Disclaimer: This Jupyter Notebook contains content generated with the assistance of AI. While every effort has been made to review and validate the outputs, users should independently verify critical information before relying on it. The SELENE notebook repository is constantly evolving. We recommend downloading or pulling the latest version of this notebook from Github.

Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) — Basics¶

Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) is an AI framework that enhances the output of Large Language Models (LLMs) by giving them access to external, up-to-date, and authoritative knowledge sources before generating a response. Instead of relying solely on the static, potentially outdated knowledge contained in their training data, a RAG system first retrieves relevant documents or data snippets from a specified knowledge base (like a company's internal documents, a specialized database, or the live web). This retrieved information is then provided as additional context, or "augmentation", to the LLM alongside the user's initial prompt, guiding the model to generate a more grounded, accurate, and relevant answer. This process essentially turns the LLM's task into an "open-book" exam, rather than a "closed-book" one, significantly improving the quality of its output.

RAG is needed and incredibly useful for many applications because it directly addresses key limitations of standard LLMs. A major issue is the knowledge cutoff: an LLM's internal knowledge is limited to the data it was trained on, which means it can't answer questions about recent events or proprietary, domain-specific information (e.g., a company's newest product manual or current stock prices). Furthermore, LLMs can sometimes "hallucinate", producing confidently stated but factually incorrect or nonsensical information. RAG mitigates these problems by ensuring the response is factually grounded in verified external data. This provides current and domain-specific information without the massive computational cost and time required to constantly retrain the entire LLM. It also enables source attribution, allowing users to verify the information and increasing trust in the AI system.

It is important to learn about RAG because it has rapidly become the industry-standard architecture for deploying LLMs into real-world, enterprise-level applications. For anyone working with generative AI—from developers and data scientists to product managers—understanding RAG is essential for building practical, scalable, and trustworthy solutions. RAG is the foundation for creating sophisticated, custom AI agents, chatbots, and knowledge management systems that can intelligently interact with private, constantly evolving data. Its focus on accuracy, auditability, and cost-efficiency makes it a cornerstone technology for the next wave of AI products, making knowledge of RAG a critical and highly sought-after skill in the modern technology landscape.

Setting up the Notebook¶

This notebook does not contain any code, so there is no need to import any libraries.

Motivation & Overview¶

Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) has become very popular because it (a) addresses a fundamental limitation of LLMs, and (b) offers a rather powerful, flexible, and relatively cost-effective solution. Let's elaborate on this a bit more by looking at the two questions: why do we use RAG and how does it work in a nutshell?

Why RAG?¶

Large language models (LLMs) have become powerful, but they face several limitations that affect their usefulness in practical applications. One of the biggest limitations is their fixed knowledge cutoff: LLMs can generate responses based on what they saw and learned during training. Most obviously, this cutoff includes any kind of knowledge or data generated after the training. This is a particular concern for fast-changing domains like current events (i.e., news), stock markets, or scientific research. Also LLMs are (hopefully) not training using non-public and potentially sensitive data (e.g., company data, healthcare data, personal information). Thus a company cannot use a pretrained LLM "as is" to make its internal data accessible and searchable using natural language — a very common target application for LLMs!

When questions go beyond an LLM's knowledge cutoff, the model cannot truly access or "know" the proper answer. However, since LLMs generate text based on statistical patterns rather than explicit fact-checking, that falls back on patterns learned from training data to still reply with something. This can lead to several problematic behaviors, mainly:

Hallucination of plausible answers: The model may generate a confident-sounding response by extrapolating from older patterns, even if the information is outdated or entirely fabricated. For example, if asked about a political leader elected after the cutoff date, the model might wrongly guess based on past candidates or trends.

Generic or vague responses: Sometimes the model hedges by giving broad or timeless information instead of a concrete answer. For instance, it might describe "how elections generally work" instead of naming a specific winner it hasn’t seen in training.

Inability to acknowledge limits: Unless specifically designed to do so as part of the training, LLMs may not clearly state that they lack up-to-date knowledge. They often prioritize sounding fluent and helpful over signaling uncertainty, which can mislead users into trusting outdated content.

Because of these behaviors, LLMs alone are unreliable for real-time or evolving knowledge. This is one of the main motivations for Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG), where the model can pull in fresh, external information to overcome its static knowledge limitations. Instead of relying only on what a language model has memorized during training, RAG allows the model to retrieve relevant information from an external knowledge base or document collection and use it to generate responses. This means that, when faced with a query, the system can pull in up-to-date or domain-specific knowledge and integrate it into its generated answer. RAG therefore helps reduce hallucinations by grounding the model's responses in retrieved evidence, giving it a factual basis to draw from rather than relying solely on what it "remembers". This grounding not only improves accuracy but also increases user trust, as responses can often be linked back to source documents.

Another important reason for using RAG is efficiency. Training a large model to know everything is costly, both in terms of computation and data collection. RAG provides a more scalable solution: the model can remain relatively general while relying on retrieval for specialized or fast-changing knowledge. For example, instead of retraining a model every time new medical research is published, a RAG system can simply retrieve the latest articles from a medical database. This modularity makes RAG both practical and flexible for real-world deployments.

How does it Work?¶

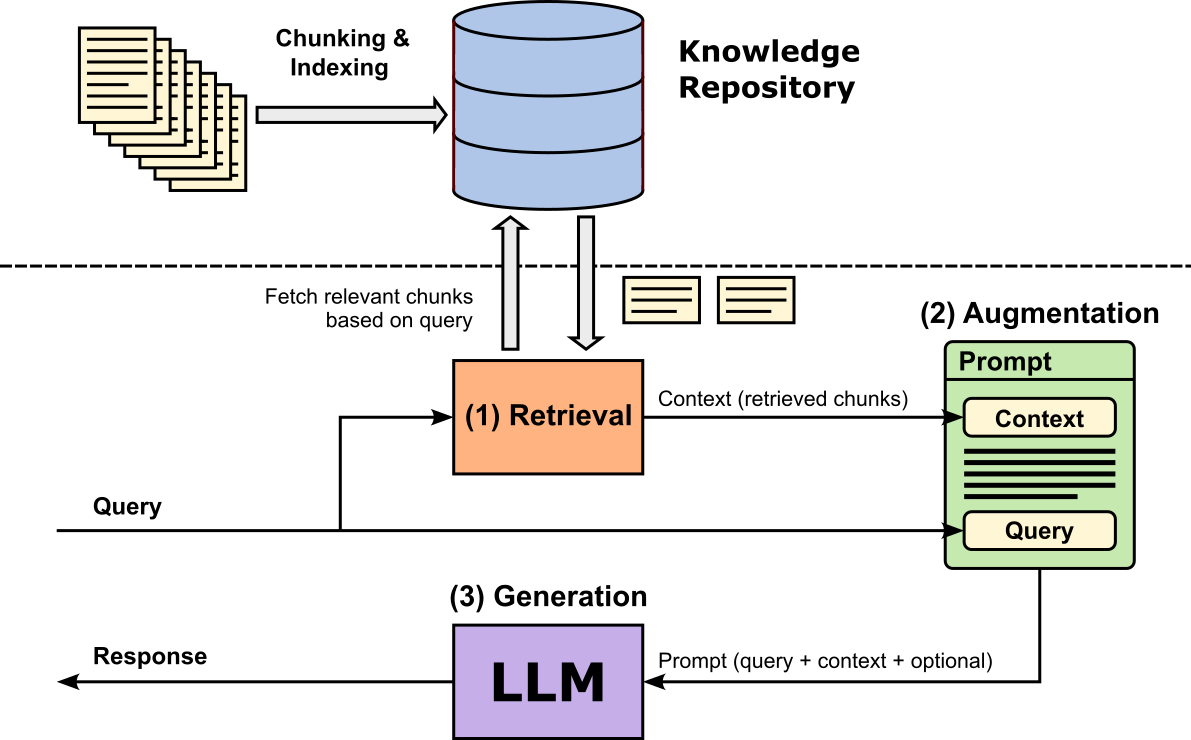

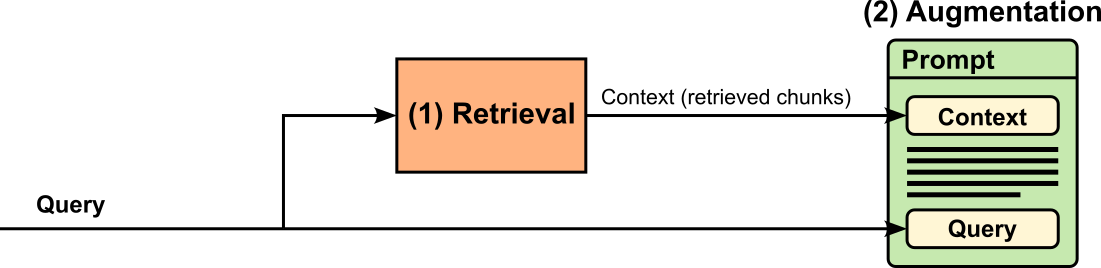

The figure below shows the architecture of a basic RAG pipeline. In a nutshell, RAG uses a curated knowledge repository or database to augment user queries before prompting the LLM. To create the repository, the documents in the dataset (e.g., internal company data or sensitive healthcare data) are first split into smaller chunks, and then stored and indexed in the repository. Given a user query, the retriever then fetches the most relevant chunks with respect to the user query. Augmentation then refers to the step of combining the query, the retrieved chunks, as well as any other optional instructions into the final prompt. This prompt is then given to the LLM to generate the response which is then returned to the user.

A key assumption in RAG is therefore that the answer to a user’s query is already contained within the retrieved chunks. In other words, the retrieval step is expected to provide all the information needed for the LLM to generate an accurate and complete response. The model's primary role is thus not to invent or infer new knowledge, but to extract, synthesize, and rephrase the relevant content from these chunks into a coherent answer. This assumption is critical but also limiting: if the retrieval step fails to surface the necessary information, or retrieves incomplete or irrelevant chunks, the LLM’s output will likely be inaccurate or uninformative, regardless of its reasoning ability. Therefore, the performance of a RAG system depends heavily on the quality of retrieval, including how documents are chunked, indexed, and ranked for relevance.

Knowledge Repository Creation¶

Building a high-quality knowledge repository is one of the most critical steps for an effective RAG pipeline. Since the retriever's job is to identify the most relevant information to support the generator's response, the usefulness of the entire pipeline depends directly on what is stored and how it is structured. A well-organized and semantically meaningful repository ensures that the system retrieves precise, trustworthy, and contextually appropriate information, thus reducing hallucinations and improving factual accuracy in generated outputs. While the quality of the data — correct, consistent, up to date, etc. — is naturally important, it depends on the actual application use case. In the following, we therefore focus on the two core steps required by all RAG pipelines: chunking and indexing.

Chunking¶

In RAG, we typically work with chunks instead of entire documents because large documents are often too long to fit into the LLM's input context window. Modern LLMs have token limits, and if we tried to feed an entire document, much of the input would be truncated or ignored. By splitting content into smaller, semantically meaningful chunks, we ensure that relevant information can be retrieved and passed into the model without exceeding its processing limits. This makes retrieval more efficient and precise, since only the most relevant portions of text are selected. Additionally, we can still control the size of the input by deciding how many chunks we use to form the context for the final prompt.

Another reason for chunking is improving retrieval accuracy. When documents are stored as a whole, the retrieval system might select a document that contains some relevant information, but most of it could be irrelevant. This dilutes the context provided to the LLM and can lead to off-topic or less accurate answers. With chunking, retrieval is done at a finer granularity, so the model gets exactly the passages that matter. This reduces noise, increases precision, and allows the LLM to ground its responses more directly in the most relevant evidence. Of course, this assumes that the chunking, indexing, and then later the retrieval is implemented appropriately.

While the general idea of splitting a large document into smaller chunks seems straightforward, there are both conceptual as well as practical challenges involved when it comes to finding "good" chunks. We said before that we are looking for semantically meaningful chunks. While there is no single best definition, a semantically meaningful chunk preserves complete, coherent units of meaning from the source text, such that each chunk can stand on its own for retrieval and interpretation without relying heavily on missing surrounding context. For more detail, let's break this down further:

Preserve coherence: A chunk should capture a full thought or concept (e.g., a paragraph explaining one idea, a subsection describing a method, or a set of sentences that jointly define a term). Cutting in the middle of a definition, table, or argument would reduce usefulness because the chunk loses context.

Retrievable utility: Each chunk should be "retrieval-ready", that is, if it surfaces as a top result, it should provide enough information for the model to either directly answer a query or serve as a reliable grounding source.

Balance between size and meaning: Too small, and chunks lose meaning; too large, and they may dilute retrieval precision and exceed token constraints. The "sweet spot" is often paragraph-level or section-level segments, sometimes with sliding windows for continuity.

Addressing these goals for chunking also depends on the type of document. In case of general text (e.g., articles, books, reports) paragraph boundaries as well as headings/subheadings are natural cut points, since authors typically organize one idea per paragraph. Academic or technical papers often have clear logical units (e.g., abstract, problem definition, method description, experimental setup, evaluation) which should arguably be preserved during chunking. Papers also often include equations, tables, and figures. Not only should chunking avoid splitting formulas or tables, a good chunk should contain the formula/table/image including some of the surrounding text. When chunking dialogue or conversation, each chunk should split at speaker turns, and also group say, 3-5 consecutive turns to preserve some coherence of the conversation. Particularly question-answer pairs should be in the same chunk. As a last example, chunking source code should preserve complete functions, classes, or config blocks, together with an documentation (e.g., comments, docstrings).

Given the variety of document types and the non-obvious idea of a semantically meaningful chunk, there is also no single chunking strategy. Apart from the type of the input documents, these strategies also offer trade-offs between simplicity, accuracy, efficiency, and adaptability. Typically, the better a strategy can preserve the coherence of chunks the more complex its implementation, and vice versa. Let's have a look at some of the most popular strategies together with their pros and cons:

Fixed-size (naïve) chunking is the simplest way to split documents. The text is divided into uniform windows based on a fixed number of tokens or characters (e.g., every 512 tokens). The method is straightforward to implement and works reliably across large datasets without requiring domain-specific logic or preprocessing. However, its main drawback is that it ignores the semantic structure of the text. A chunk may split in the middle of a sentence, paragraph, definition, or code block, resulting in fragments that lack meaning or context. This can make retrieval less precise, since the retrieved chunk might not provide a coherent answer on its own. While fixed-size chunking is useful for speed and scalability, it often sacrifices semantic fidelity and is less effective for domains that require nuanced understanding (e.g., legal text, scientific articles).

Sliding chunking (or overlapping chunking) is a strategy where text is split into fixed-size chunks, but with intentional overlap between consecutive chunks. For example, each chunk containing 512 tokens might overlap the previous one by 50-100 tokens. This overlap helps preserve continuity at the boundaries and reduces the risk of losing meaning when sentences or concepts span across chunk boundaries. The downside, however, is increased storage and indexing cost, as overlapping content leads to redundancy. Retrieval might also return multiple very similar chunks, which the system must handle carefully. Despite these trade-offs, sliding chunking is popular in practice for domains like technical documentation, code, and conversational text where context continuity is crucial.

Structure-based chunking splits text according to natural boundaries in the document, such as paragraphs, headings, sections, bullet lists, or code blocks. Instead of cutting at arbitrary lengths, it respects the author's intended organization, ensuring that each chunk represents a semantically meaningful unit. It avoids fragments that cut off mid-sentence or mid-definition, which improves answer quality. The drawback is that chunks can vary widely in size, some may be too short to provide enough context, while others may exceed token limits if a section is long. This makes it less predictable for indexing and may require further hybrid strategies (e.g., recursive splitting) to handle very large sections.

Recursive chunking is a hybrid strategy that combines structure-awareness with size control. The idea is to first split a document at larger, natural boundaries (e.g., sections, paragraphs, headings). If a resulting piece is still too large with respect to some maximum size, it is recursively broken down into smaller units, such as sentences or sub-sentences, until it fits within the desired chunk size. This preserves semantic coherence as much as possible, while guaranteeing that all chunks remain within practical token limits. The main benefit of recursive chunking is that it balances semantic fidelity with technical constraints. It avoids cutting text arbitrarily, while still ensuring compatibility with retrieval and generation systems. However, it is more complex to implement than simple fixed-size chunking, and in some cases, the final smaller splits may still feel fragmented if the original content was unusually long or dense. Despite these challenges, recursive chunking is one of the most widely used strategies in modern RAG frameworks because it adapts well across domains.

Semantic chunking is a more advanced chunking strategy that focuses on splitting text based on meaning or topic shifts rather than arbitrary fixed sizes or structural elements like paragraphs. It works by first breaking text into small units (like sentences) and then using an embedding model to measure the semantic similarity between adjacent units; a significant drop in similarity indicates a natural "break point", ensuring that each resulting chunk contains a coherent, complete idea. The main advantage of semantic chunking is that it produces highly meaningful, contextually self-contained chunks that align with how humans naturally organize and query information. This often improves retrieval precision and answer quality. The drawback is that it is computationally heavier to implement, requiring embedding models or NLP tools for pre-processing, and the resulting chunks may vary widely in length, sometimes exceeding token budgets. As a result, semantic chunking works best in high-value domains (e.g., legal, financial, or scientific documents) where retrieval accuracy outweighs processing cost.

Modality-specific chunking addresses documents containing mixed content, such as text, tables, images, and code. Instead of applying a single rule to the entire document, this method handles each content type (modality) separately, applying tailored chunking rules. For example, it might use semantic chunking for paragraphs of prose, treat an entire table as a single, large chunk (perhaps converted to a structured text format), and index code blocks based on logical units like functions or classes. This ensures that the contextually important elements of each different content type are preserved during the splitting process. The main pro is significantly improved retrieval accuracy for complex, multi-format documents like scientific papers or technical manuals, because it ensures that tables and figures are indexed coherently and retrieved alongside their corresponding explanatory text. However, the primary con is the high engineering complexity; it requires dedicated parsers and logic for every modality, leading to increased development time and maintenance overhead compared to simpler, uniform chunking methods.

Agentic chunking is a sophisticated strategy that uses an LLM or a specialized agent to intelligently determine how to split a document. Unlike methods with fixed rules, agentic chunking analyzes the content to find natural, logical breakpoints, similar to how a human would read and segment a document. This often involves an initial split into small units like sentences or "propositions" (self-contained statements), followed by the agent dynamically deciding whether to group these units into a larger, coherent chunk based on semantic meaning, document structure, or the expected use case. The primary pro is its ability to produce highly relevant, contextually rich chunks that lead to more accurate and complete answers from the RAG system. However, the main con is that it is computationally expensive and complex to implement. The process requires multiple calls to an LLM during the preprocessing phase, which increases both cost and latency compared to simpler, rule-based chunking methods.

Apart from these main chunking strategies, practical implementations often combine different strategies for better results. The choice of chunking strategy depends on multiple factors, including the type and modality of the documents, the specific use case of the RAG system, and resource constraints such as processing power, storage, and indexing requirements. For example, technical or legal documents may benefit from structure- or semantic-aware chunking, while large-scale corpora may rely on fixed-size or sliding windows for efficiency. Ultimately, selecting the right strategy requires balancing retrieval quality, computational cost, and the nature of the content to create chunks that are both practical and semantically useful.

Indexing¶

So far, we have taken our input documents and split them into chunks of appropriate size(s) to fit the context size of the LLM we use or other constraints. This includes that we can store all chunks, typically with other metadata (mainly the information about the original source document), in some database or other knowledge repository. Now we have to make the chunks retrievable or searchable to find the most relevant chunk(s) for a given input query. This is where indexing comes into play.

An index n a database or knowledge repository storing text chunks is a structured data component that maps the features of chunks (e.g., concepts, keywords, semantic) to their location in the repository, enabling efficient search and retrieval. The index then acts as a bridge between input queries and relevant chunks based on the similarity between the same features of an input query and the chunks. The more similar the features of a query and a chunk are, the more relevant is the chunk for that query. There are two main types of indexes that are commonly used for RAG: full-text search and vector search.

Full-Text Search¶

Full-text search is a technique for searching a single chunk or a collection of chunks by examining every word of the text to find the most relevant results for a query. For example, given a query such as "What is the height of Mount Everest?", chunks are considered most relevant if they contain the terms "height", "Mount", "Everest" — or even the phrase "Mount Everest". The most common index to support full-text search is the inverted index. It works by mapping each unique term (typically ngrams or words) in a collection of documents (or chunk) to a list of all the documents where that token appears. By precomputing these word-to-document mappings, the inverted index allows users to quickly locate and rank documents that match a query, without scanning every text file.

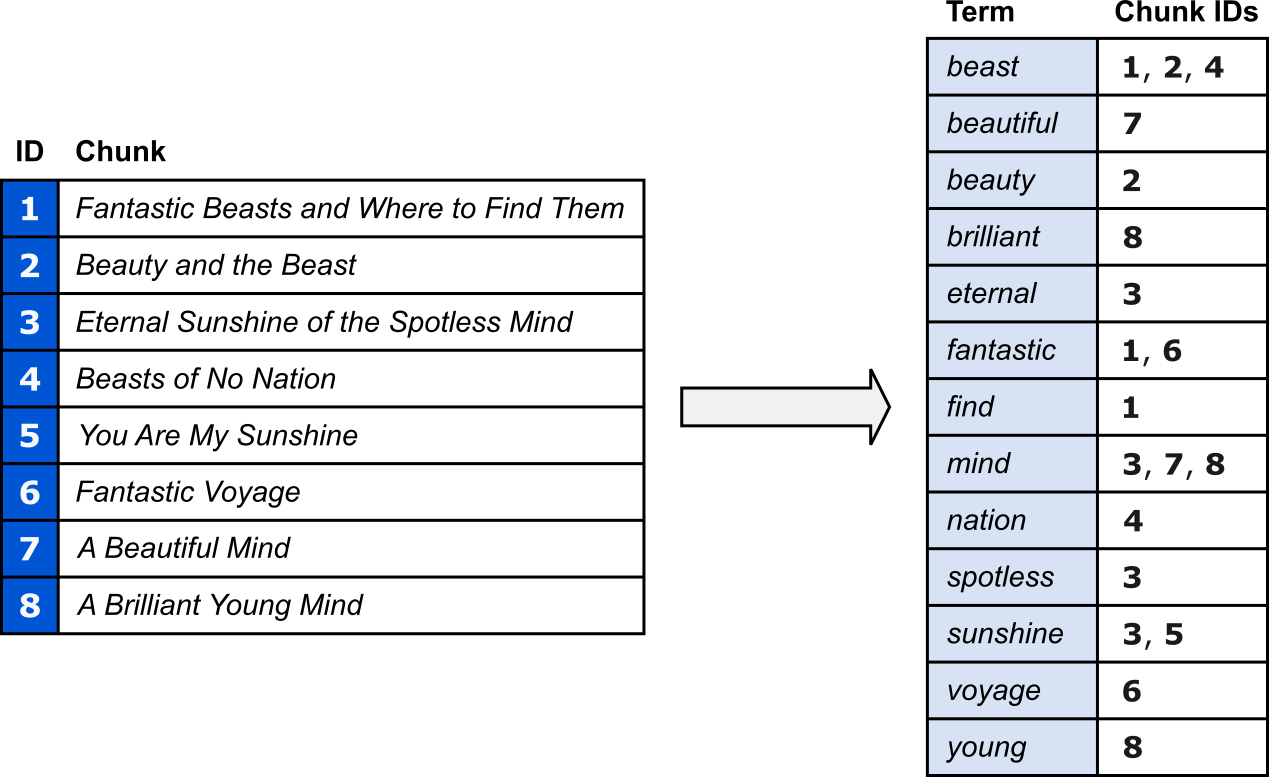

The figure below shows a basic example of an inverted index. In this example, for simplicity, we assume all chunks are movie titles. Before indexing each term (here: words), we also perform several common preprocessing steps:

- Stopword and punctuation removal: Both stopwords (e.g., prepositions, pronouns, conjunctions) and punctuation marks typically do not have any semantics on their own to meaningfully describe the content of a chunk; they are therefore often removed before the indexing.

- Normalization: All words are changed to lowercase and lemmatized (i.e., converted into their base form). This allows us to ignore syntax variations that typically do not change the meaning of a word (e.g., plural vs. singular nouns, or the tense of verbs).

After the preprocessing, we can now build the inverted index by mapping each unique term/word to the IDs of the chunks that contain these terms. For example, "beast" appears in Chunk 1, 2, and 4. Notice how Chunks 1 and 4 contain the plural form of "beast", but which are ignored due to lemmatizing each word.

When receiving a user query, we first need to perform the same preprocessing steps to extract all terms from the query. We can then use the inverted index to quickly look up which chunks contain one or more of the query terms, and potentially rank the match chunks with respect to the overlap. Note that the inverted index shown above represents the most basic implementation. Beyond chunk IDs, inverted indexes typically store detailed information to improve ranking and query accuracy. This includes term frequency (TF) to measure how often a word appears in a document, and term positions to enable phrase and proximity searches, and others. At a global level, the index maintains term statistics such as document frequency (DF) and inverse document frequency (IDF), which help identify distinctive versus common terms. Together, these elements make inverted indexes not just efficient for retrieval, but also powerful for relevance scoring and advanced search features.

Pros¶

Using full-text search based on inverted indexes provides a highly efficient and interpretable retrieval mechanism for RAG systems. An inverted index allows RAG pipelines to perform keyword-based searches extremely quickly, even across millions of documents. Since RAG systems often need to retrieve supporting information in real time before passing it to a language model, such speed and efficiency are crucial for maintaining low-latency responses. Inverted indexes are also scalable and storage-efficient. Instead of storing full documents, the index only contains references and term frequencies, which keeps the overall memory footprint low.

Full-text search also provides high precision when queries contain specific terms, entities, or keywords that are directly mentioned in the source texts. For domains where terminology overlap between user queries and documents is high (e.g., legal, scientific, or technical information) this approach ensures that retrieved chunks are highly relevant. A closely related strength lies in transparency and control. Inverted index–based retrieval is deterministic and interpretable. This means that you can easily see which words triggered a match and how documents were ranked. This is particularly valuable for debugging or fine-tuning RAG pipelines, as it allows direct inspection of retrieval quality and user query behavior.

Lastly, full-text search is a well known and well understood task. Mature search engines like Elasticsearcho or Lucene are optimized for these operations and can easily scale to enterprise-level or web-scale datasets. This makes inverted indexes especially practical for large knowledge bases that need to be updated or queried frequently. Their inverted indexes often include ranking mechanisms such as TF-IDF or BM25, which prioritize documents where query terms appear more meaningfully. Additionally, these systems support flexible query features such as phrase matching, wildcards, fuzzy matching, and boolean logic, which can significantly enhance retrieval accuracy in specific applications.

Cons¶

The main drawback full-text search is that inverted indexes rely purely on lexical matching, meaning they retrieve documents that contain the same words as the query. This approach fails when users phrase questions differently or use synonyms, paraphrases, or related terms not explicitly present in the chunks. This includes inverted indexes struggle with semantic understanding. They treat text as a collection of words without capturing deeper relationships, meanings, or context. For example, a query like "How to prevent heart disease?" might not retrieve documents that discuss "reducing cardiovascular risk" unless those exact terms overlap. In RAG systems, where understanding nuanced meaning is often crucial, this lack of semantic comprehension can lead to less informative or incomplete responses from the language model.

Full-text search also faces challenges with multilingual, unstructured, or domain-specific data. Since inverted indexes depend on exact word forms, they require extensive preprocessing (e.g., stemming, lemmatization, and stopword removal) to work effectively. However, these steps can be language-specific and difficult to generalize across diverse corpora. Similarly, in specialized fields like medicine or law, where terminology and synonyms are abundant, keyword-based retrieval often underperforms unless carefully tuned. Lastly, this also includes that inverted indexes do not directly support multiple modalities and are generally limited to text chunks.

Vector Search¶

One of the limitations of traditional full-text search using inverted indexes is that it essentially relies on exact word matches. In many real-world queries, however, users may express their intent using different wording, synonyms, or paraphrases that may not appear literally in the source documents. Vector search addresses this problem by representing both queries and documents as dense numerical embeddings that capture their semantic meaning rather than their surface form. This allows the retrieval process to find conceptually similar text even when the exact words differ.

The core idea of vector search is to use a pretrained embedding model — often derived from Transformers architectures such as BERT or Sentence Transformers — to map text (sentences, paragraphs, or chunks) into a shared high-dimensional space. These embedding models are trained so that semantically related pieces of text lie close to each other in the embedding space, while unrelated ones are far apart. When a user query arrives, it is converted into an embedding vector and compared with stored document embeddings using similarity metrics such as cosine similarity or dot product. The top-ranked vectors represent the most semantically relevant documents or chunks for the RAG system to feed into the language model.

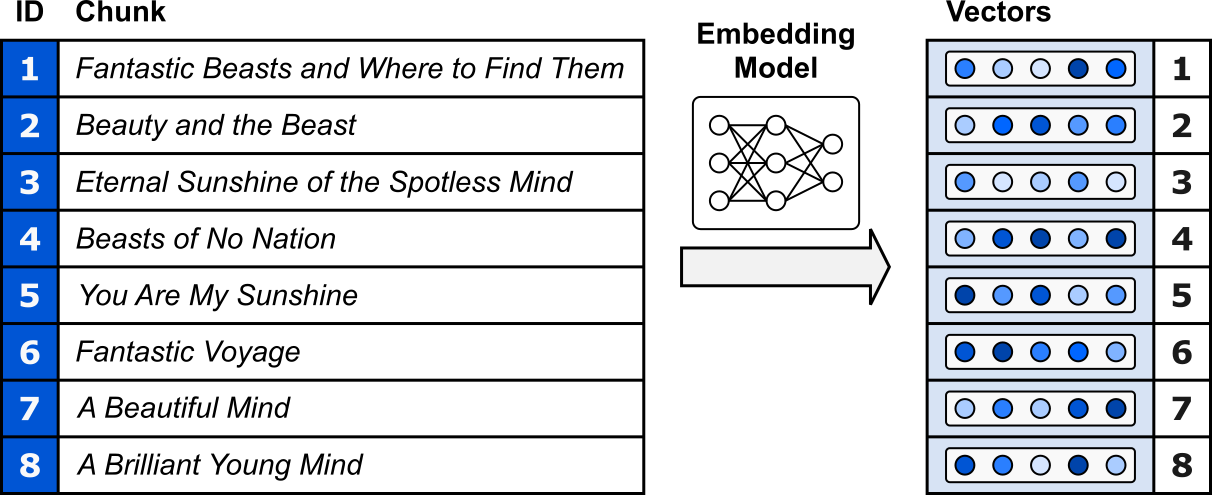

The figure below shows an example using our 8 example chunks. Each chunk is fed into a pretrained embedding model which maps each chunk to a vector representation. To ease presentation, we only map chunks to 5-dimensional embedding vectors. In practice, these embedding vectors typically have a size of several hundreds or several thousand entries.

The same pretrained embedding model is then also used to transform each user query to its corresponding embedding vector. We can then retrieve the most relevant chunks(s) based on the similarity between the query vector and chunk vectors. The more similar the vectors, the more relevant is a respective chunk to the user query. Finding the most similar vectors (nearest neighbors) among potentially millions or billions of stored embeddings is computationally expensive, both in time and memory. Thus, a lot of more advanced strategies are required to find the most similar vectors efficiently. However, a more detailed discussion of such strategies is beyond the scope of this notebook.

Pros¶

Compared to full-text search, vector search has ability to capture semantic similarity rather than relying on exact keyword matches. By representing queries and documents as dense embeddings in a shared vector space, vector search can retrieve relevant information even when the wording differs. For example, a query like "ways to lower blood pressure" can retrieve documents about "reducing hypertension", something traditional keyword search would likely miss. This makes vector search also more robust to natural language variation. Because embeddings encode contextual meaning, vector search performs well even with informal phrasing, spelling variations, or multilingual input. This allows RAG systems to support a wider range of user queries without requiring exact alignment between query and document vocabulary.

Vector search also enhances retrieval quality and response coherence. Since retrieved chunks are semantically aligned with the query's intent, the language model receives more meaningful and contextually relevant context. This often leads to responses that are more accurate, grounded, and natural. Moreover, embedding-based retrieval can capture relationships across sentences or topics, helping RAG systems retrieve documents that match the overall idea rather than isolated words. This also includes can handle multiple modalities beyond text. Since embeddings can represent not only language but also images, audio, and video, RAG systems can retrieve and reason across different types of data in a unified vector space. This enables multimodal applications such as answering questions about images or combining textual and visual context—using the same underlying retrieval framework.

While relatively new compared to full-text search, the popularity of vector search spurred the development of many vector databases (like FAISS, Milvus, or Pinecone) that are optimized for scalable similarity search, enabling efficient retrieval even from millions of embedded chunks. This scalability makes it practical for large knowledge repositories. Finally, vector search is well-suited for continuous improvement and adaptation. Since embeddings can be fine-tuned for specific domains or tasks, the retrieval quality can improve over time without re-indexing text manually. This adaptability, combined with semantic robustness and scalability, makes vector search a cornerstone of modern RAG systems—particularly in scenarios where understanding meaning, not just matching words, is essential.

Cons¶

One of the main challenges of vector search is its computational cost. Assuming you want or need to train your own embedding model, generating dense embeddings for large document collections requires substantial processing power and storage, especially when using high-dimensional vectors. Searching through millions of embeddings also demands specialized vector databases and approximate nearest neighbor (ANN) algorithms to maintain reasonable latency. This makes vector search more resource-intensive compared to traditional inverted indexes, both during indexing and retrieval. The alternative of training your own embedding model is to use a pretrained model. However, the vector search then depends heavily on the quality and domain relevance of the embedding model. Pretrained embeddings might not fully capture the nuances of specialized or technical language, leading to semantically imprecise retrievals.

Another major limitation is the lack of transparency and interpretability. Unlike keyword-based search, where it is clear which terms matched, vector search relies on abstract embeddings that are difficult to interpret. When a retrieved document seems irrelevant, it can be challenging to understand why it was selected or how to adjust the retrieval behavior. This opacity complicates debugging, evaluation, and trust in RAG systems, especially in domains that require explainability, such as healthcare or law.

From a systems perspective, scalability and maintenance pose additional challenges. Storing and updating large vector indexes can become expensive and complex, particularly when the knowledge base changes frequently. Vector indexes often require batch processing and re-embedding steps to remain consistent which can limit their flexibility in dynamic environments where data updates occur continuously. Finally, while vector search enables semantic retrieval, it sometimes suffers from semantic drift and may retrieve conceptually related but factually irrelevant content. Because embeddings prioritize meaning over exact wording, results can be topically similar yet miss critical factual details. For RAG systems that aim for factual grounding, this can lead to the generation of subtly incorrect or off-topic responses.

Indexing Strategies — Summary¶

In Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG), the two main retrieval strategies are full-text search and vector search. Full-text search relies on inverted indexes to quickly find documents containing exact query terms, offering fast, interpretable, and resource-efficient retrieval. However, it struggles with synonyms, paraphrases, and semantic understanding. Vector search, on the other hand, uses dense embeddings to capture the meaning of queries and documents, enabling semantic retrieval, handling natural language variation, and even supporting multiple modalities. Its drawbacks include higher computational cost, lower interpretability, and reliance on embedding quality.

The choice between these strategies depends on the application's requirements, such as latency constraints, domain specificity, and the importance of semantic versus exact matches. In practice, many RAG implementations adopt hybrid approaches, combining full-text and vector search to leverage the speed and precision of keyword matching with the semantic flexibility of embeddings. This allows systems to maximize relevance, coverage, and efficiency across a wide range of queries and document types.

RAG-based Prompting¶

With the knowledge repository with all chunks stored and indexed, we can now use it to enhance the generation of responses to user queries by augmenting the queries with the most relvant chunk or set of chunks. We already outlined the basic workflow in the overview section showing the overall architecture of a basic RAG pipeline. Let's look at all the involved steps a bit more closely.

Retrieval¶

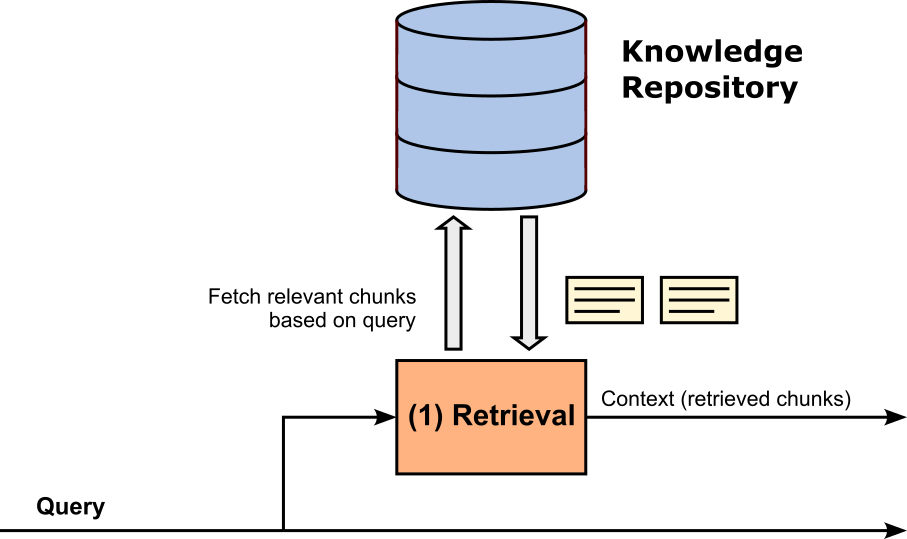

The retrieval step is the actual step that involves the knowledge repository; see the figure below. Each query is passed to the retriever which in turn uses this query to fetch the most relevant chunks, either using full-text search, vector search, or a hybrid approach, depending on the exact implementation of the knowledge base.

At the bare minimum, the knowledge repository returns the most relevant chunk — or no chunk at all if the query does not (sufficiently) match any chunk. However, In modern RAG systems, the retriever is often extended beyond simple similarity search to improve the relevance and usefulness of the retrieved chunks. A common extension is multi-stage retrieval, where the system first retrieves a broader set of top-(k) candidate chunks and then applies a re-ranking step to refine the results. Re-ranking typically uses a pretrained model to score how well each chunk matches the query in context, providing more accurate and contextually aware results than vector similarity alone.

Another popular enhancement is query expansion or reformulation, where the original user query is rewritten or enriched — often using a language model — to capture different phrasings or related concepts. This helps the retriever overcome embedding limitations and improves recall for complex or ambiguous questions. Some systems also use iterative retrieval, where the generator's intermediate reasoning or partial answer is fed back into the retriever to refine subsequent searches, creating a feedback loop between retrieval and generation. Many other minor and major refinements to this basic retrieval step are possible and are often customized to the application use case.

All retrieved chunks (that also pass any potentially re-ranking or filtering steps) are considered the context, which is then used for the augmentation step.

Augmentation¶

The augmentation step assembles the final prompt that gets submitted to the LLM. The prompt naturally includes the original query and the context, but may also include other instructions. A common example for such an instruction may tell the LLM to use only the provided context to generate the reponse (instead using any other information captured as part of the training). Another common instraction may specify the format (e.g., paragraphs, bullet points, Json/XML, etc.) or the style (e.g., formal vs. informal) of the response. The figure below shows the augmentation step. Any content between the context and the query illustrates any additional instructions.

Note that in the figure above, the order of the prompt — context, optional instructions, query — is just an example. In practice, more structured templates may be used to combine all components into the final prompt. The snippet below shows a very simple example of such a template:

You are a helpful assistant. Use the context below to answer the question truthfully.

### Context:

{chunk_1}

{chunk_2}

{chunk_3}

### Question:

{user_query}

### Answer:

Using this template, {chunk_1}, {chunk_2}, {chunk_1}, and {user_query} get replaced the retrieved chunk (here 3) and the original query. The format of the template may depend on how the LLM was originally trained or fine-tuned but can otherwise be structured very differently. Overall, the only (hard) requirement is that the size of the prompt does not exceed the maximum context size of the LLM.

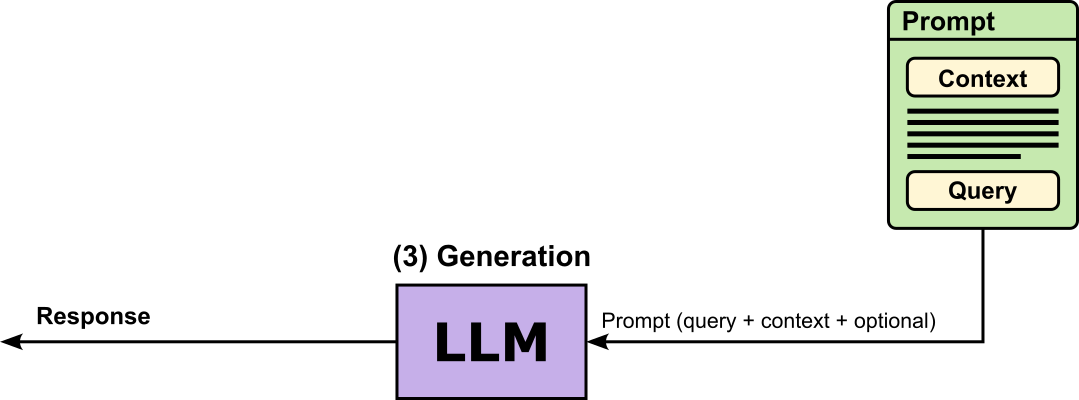

Generation¶

Now that we have the final prompt, all that is remaining is to pass this prompt to the LLM to generate the response; see figure below. In general, the quality of the response depends on both the accuracy of the model and the prompt. However, we typically can only affect the prompt. And since the quality of the prompt mainly depends on the quality of the retrieved content, it becomes obvious how important the creation of the knowledge base as well as the retrieval step of the RAG pipeline are.

Using this basic setup, the response generated by the LLM is returned to the user. However, not all RAG systems return the (initial) response directly to the user. In many advanced pipelines, the model's output serves as an intermediate step in a larger reasoning or validation process. For instance, verification-oriented RAG systems use a secondary model or process to check the factual accuracy and consistency of the initial answer against the retrieved evidence before presenting it to the user. This helps reduce hallucinations and improves trustworthiness in sensitive domains like law, medicine, or enterprise knowledge systems.

Other RAG architectures adopt an agentic or multi-step reasoning approach, where the first response triggers further retrievals, computations, or follow-up questions. The final answer is only produced after several iterations of reasoning and evidence gathering. This enables more complex, multi-hop reasoning and deeper contextual understanding. Some RAG pipelines use the LLM's outputs for non-user-facing purposes**, such as content moderation, compliance checks, or knowledge base enrichment. In these setups, the generated responses are filtered, validated, or transformed before becoming visible — or are used to improve the repository itself. In all such cases, the goal is to move beyond immediate generation toward more accurate, interpretable, and reliable knowledge workflows. But such advanced strategies are beyond our scope here.

Discussion¶

RAG can be powerful to integrate new knowledge into a pretrained LLM. However, this does not make RAG perfect, and does come with its own set of limitations and challenges. Some of those can be addressed through more advanced RAG pipelines. Also, RAG is not the only strategy to extend the knowledge of a pretrained model. A common alternative is fine-tuning. Let's briefly discuss all the considerations.

Limitations & Challenges¶

Despite its flexibility and power, RAG also comes with several core limitations that affect its performance, scalability, and reliability. These challenges mainly arise from its dependence on retrieval quality, context management, and integration between retrieval and generation:

Importance of retrieval step: If the retriever fails to find relevant or accurate documents, the generation step will produce poor or incorrect answers, even if the LLM itself is strong. This issue often stems from limitations in indexing, chunking, or query formulation (for example, when relevant information is phrased differently than the user query or split across multiple chunks). In such cases, RAG may retrieve irrelevant or incomplete context, leading to hallucinations or misleading answers.

Context and scalability constraints: The model can only process a limited number of retrieved passages due to the LLM's context window size. This means potentially relevant information may be excluded or truncated, especially in large knowledge bases. Managing which chunks to include, in what order, and how to combine them effectively is a key design challenge. This challenge becomes harder as document collections grow.

Shallow knowledge integration: Unlike fine-tuning, where knowledge is embedded directly into model weights, RAG merely "borrows" information at inference time. This can lead to inconsistencies across responses, as the model does not permanently internalize the new knowledge. Additionally, retrieved text may conflict or overlap, requiring the model to reason over noisy or redundant information — something LLMs are not always robust at handling.

Some of these limitations spurred the development of more advanced RAG solutions.

Advanced RAG Pipelines¶

In this notebook, we introduced RAG by focusing on the most basic setup of a single sequence of retrieve, augment, and generate. However, the strengths and popularity of RAG have resulted in the exploration and development of more advanced RAG pipelines. The list below outlines some of the more common approaches.

Multi-Stage or hierarchical retrieval: Instead of a single retrieval step, multiple successive steps allow to progressively refine the set of candidate documents or chunks. The first stage typically performs a broad, recall-oriented search (e.g., using a fast keyword-based full-text search) to collect a large set of potentially relevant results. The next stage then applies a more precise, semantic filtering step, often using a vector search, to narrow down this initial pool to the most relevant passages. This is especially useful when working with large or heterogeneous knowledge repositories, where a single retrieval method might either miss key documents or return too many irrelevant ones.

Query expansion and reformulation: Instead of relying on the raw query, the system generates alternative or extended versions that capture synonyms, related concepts, or sub-questions. For example, a query like "Who started OpenAI?" could be expanded to include terms like "OpenAI founders" "OpenAI creation" or "founding members of OpenAI". This can be done using linguistic methods (e.g., synonym dictionaries), statistical methods (e.g., co-occurrence analysis), or LLM-based reformulation (where the model itself generates better retrieval queries). The main goal is to increase recall, ensuring that relevant information is not missed due to wording differences between the query and the stored documents. Reformulated queries can also make retrieval more context-aware, especially when dealing with ambiguous, under-specified, or multi-faceted questions.

Iterative or feedback-driven RAG: After the model retrieves first information and generates a partial answer, it evaluates its own confidence or identifies missing pieces of information, then issues new or refined queries to retrieve additional evidence. This iterative loop continues until the model has gathered enough context to form a complete and accurate answer. This setup enables multi-hop reasoning, where the model connects facts spread across different documents or knowledge sources — something basic RAG cannot easily achieve. It also improves factuality and coverage since the model can refine its understanding as it goes. Iterative RAG is particularly useful for complex or compositional questions that require combining multiple facts, reasoning through dependencies, or verifying uncertain information before producing a final response.

Modular or Agentic RAG: This approach extends the basic RAG pipeline by breaking it into multiple specialized components or "agents", each responsible for a specific subtask such as retrieval, summarization, reasoning, verification, or synthesis. Instead of a single end-to-end model handling everything, these modules interact in a coordinated workflow, often guided by a controller or orchestrator model. For example, one agent may retrieve documents, another may extract key facts, a third may reason over them, and a final agent may generate a coherent, evidence-grounded answer. This modular structure makes RAG systems more flexible, interpretable, and robust, especially for complex or domain-specific applications like legal, biomedical, or technical QA. Each agent can be optimized or fine-tuned separately, and the system can dynamically decide which modules to activate based on the task.

Of course, the main drawbacks of advanced RAG pipelines lie in their complexity, cost, and manageability. Multi-stage retrieval, query reformulation, or agentic reasoning require multiple model calls, retrievers, and coordination steps, which significantly increase computational overhead and latency compared to a simple one-shot RAG. These pipelines also introduce more hyperparameters (e.g., thresholds, query reformulation depth, number of retrieval rounds) that must be tuned carefully to maintain performance and avoid unnecessary retrieval or reasoning loops.

Additionally, advanced RAG systems are harder to design, debug, and evaluate because of their modular and dynamic nature. Errors can propagate across components — for instance, a poor query reformulation can mislead all subsequent retrieval steps. Maintaining consistency and factual reliability across multiple reasoning or verification stages can also be challenging. As a result, while these advanced architectures offer higher accuracy and reasoning power, they come with trade-offs in engineering complexity, interpretability, and scalability.

RAG vs Fine-Tuning¶

RAG is not the only approach to tackle the central limitation of large language models (LLMs): their static and incomplete knowledge. An alternative method is fine-tuning, which works by adapting the model's parameters through additional training on curated datasets that reflect the desired knowledge or behavior. This allows the model to internalize new facts, terminology, and reasoning patterns, effectively updating its "understanding" of a domain. As a result, fine-tuned models perform better on tasks within that domain and make fewer errors due to outdated or irrelevant pretraining data.

However, particularly when it comes to instilling new knowledge, RAG offers several clear advantages over fine-tuning. The main benefits stem from RAG's flexibility, efficiency, and interpretability compared to the static and resource-intensive nature of fine-tuning; more specifically

Flexibility and easy updates: Instead of retraining the model every time new information becomes available, RAG simply retrieves relevant knowledge from an external repository at inference time. This means that the model can instantly access the latest data — for example, recent research papers or company policies — without any modification to its parameters. In contrast, fine-tuning requires collecting and cleaning new datasets, retraining the model, and validating performance, which is costly and time-consuming.

Efficiency and cost-effectiveness: Fine-tuning large models demands substantial computational resources and expertise, often making it impractical for frequent updates or domain-specific deployments. RAG avoids this overhead because it keeps the model frozen and only manipulates its input context. This also makes it easier to maintain multiple specialized applications using a single base model with different retrieval databases, rather than maintaining many separately fine-tuned versions.

Transparency and control: Because the retrieved documents are part of the model's visible context, you can inspect what information the model relied on to generate its answer. This traceability supports debugging, trust, and interpretability — features largely absent from fine-tuned models, where knowledge is "baked" into the weights and cannot be easily traced or corrected if wrong.

Particularly when the goal is to incorporate new knowledge, fine-tuning also poses unique challenges. Apart from the higher computational cost and complexity (compared to RAG), key difficulty lies in catastrophic forgetting and knowledge integration. When a model is fine-tuned on new data, it may unintentionally overwrite or distort previously learned knowledge, leading to inconsistencies or reduced performance on general tasks. Moreover, because new facts are absorbed into the model's weights, it becomes difficult to precisely control or verify what the model has "learned". Unlike RAG, fine-tuning provides little transparency about the source or correctness of the information embedded in the model.Fine-tuned knowledge is static and hard to update or correct. Once a model has been fine-tuned, removing outdated or incorrect information requires another round of retraining. This makes it unsuitable for applications that demand rapidly changing or verifiable knowledge. As a result, while fine-tuning can deeply align a model with a specific domain, it remains an inflexible and resource-heavy approach for keeping a model's factual knowledge current.

Summary¶

Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) is a powerful framework that enhances large language models (LLMs) by grounding their responses in external knowledge sources. Unlike traditional LLMs that rely solely on their internal training data, RAG dynamically retrieves relevant information from an external knowledge repository, such as documents, databases, or web pages, before generating a response. This approach allows RAG systems to provide up-to-date, factual, and domain-specific answers even when the LLM's internal knowledge is outdated or limited by its training cutoff. As a result, RAG has become one of the most popular and effective methods for extending an LLM’s capabilities without retraining it.

The success of a RAG system depends critically on the quality of the knowledge repository. A well-curated, comprehensive, and up-to-date collection of documents ensures that relevant and accurate information is available for retrieval. If the repository contains errors, outdated facts, or lacks coverage in key areas, the LLM's generated answers will likely reflect these weaknesses. Hence, maintaining and improving the knowledge base is a central part of any robust RAG pipeline.

Equally important is the retrieval step, which determines which pieces of information (known as "chunks") are selected from the repository and provided to the LLM. The retrieval quality directly affects the usefulness of the generated response. Two main strategies dominate this step: full-text search and vector search. Full-text search relies on keyword-based matching, using structures like inverted indexes to efficiently locate documents containing specific terms. Vector search, on the other hand, uses dense embeddings to capture semantic similarity, allowing it to retrieve relevant passages even when the wording differs significantly from the query. Many practical RAG implementations adopt hybrid retrieval, combining both strategies to leverage the precision of keyword matching and the flexibility of semantic search.

RAG offers significant advantages. It improves factual accuracy, reduces hallucination, and enables rapid knowledge updates without retraining large models. It also allows organizations to integrate private or proprietary data securely into LLM workflows. However, RAG also introduces new challenges: retrieval errors can propagate into the final response, the system requires careful chunking and indexing, and combining retrieved information into a coherent prompt for the LLM can be complex. Additionally, retrieval adds computational overhead compared to purely generative systems. Overall, RAG represents a practical and scalable approach to making LLMs more knowledge-aware and contextually grounded.