the goal is to analyze content in a bag-of-words fashion. A good example is document classification based on topic. For instance, if you're training a model to classify news articles into categories like sports, politics, or technology, the presence of key words like "election", "vote", "parliament" or "football", "goal", "team" might be more important than the exact sequence they appear in. In such tasks, models like Naive Bayes or simple TF-IDF + Logistic Regression often perform well without considering word order. In short, when the overall content or word presence is more informative than sentence structure — such as in topic classification, spam filtering, or keyword spotting — models can afford to ignore word order and still perform effectively.

RNNs intrinsically capture word order because they process text sequentially — one word at a time — maintaining a hidden state that is updated at each step. This means that as each word is read, the RNN updates its internal memory based on both the current word and everything it has seen before. For example, when processing the sentence "The dog chased the cat", the RNN starts with "The", then updates its state with "dog", and continues through the sentence. This sequential processing naturally captures the temporal order of the words, allowing the model to learn dependencies that are sensitive to word positioning.

However, a major disadvantage of the sequential processing in RNNs is that it makes it difficult for the model to capture long-range dependencies in text. As RNNs read one word at a time and update their hidden state step by step, information from earlier in the sequence can fade or be overwritten as the text progresses. This problem, known as the vanishing gradient problem, means that RNNs often struggle to remember important details from the beginning of a long text by the time they reach the end. Additionally, because RNNs process text word-by-word, they are inherently slower to train and infer compared to models that can process data in parallel. This sequential nature limits their scalability, especially with long documents or when deployed in real-time applications.

In contrast, the Transformer architecture offers several key advantages over RNNs, particularly in terms of parallelism and long-range dependency modeling. Transformers use self-attention mechanisms that allow the model to consider all words in a sentence simultaneously. This means Transformers can process entire sequences in parallel, significantly speeding up both training and inference. This parallelism makes them much more efficient and scalable, especially when dealing with large datasets or long texts. Another major advantage is the Transformer's ability to capture long-range dependencies more effectively. While RNNs struggle to retain information across long sequences due to vanishing gradients, Transformers use attention layers that can directly link any word to any other word in the input, regardless of their position — including the distance between words in a text.

However, the Transformer architecture does not intrinsically capture word order because, unlike RNNs, it does not process text sequentially. The attention mechanism treats the input as a set of words without any built-in sense of sequence. In self-attention, each word attends to all other words in the input simultaneously, but this mechanism alone doesn't distinguish whether a word came earlier or later in the sentence. As a result, without additional information, a Transformer has no way to know the position of each word in the sequence.

To overcome this, Transformers use positional encodings (also positional embeddings). Positional encodings are vectors that are added to the input embeddings to inject information about each word's position in the sequence. These encodings can be learned or based on fixed mathematical patterns and help the model understand the position of each word. By combining these positional encodings with the word embeddings, the Transformer gains awareness of word order, allowing it to interpret sequences meaningfully. In essence, while the Transformer architecture is powerful in capturing relationships between words, it requires explicit positional information to understand sequence structure. There are generally two fundamental approach towards positional encodings:

Absolute positional encodings: Absolute positional encodings assign each position a unique vector, which is added to the corresponding word embedding. These vectors can either be fixed (i.e., calculated by a predefined formula depending on the position) are learned during training together with the rest of the model.

Relative positional encodings: Relative positional encodings represent the positions of words not by their absolute location in a sequence, but by their positions relative to one another. Instead of assigning a unique vector to each position (as in absolute encoding), this method encodes the distance or offset between pairs of words. Relative positional encodings are always learned.

Beyond methods that fall in exactly one of these two basic approaches, there are methods such as Rotary Positional Encodings (RoPE) that combine both absolute and relative positional information. In the rest of this notebook, we give an overview to absolute and relative positional encodings, and outline their strengths and weaknesses.

Basic Requirements¶

With positional encodings being "some vectors" capturing positional embeddings that are added to the embedding vectors of words (i.e., encodings capturing the meaning of words), the obvious questions what kind of vectors represent meaningful positional encodings and how do we get them. Before we cover some of the more common methods, let's first derive some basic characteristics positional encodings need to have. We can do this by looking at some naive approaches and discussing the problems and limitations. We use absolute positional encoding for this since it is generally the simpler approach.

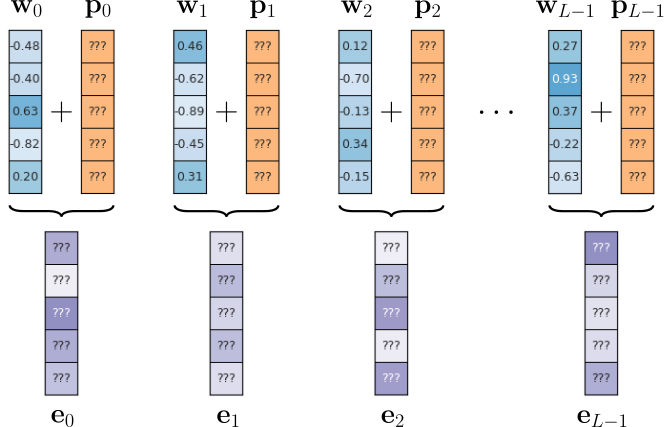

The figure below shows the most basic idea behind absolute positional encodings. In this figure, $\mathbf{w}_i$ represents the embedding vector of the word at the $i$-th position in the input sequence of length $L$; $\mathbf{p}_i$ is an embedding vector encoding position $i$ which is added to word embedding vector $\mathbf{w}_i$, forming the combined embedding vector $\mathbf{e}_i$. All resulting vectors $\mathbf{e}_{0}, \mathbf{e}_{1}, \mathbf{e}_{2}, ..., \mathbf{e}_{L\!-\!1}$ then form the input sequence for the Transformer model.

Of course, we now need to find values for the positional encoding vectors $\mathbf{p}_{0}, \mathbf{p}_{1}, \mathbf{p}_{2}, ..., \mathbf{p}_{L\!-\!1}$

Naive Methods¶

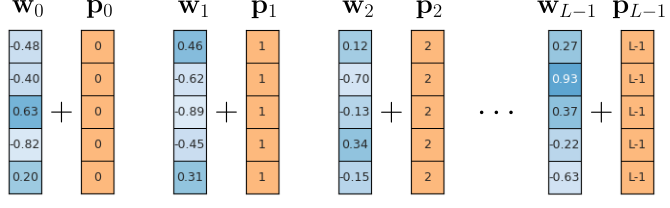

The arguably most straightforward way to define the positional embedding vectors is to set all elements in the vector for encoding position $i$ to $i$ itself — that is, $\mathbf{p}_{ij} = i$, where $\mathbf{p}_{ij}$ is the $j$-th vector element of the positional embedding vector at position $i$. The figure below illustrates this method.

These positional embedding vectors are suitable to the extent that they are unique. In other words, each position is represented by its own unique vector and there are no two positions encoded by the same embedding vector. However, notice that the absolute size of the values in the embedding vectors depends on the sequence length $L$. This means that for long(er) sequences, the positional encodings become larger and larger vectors. For example, for $L=100$ this means that $\mathbf{p}_{100} = [100, 100, 100, \dots, 100]^T$. Assuming that word embedding vectors are typically normalized (e.g., into the range $-1$ to $+1$ like shown in the example), the positional encodings $\mathbf{p}_{i}$ quickly start to dominate the final embedding vectors $\mathbf{e}_{i}$, more and more obfuscating the semantic information captured by the word embedding vectors $\mathbf{w}_{i}$.

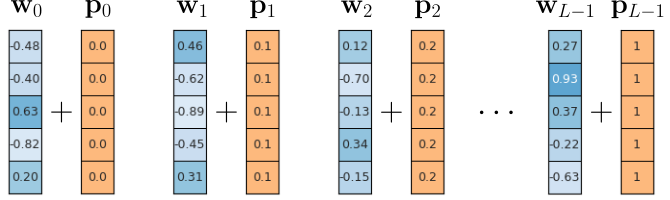

Since unbound embeddings are likely to cause problems in practice, we can try forcing them into a fixed range using normalization. For example, we can ensure that all positional embedding vectors using the previous approach are between $0$ and $+1$ by calculating $\mathbf{p}_{ij} = i/(L-1)$; see the figure below illustrating this normalization attempt.

What we gained with this method is that the positional embeddings vectors no longer run the risk of dominating the word embedding vectors. Simply speaking, the values in the positional encodings are guaranteed to remain small. However, because the values do not depend on the sequence length $L$, the encodings are no longer unique. This means that the vector $\mathbf{p}_i$ will be different for two sequences that do not have the same length. However, in case of absolute positional encodings, $\mathbf{p}_{i}$ should always be the same vector encoding position $i$.

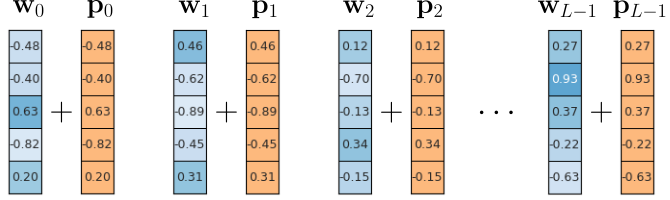

Lastly, let's consider the alternative where we set the values of the positional embedding vectors randomly, e.g. from a uniform distribution: $\mathbf{p}_{ij} \sim U(-1, +1)$; see the example in the figure below.

Now all vectors $\mathbf{p}_{i}$ are unique but also guaranteed to be small. However, random vectors are unlikely to capture any systematic relationship between different positions. This means the model cannot learn patterns based on word order, such as the fact that position 3 comes after position 2 or is close to position 4. Also such vectors also fail to generalize to longer sequences. This is an issue in practice because models are trained with some fixed maximum input length, causing issues when working with longer inputs after training — we illustrate this in more detail when discussing the limitation of absolute positional encodings. Random vectors, being uncorrelated and fixed, offer no such continuity or pattern, so the model struggles with sequences longer than those seen during training.

Note that the first issue of not capturing any systematic relationships between positions can be alleviated if the positional embedding vectors are not fixed but are learnable during the training process. In other words, the model now can learn relevant patterns to capture relationships between positions. Of course, this approach will increase the overall training time. It has also been shown that "smart" fixed absolute encodings perform equally well as learned encodings.

Summary¶

Even from the simple examples shown above, we can see that there are better and worse ways to encode positional information using embedding vectors. While some requirements for positional encodings stem from the exact use case or domain (e.g., text, images, graphs), there is a set of general characteristics that good positional encodings should have:

Uniqueness and consistency: Each individual positional information — either an absolute position or a relative position — needs to be represented by a unique embedding vector. For example, in case of absolute positions, two positions should not be represented by the same vector. These vectors also need to be consistent, which means they should be the same for different sequence lengths.

Order sensitivity: Positional encodings must capture relative and/or absolute order of words — this is why we introduce positional encodings after all. Particularly for text data and tasks like natural language understanding, good encodings have the ability to capture relative information. Even if absolute positions are used, the encoding scheme should implicitly or explicitly allow the model to infer relative distances between words.

Extrapolability: Most Transformer models are trained using input sequences of some predefined maximum length. During inference, however, the model may receive longer sequences as inputs. A robust positional encoding scheme should be able to generalize to sequences longer than those encountered during training. This is critical for real-world applications where input lengths can vary significantly.

"Small" values: The values of the positional embeddings vectors should be small so they do not dominate the semantic information captured by the word embedding vectors. This requirement is typically trivial to satisfy.

Scalability: The encoding method should be computationally efficient, especially for very long sequences or large datasets.

Note that there is arguably no perfect encoding method that is guaranteed to work best for all cases since all methods have different strengths and weaknesses with respect to the proposed set of requirements. We will highlight some of those strengths and weaknesses when covering some of the basic approaches for positional encodings.

Absolute vs Relative Positional Encodings¶

In Transformer-based models, two primary strategies for positional encodings have emerged: absolute and relative positional encodings. Absolute positional encodings assign a unique position vector to each word based on its location in the sequence. These encodings, whether fixed (like sinusoidal functions) or learned, help the model distinguish between words at different positions by explicitly encoding their absolute indices.

In contrast, relative positional encodings focus on capturing the distance or offset between words, enabling the model to understand their contextual relationships regardless of their absolute position in the sequence. This approach is especially useful for modeling long-range dependencies and for tasks where relative structure is more meaningful than exact position. Each method has its strengths: absolute encodings provide global position awareness, while relative encodings offer flexibility and improved generalization in contexts with variable-length inputs.

Let's look at both strategies in more detail.

Absolute Positional Encodings (APEs)¶

As the name suggests, absolute positional encodings (APEs) assign each position in the input sequence is assigned a unique encoding, typically a fixed vector. These encodings are added to the words embeddings before being fed into the transformer layers, allowing the model to distinguish between positions in the input. APEs encode positions independently of the context — they assign a static vector to each position (e.g., position 0, position 1, etc.) regardless of the surrounding words. The figure below illustrates this idea; for simplicity we assume that the maximum length of a sequence, i.e., the maximum size of the context window, is $L=10$.

When $L=0$, requires (at least) $L$ unique embedding vectors to encode each position. These vectores can either be learned as well as fixed — that is, calculated by some predefined function(s). Let's have a closer look at and compare both approaches.

Learned APEs¶

Learned APEs are very similar to learning word embeddings. Recall that a word encoding/embedding maps discrete word indices into continuous embedding vectors using a weight matrix $W_w$, typically called the embedding matrix. This matrix has a shape of $V\times D_w$, where $V$ is the vocabulary size and $D_w$ is the desired embedding dimension (e.g., 300). Each row of the matrix corresponds to a word in the vocabulary, and the row values represent the learned embedding vector for that word. When a word is input as an index (say, from a tokenized sentence), that index is used to select the corresponding row in the embedding matrix. This process is essentially a lookup operation: the model retrieves the row of weights corresponding to the input word index, giving its dense vector representation. During training, these embedding vectors (i.e., the weight matrix rows) are updated to capture semantic relationships between words based on their context in the training data.

For encoding the absolute position of words, we can define a weight matrix $W_p$ that maps the discrete word positions $0$, $1$, $2$, ..., $L-1$ continuous embedding vectors as well. This weight matrix $W_p$ has a shape of $L\times D_p$, where $L$ is the maximum sequence length used during training and $D_p$ is the desired embedding dimensions. Here, each row in $W_p$ represents a position, the row values represent the learned embedding vector for that position. In practice, the size of positional embeddings is typically the same as for the word embeddings, i.e, $D_p = D_w$, so that both resulting vectors can directly be added to form the final embedding vector. Given an input sequence of length $l$ the model retrieves the rows from matrix $W_p$ that correspond to the vector representations for all positions $0$, $1$, $2$, ..., $l-1$. Like the word embeddings, the positional embeddings are updated during training.

To give a practical example, let's look at a basic implementation of a positional embedding as its own PyTorch module. The class LearnedAPE in the code cell below implements a simple PyTorch module containing only one layer of type nn.Embedding to facilitate the lookup of positions to their respective vectors. In the forward() method, we assume that we get a tensor of shape $(batch\_size, seq\_len)$ as input, where seq_len is the length of all sequences in that batch. This we can first create an 1d auxiliary tensor

which then serves as input for the embedding layer self.embedding.

class LearnedAPE(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, max_seq_len, embed_size):

super().__init__()

# Embedding layer for position vectors

self.embedding = nn.Embedding(max_seq_len, embed_size)

def forward(self, x): # x.shape = (batch_size, seq_len)

# Create vector position up to seq_len: [0, 1, 2, ..., seq_len]

positions = torch.arange(0, x.shape[1], dtype=torch.long)

# Push position vector through embedding layer and return result

return self.embedding(positions)

The output of this layer (i.e., PyTorch module) will be a tensor with shape $(batch\_size, embed\_dim)$ containing the positional embedding vectors for each word in each sequence. Note that is a rather straightforward naive implementation, just to illustrate the idea. Since the positional embedding vector do not depend on the actual words, each sequence of the input batch will return the same sequence of positional embedding vectors. In other words, the output contains the same vectors $batch\_size$ times. While this can be optimized in practice, it does allow for direct use in any model.

The code cell below shows a code snippet focusing only on the use of the LearnedAPE class in a complete model. This model has two embedding layers The one for the word embedding vectores uses an nn.Embedding layer since it directly receives the word indices from an input batch. The embedding layer for the positional embedding vectors uses the LearnedAPI class as it handles the extraction from the position indices. In the forward() method, both word and position embedding vectors are extracted via lookup operations and combined by adding them for the final embedding vectors.

class ExampleModel(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, vocab_size, max_seq_len, word_embed_size, pos_embed_size):

super().__init__()

# Embedding layer for word vectord

self.word_embedding = nn.Embedding(vocab_size, word_embed_size)

# Embedding layer for position vectors

self.positional_embedding = LearnedAPE(max_seq_len, pos_embed_size)

# ...other layers and/ore model components...

def forward(self, x): # x.shape = (batch_size, seq_len)

# Get word and position embeddings

word_embeddings = self.word_embedding(x)

position_embeddings = self.position_embedding(x)

# Add tensors to get final embeddings

embeddings = word_embeddings + position_embeddings

# ...other processing steps...

While learned APE are an intuitive way to implement positional encodings, they are not commonly used in practice. For one, they naturally introduce additional parameters that need to be learned during training. Learning positional embeddings vectors is typically also not required since the basic requirements are that these vectors are unique, content-independent, and have small values. These requirements can also be met using fixed APEs. Learned APEs also have other limitations which we discuss in more detail when motivating relative positional encodings.

Fixed APEs¶

Fixed absolute positional encodings use a deterministic function; these encodings are fixed and not updated during training. When it comes to the requirements of unique and content-independent vectors with small value, the choice of possible functions is almost arbitrary. In fact, one could set the position embedding vectors even randomly.

However, random or more naive functions to generate APEs typically do not generalize well. Generalization, in the context of APEs, refers to a model's ability to handle input sequences of lengths or patterns that differ from those seen during training. For positional encodings, this means correctly understanding and processing words at positions beyond the original training set or in new contexts. Generalization is crucial for absolute positional encodings because language and many real-world data types are inherently variable in length. If a model is trained with learned encodings on fixed-length inputs, it may struggle or completely fail to interpret words at unseen positions during inference. This can severely limit the model's utility, particularly in applications like translation, document summarization, or code analysis, where inputs can be unpredictably long.

Common approaches for fixed APEs use the sine and cosine functions as they offer a smooth, continuous, and periodic way to represent positions in a sequence with a consistent structure. By encoding each position using sine and cosine waves of different frequencies, the model can distinguish between positions while also capturing relative distances in a mathematically meaningful way. This approach allows each position to be uniquely represented and ensures that the positional encoding space is smooth and generalizes well across different sequence lengths. For example, the original Transformer paper "Attention is all you Need" proposed the following set of functions:

where $\mathbf{p}_{ij}$ again represents the $j$-th entry/element of the positional embedding vector for position $i$. In other words, a single vector value not only depends on the position but also if the corresponding index of the vector is an even or odd index.

Other notebooks will cover this approach from the original Transformer paper as well as other implementations of fixed APEs in more detail.

Limitations of APEs¶

Particularly fixed APEs are easy to compute and require no training. Therefore no additional parameters need to be learned, which reduces the model's complexity. Each position in the sequence gets a distinct encoding in the form of a unique vector, allowing the model to identify absolute positions of words — important in tasks like sequence labeling or position-sensitive classification. However, absolute positional encodings also have several limitations:

Absolute vs. relative position. For many language understanding tasks (e.g., machine translation, questions answering, text summarization) the relative position between words is often more important than their absolute positions. While approaches such as sinusoidal encodings (see above) are theoretically able to infer relative positions, absolute positional encodings do not explicitly encode relative distances. This might force the model to work harder to learn these relationships, potentially leading to less efficient learning compared to strategies that directly incorporate relative positional biases. This may include that absolute positional encodings might provide an unnecessary strong signal for exact positions, potentially diverting attention from more crucial relative relationships.

Consider the following example from the paper The Curious Case of Absolute Position Embeddings:

- smoking kills (Positions 0-1)

- kim said smoking kills (Positions 2-3)

- it was commonly believed by most adult Americans in the 90s that smoking kills (Positions 12-13)

Arguably, the absolute position of the phrase smoking kills should be less important to capture the overall meaning — at least given these three example sentences which generally have the same stance about the effects of smoking. Of course, absolute positional encodings will add different positional embedding vectors in all three cases, and it is not obvious how this will affect the model to learn. In fact, the paper shows that the overemphasis on absolute positions can have negative effects on a model's performance.

Limited Generalization to Unseen Sequence Lengths (Extrapolation). At least in principle, fixed APE such as sinusoidal encodings as proposed in the original Transformer paper allow for the deterministic calculation of positional encodings for arbitrary positions. However, while mathematically well defined, the model itself may not have learned to effectively interpret the positional information for distances or absolute positions far outside its training distribution. The sinusoidal patterns might become less distinct at very large positions, making it harder for the model to differentiate between distant words accurately. The model's ability to generalize relies on learning patterns from the positional information it has seen, and extrapolating these patterns to much larger scales is not guaranteed.

Of course, this issue is even more pronounced for learned APEs as they do not provide any meaningful way to extrapolate to sequences longer than the sequences seen during training. Since fixed APEs also reduce a model's complexity by avoiding to learn any trainable parameters, fixed methods are typically the preferred choice when using absolute positional encodings — although certain domains or tasks might still perform better using learned APEs.

Relative Position Encodings (RPEs)¶

Relative positional embeddings are a technique used in transformer models to incorporate information about the positions of words in a sequence relative to one another, rather than their absolute positions. This contrasts with traditional absolute positional embeddings, which assign a fixed position to each word. Relative embeddings allow models to focus on the relative distances between words, which can be especially useful in tasks where meaning depends more on word-to-word relationships than on fixed positions within the sequence.

This approach has been shown to improve performance in various natural language processing tasks by providing greater flexibility and generalization, especially in handling variable-length inputs. It enhances the model's ability to recognize similar patterns regardless of their specific location in the sequence, which is particularly beneficial in settings like machine translation, document summarization, and long-context understanding — that is, tasks where the relationship between words reflected by there distance within a text is more important that their absolute distance in the sequence.

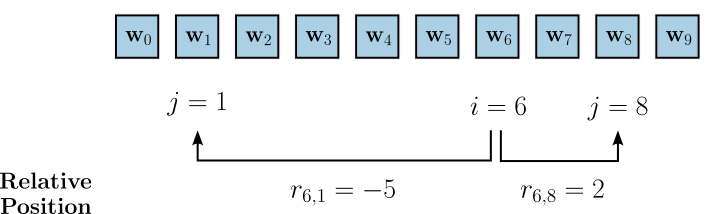

The figure below shows the same example sequence of length $L=10$ from before. However, this time it illustrate the relative position of word embeddings $\mathbf{w}_1$ and $\mathbf{w}_8$ with respect to the word embedding vector $\mathbf{w}_6$. We can define the relative position of a word at position $j$ with respect to a word at position $4$ as

with $r_{6,1} = 1-6 = 5$ and $r_{6,8} = 8-6 = 2$ as the two examples shown in the figure below.

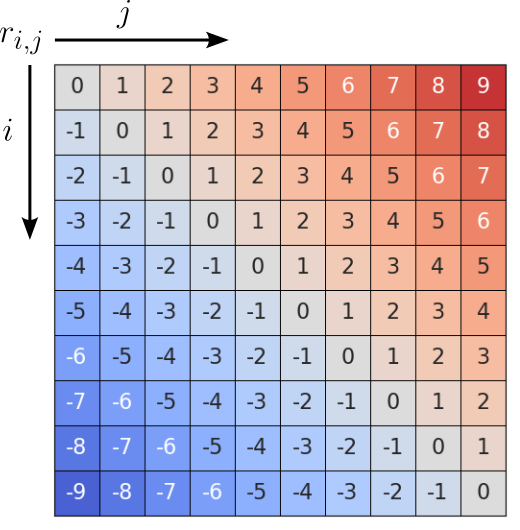

If we calculate the $r_{i,j}$ values for all combinations of $i$ and $j$ with $i,j \in [1, 2, ..., 9]$, we get a matrix $\mathbf{R}$ with shape $L\times L \times D_p$, where $D_p$ is again the size of the positional embedding vectors. The figure below shows the resulting matrix $\mathbf{R}$ for our example sequence; note that this illustration represents the embedding vectors only as a label reflecting the relative distance. For example, the entry $-5$ represents the positional embedding vector for the relative distance of $-5$ (e.g., including $r_{6,1}$).

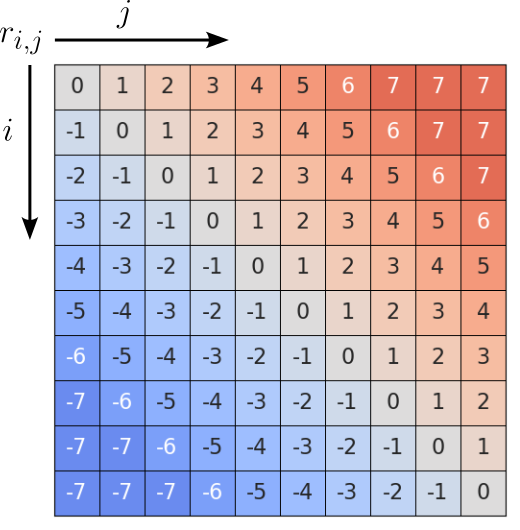

Although this matrix has $L^2$ entries, all entries with the same $r_{i,j}$ value represent the same positional encoding; we denote the actual embedding vector as $\mathbf{r}_{i,j}$. Thus, we do not have to capture $L^2$ positional encoding vectors but only $2L - 1$ vectors, as this is the number of unique values in $\mathbf{R}$. Practical implementation of relative positional encodings often implement clipping, i.e., limiting the maximum distance $k$ between words to be captured. The intuition is that at some point it does not really matter if two words are far or very far apart particularly in very long sequences. The figure below shows the same matrix from before but now after clipping with $k=7$; this means that the largest value in the matrix is now $7$.

As a result, the number of unique positional encodings required is now $2k-1$, with $k < L$. Reducing the total number of required encodings in a meaningful way is useful in practice since relative positional encodings are usually learned and not fixed.

In contrast to absolute positional encodings, a vector $\mathbf{r}_{i,j}$ representing a relative positional encoding is no longer associated with a single word but with a pair of words. As such, we can no longer simply add $\mathbf{p}_{i,j}$ to a word embedding vector $\mathbf{w}_{i}$ or $\mathbf{w}_{j}$ before feeding the combined embedding vector into the Transformer. Relative positional encodings are therefore integrated into the attention mechanism of the Transformer itself. On its own, the attention mechanism aims to capture the relationship between word pairs based on their word embeddings — strictly speaking between their projected embeddings into the query, key, and value space. How this is done in detail depends on the exact method and implementation which is beyond the scope here and will be covered in other notebooks. The key take-away message here is that using relative positional encodings combine the pairwise relationship between words with the pairwise relationship between their positions, with both types of relationships learned during training.

Comparison¶

Just by covering the basic ideas and method behind absolute and relation positional encodings — and without looking into concrete implementations — we can see that both approaches are fundamentally quite different. The table below summarizes their key differences.

| Feature | Absolute Positional Encodings | Relative Positional Encodings |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Assigns a unique embedding to each absolute position in the sequence | Encodes the relative distance between words |

| Position Referencing | Refers to the word's position in the entire sequence | Refers to how far one word is from another |

| Learning Type | Can be fixed (e.g., sinusoidal) or learned | Usually learned |

| Sequence generalization | Fixed types (e.g., sinusoidal) can extrapolate to longer sequences but effectiveness not very clear | Can generalize better across sequence lengths |

| Sensitivity to word shifts | Sensitive — shifting words changes their positional meaning | More robust — only relative distances matter |

| Use in attention mechanism | Position is added to the word embedding and used directly | Position modifies attention scores between word pairs |

| Implementation Complexity | Simple to implement | More complex — requires modification to attention mechanism |

| Context Awareness | Encodes position absolutely, without regard to neighboring words | Better captures local context through relative distances |

| Examples of Use | Original Transformer (Vaswani et al., 2017) | Transformer-XL, T5, DeBERTa, GPT-NeoX |

As mentioned before, there is arguably no single best approach that should always be preferred. The main deciding factor is if a given task is likely to benefit more from explicitly capturing the absolute position of words (e.g., syntactic parsing, simple sentence classification, time series forecasting with fixed lags/features) or the relative position of words (e.g., machine translation, text summarization, question answering, language modelling). Also, there are also encoding methods that combine concepts from absolute and relative positional encodings to combine their strengths (see below).

Discussion — What's Next?¶

In this notebook, we motivated the need for positional encodings for Transformer models, since they (generally) do not provide a built-in capacity to capture word order (assuming text as input). We then focused on the two main strategies for implementing positional encodings: absolute and relative positional encodings. However, a more detailed introduction to popular encoding methods is subject to dedicated notebooks. Apart from that, the topic of positional encodings includes further considerations.

Alternative Encoding Strategies¶

Beyond the common absolute and relative positional encoding methods, other alternative strategies are continued to be explored, often utilizing more sophisticated ways to inject sequence order information into Transformer models. These methods often aim to improve generalization to longer sequences, reduce computational overhead, or better capture specific types of positional dependencies. Notable examples include:

Rotary Positional Embeddings (RoPE): Instead of directly adding or biasing attention scores, RoPE applies a rotation to the query and key vectors in the self-attention mechanism. This rotation is dependent on the token's position, and when two rotated vectors are dot-producted, the result implicitly encodes their relative distance. RoPE has excellent theoretical properties, including the ability to generalize to arbitrary sequence lengths and a natural decaying inter-token dependency with increasing relative distances. It has become a very popular choice in many large language models (LLMs) like Llama.

Attention with Linear Biases (ALiBi): ALiBi entirely dispenses with explicit position embeddings. Instead, it directly modifies the attention scores (pre-softmax logits) by adding a linear bias that is proportional to the distance between the query and key tokens. This bias is negative and grows with distance, effectively penalizing attention to distant tokens. Each attention head can have a different slope for this linear bias. ALiBi has shown strong extrapolation capabilities to sequences much longer than those seen during training, making it attractive for training efficient LLMs.

Learnable Positional Encodings (Beyond Simple Addition): While the original Transformer used fixed sinusoidal absolute positional encodings, many subsequent models (like BERT) adopted learnable absolute positional embeddings. However, this is distinct from methods that learn how positional information is integrated or transformed. Some approaches propose learning the positional encoding function itself, or using small MLPs to generate biases based on relative distances, allowing for more flexible and adaptive encoding. Examples include FIRE (Functional Interpolation for Relative Positional Encoding) which learns biases via an MLP, unifying and generalizing over other RPEs.

Convolution-based Positional Encodings (CPEs): CPEs attempt to leverage Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) to enhance the positional understanding of Transformers. CNNs are designed with local receptive fields and weight sharing, making them excellent at extracting local features and recognizing patterns that are spatially invariant. The core idea behind convolution-based positional encodings is to use convolutional layers to generate or modify positional information, often by processing the input embeddings or learned positional embeddings. While not a drop-in replacement for all transformer tasks, they can be particularly effective in hybrid models, multimodal applications, and tasks emphasizing local structure, and serve as a compelling alternative to traditional positional embeddings.

No Positional Encoding (NoPE): Surprisingly, some research suggests that in certain decoder-only Transformer setups (like GPT-style LLMs), and especially for length generalization, explicit positional encodings might not be strictly necessary, or that simpler implicit mechanisms are at play. While this is a more controversial area, it highlights that the causal masking itself in decoder-only models already introduces some form of positional information. However, empirical studies often show that with proper positional encoding, performance and generalization are significantly better.

These methods represent a continuous effort to improve how Transformers handle sequential data, offering different trade-offs in terms of computational efficiency, generalization, and interpretability. RoPE and ALiBi, in particular, have gained significant traction due to their ability to enable models to process much longer contexts than they were trained on. Other notebooks will cover concrete encoding methods in much greater detail.

Modifying Word Embeddings: Any Harm?¶

We saw that incorporating positional encodings comes down to adding positional embedding vectors to the word embedding vectors — either to the initial word embeddings or to the query, key, or values vectors as part of the attention mechanisms. However, it is not obvious why this is a good idea. After all, word embeddings are supposed to capture the semantic meanings of words which are now potentially modified by the positional encodings. In practice, this does generally not cause any issue for two main reasons:

Only minor changes: Recall that we assume that positional ecodings do not feature values that dominate the values in the word embedding vectors. This means that the changes to the word embedding vectors by adding the positional encodings are generally small and are unlikely to fundamentally change the meaning of the word as captured by its word embedding. The idea is that this perturbation shifts the word's embedding vector slightly in the embedding space based on its position, but crucially, it does so in a way that the original semantic information of the word is largely preserved. It's like adding a small, consistent "directional signal" to each word's base meaning.

High-dimensional and orthogonal embedding subspaces: Word embeddings — and therefore positional embeddings — live in high-dimensional spaces (e.g., 768, 1024, 2048 dimensions). In high-dimensional spaces, randomly chosen vectors tend to be approximately orthogonal. This means that their dot product, which measures the angle between them, is often very small, approaching zero. In general, there is no reason to assume that the word vectors and position encoding vectors are related in any way. If the word embeddings form a smaller dimensional subspace and the positional encodings form another smaller dimensional subspace, it is very likely that these two subspaces themselves are approximately orthogonal, so presumably these subspaces can be transformed almost independently through the same transformations. This in turn allows the Transformer model to learn to disentangle these combined features.

That being said, different encoding methods show different performances for different tasks, and due to the models' complexities, it is not always straightforward to pinpoint the causes for certain (good or bad) behaviors. For example, there is not obvious rule that states when positional encodings are "large enough" to have a meaningful effect but also "small enough" to not modify the word embedding vectors too much.

Summary¶

Positional embeddings are a critical component in transformer architectures, which, unlike recurrent neural networks (RNNs), process sequences in parallel and thus lack an inherent notion of order. To capture the sequential nature of input data — such as the order of words in a sentence — transformers require an additional mechanism to provide position-related information. Positional embeddings serve this role by injecting information about the positions of tokens into the model, enabling it to learn order-dependent representations.

The two most common approaches to positional encoding are absolute and relative positional embeddings. Absolute positional embeddings assign each position in the input sequence a unique vector, often using sinusoidal functions or learned embeddings. These encodings are added to the token embeddings and are fixed across different sequences, giving the model a global sense of position. This method works well in tasks where the position of a token in the sequence carries semantic importance, such as in autoregressive language modeling or structured data generation.

Relative positional embeddings, in contrast, focus on the distance between tokens rather than their fixed locations in a sequence. This approach allows the model to consider how close or far apart two tokens are, regardless of their absolute positions. This is particularly effective for tasks where local context and token-to-token relationships matter more than their global positions — such as machine translation or document-level question answering — leading to improved generalization and robustness, especially with variable-length inputs.

Beyond these two, alternative strategies have also emerged. Some models use rotary positional encodings (RoPE), which encode positions through rotation in the embedding space, enabling more efficient and scalable modeling of relative positions. Others integrate convolutional layers, attention biases, or even learned recurrence to capture sequential patterns.

In summary, positional embeddings are essential for enabling transformers to understand sequence order. Absolute encodings provide a global position reference, while relative encodings emphasize inter-token distances, with each approach suiting different task types. As the field advances, hybrid and novel methods continue to push the boundaries of how positional information can be effectively modeled.