Disclaimer: This Jupyter Notebook contains content generated with the assistance of AI. While every effort has been made to review and validate the outputs, users should independently verify critical information before relying on it. The SELENE notebook repository is constantly evolving. We recommend downloading or pulling the latest version of this notebook from Github.

Text Tokenization¶

Tokenization is the process of breaking down text into smaller parts called tokens. These tokens can be words, sentences, or even smaller units like characters, depending on the application. For example, the sentence "I love ice cream" can be split into tokens: "I", "love", "ice", and "cream". By breaking the text into these manageable pieces, computers can better understand and process it. The purpose of tokenization in natural language processing (NLP) is to prepare text for further analysis, such as identifying patterns, translating languages, or generating summaries. Since computers do not understand text the way humans do, tokenization helps by converting unstructured text into a structured format that algorithms can work with. This is a critical first step for tasks like text classification, sentiment analysis, chatbot development, and more.

Note: The task of tokenization and the challenges involved are language-dependent. In the following, to keep it simple, we introduce the ideas behind tokenization and common approaches in the context of the English language. However, the notebooks conclude with some discussion highlighting the differences to other languages.

Setting up the Notebook¶

Make Required Imports¶

This notebook requires the import of different Python packages but also additional Python modules that are part of the repository. If a package is missing, use your preferred package manager (e.g., conda or pip) to install it. If the code cell below runs with any errors, all required packages and modules have successfully been imported.

from src.utils.libimports.tokenizing import *

Motivation: From Strings to Tokens¶

Text data is one of the most common forms of data. On the internet, a significant portion of content exists as text, including web pages, social media posts, emails, product reviews, blogs, and news articles. This prevalence is due to the ease of generating, sharing, and storing text-based information compared to other formats like video or audio. In companies, text data is equally pervasive, taking the form of emails, customer support chats, reports, documentation, surveys, and user-generated content such as feedback or reviews. Many business operations, like marketing, customer service, and decision-making, rely heavily on analyzing and extracting insights from this text data. As a result, text data is a valuable resource for both understanding user behavior and driving strategic decisions. When working with text data, there are two main perspectives: seeing text as a string or seeing text as written language.

Text as String¶

The most basic way to treat a text is as a string. A string is a sequence of characters, where a character is a single unit of text, such as a letter, number, symbol, or whitespace. Strings are a basic data type in most programming language or database systems to store and manipulate text data. For example, the sentence "Alice gave the book to Bob." can be considered as the following list of characters:

A|l|i|c|e| |g|i|v|e| |t|h|e| |b|o|o|k| |t|o| |B|o|b|.|

Strings, as a sequence of characters, have no intrinsic notion of words, phrases, sentences, etc. This greatly limits an direct analysis of the data for any higher-level tasks or applications such as text classification, sentiment analysis, machine translation, question answering, etc. Any meaningful steps when working with basic strings are generally limited to basic pattern matching, e.g., to see if text contains a certain substring or substring pattern. A common method for substring pattern matching are Regular Expressions. For illustration, the code cell below shows an example of using a simple Regular Expression to find email addresses in a text (i.e., a string). The findall() method in Python's re module is used to search a string for all occurrences of a pattern specified by a regular expression and returns them as a list. It is commonly used for extracting multiple occurrences of patterns, such as phone numbers, email addresses, or words, from a string.

text = "After I got too many spam email to my robert@example.org address, I'm now using bobby@example.org for my correspondence."

# Simple(!) RegEx to match email addresses

email_regex = r"[\w.-]+@[\w.-]+\.[\w]{2,}"

# Find all email addresses

email_addresses = re.findall(email_regex, text)

print(email_addresses)

['robert@example.org', 'bobby@example.org']

Side note: The Regular Expression used in the code cell below to match email addresses is very simple. On the one hand, this expression will not match email addresses containing other special characters beyond . and - but are valid characters according to the official email standard. On the other hand the expression will match substrings that are not valid email addresses, e.g., ---@---.aaa. You can edit the example text in the code cell above to see what substring the Regular Expression will match or not.

While substring (pattern) matching is very useful for many applications; in fact, Regular Expressions are commonly used for tokenization — strings do not capture the meaning or context of words or sentences required for most natural language processing tasks.

Text as Written Language¶

Natural language refers to the way humans communicate with each other to express and share our thoughts, feelings, opinions, ideas, etc. It is called "natural" because it develops organically over time, shaped by culture, society, and human interaction, rather than being deliberately designed like programming or formal languages. While Natural language does have many rules, these rules have emerged instead of being defined a-priori. Text or writing is simply a visual representation of natural language, and a writing system is an agreed meaning behind the sets of characters that make up a text (most importantly: letters, digits, punctuation, white space characters: space, tab, new line, etc.)

One of the most fundamental build blocks of natural language are words. A word is a basic unit of language that has meaning and can be spoken, written, or signed. Words are made up of one or more letters and are used to express ideas, describe things, or communicate actions. For example, "cat," "run," and "happy" are all words, each representing something specific: an animal, an action, and a feeling. Words can stand alone or combine with other words to form phrases and sentences, allowing us to convey more complex thoughts. They follow certain rules of grammar depending on the language being used. While words are arguably the most important building blocks, in natural language processing, we generally use the term token to also include punctuation, numbers, white space or any other special characters.

The Task of Tokenization¶

The purpose of tokenization is to convert a text from a sequence of characters (i.e., a string) into a sequence of tokens for further processing. In other words, we want to split a string into meaningful blocks or substrings we call tokens. Which types of substrings are considered tokens depends on the exact tokenization approach. For example, tokens might be individual characters, words, or anything in between (i.e., so-called subwords). A more detailed overview to these fundamental approaches is given below. For basically all natural language processing tasks, tokenization is one of the most common and fundamental steps. It is also often the first step to be performed, which makes it very important to get it right.

The result of tokenization is not only the sequence tokens but also, at least implicitly, the vocabulary. The vocabulary is simply the set of unique tokens across a whole tokenized text corpus. The information about the vocabulary is important since many models used in Natural Language Processing assume a fixed vocabulary size. For example, a text classifier trained on some text corpus only "knows" the tokens the model has seen during training. However, a new unseen document for which the model is expected to predict a class label might contain one or more unknown tokens. Such unknown tokens that were not present in the vocabulary during training are referred to as OOV tokens (short for "Out-of-Vocabulary tokens"). A deeper discussion about the effect of OVV tokens and common strategies to handle them is beyond the scope. However, the vocabulary and its size is important for many NLP tasks, and different tokenization strategies typically yield very different types of vocabularies; as we will see next.

Overview to Basic Approaches¶

Character Tokenization¶

Character tokenization considers individual characters as tokens. In other words, this technique breaks down a sequence of characters simply into its individual characters. For example, the word "tokenization" would be tokenized into ["t", "o", "k", "e", "n", "i", "z", "a", "t", "i", "o", "n"*]. As there are no other considerations, character tokenization is very simple to implement. For example, in Python, the easiest way to accomplish this is to use the built-in list() function, which directly converts each character in the string to a list element.

text = "This is great"

tokens = list(text)

print(tokens)

['T', 'h', 'i', 's', ' ', 'i', 's', ' ', 'g', 'r', 'e', 'a', 't']

An alternative method is the use of a Regular Expression using the dot (.) is a special character that acts as a wildcard and matches any single character except a newline (\n) by default. Like shown before, we can use the findall() method of the re module to match all characters which are returned as a list of matches.

tokens = re.findall(r".", text)

print(tokens)

['T', 'h', 'i', 's', ' ', 'i', 's', ' ', 'g', 'r', 'e', 'a', 't']

Apart from its straightforward implementation, character tokenization also has other advantages. Character tokenization has several advantages that make it useful for certain tasks in Natural Language Processing (NLP). One major benefit is its simplicity and flexibility. Instead of breaking text into words or subwords, character tokenization splits it into individual characters. This makes it language-agnostic and especially helpful for languages without clear word boundaries, such as Chinese or Japanese. It can also handle uncommon words, typos, and unconventional spellings effectively since every possible word or symbol can be represented as a sequence of characters. Another advantage of character tokenization is that it avoids the out-of-vocabulary (OOV) problem. It eliminates this concern because it works with a small, fixed set of characters (like letters, numbers, and punctuation). This makes it particularly useful in tasks where new or rare words are common, such as when processing names, URLs, or code. Additionally, the smaller vocabulary size can simplify model training and storage requirements. However, while character tokenization is powerful, it typically requires more sophisticated models to learn meaningful patterns over longer sequences of characters.

Character tokenization, while flexible, has some significant disadvantages that can make it challenging to use effectively in Natural Language Processing (NLP). One major drawback is that it produces much longer sequences compared to word or subword tokenization. For example, a single word like "understanding" would become 13 separate tokens (one for each character). This increased sequence length means the model has to process more steps, which requires more memory and computational power. As a result, training and inference become slower and more resource-intensive. Another disadvantage is that characters alone carry very little semantic meaning. Unlike words or subwords, which often have clear meanings or associations, individual characters do not provide much information on their own. This makes it harder for the model to understand context or relationships between tokens. For example, understanding the word "run" from its characters ("r", "u", "n") requires the model to learn complex patterns across sequences of characters, which can make training more difficult and time-consuming. Additionally, character tokenization may struggle with languages that rely heavily on word boundaries or where context is crucial for meaning.

Word Tokenization¶

In simple terms, word tokenization treats each individual word as its own token, which was and still is one of the most common approaches to tokenize text. Even subword tokenization methods such as Byte-Pair Encoding involve some pretokenization step which is often done using basic word tokenization. Let's first create a list of sentences that will form our example document; some of the examples mimic social media content which is often not well-formed common English.

sentences = ["Text processing with Python is great.",

"It isn't (very) complicated to get started.",

"However,careful to...you know....avoid mistakes.",

"Contact me at alice@example.org; see http://example.org.",

"This is so cooool #nlprocks :))) :-P <3."]

To form the document, we can use the in-built join() method to concatenate all sentences using a white space as a separator.

document = ' '.join(sentences)

# Print the document to see if everything looks alright

print (document)

Text processing with Python is great. It isn't (very) complicated to get started. However,careful to...you know....avoid mistakes. Contact me at alice@example.org; see http://example.org. This is so cooool #nlprocks :))) :-P <3.

Word Tokenization with NLTK¶

NLTK (Natural Language Toolkit) provides multiple tokenizer implementations because tokenization is a fundamental yet complex task in natural language processing (NLP), and different tokenization methods are better suited to different types of text and use cases. Each tokenizer in NLTK is designed to handle specific challenges in text processing, such as punctuation, contractions, sentence boundaries, or domain-specific requirements. By offering various tokenizers, NLTK ensures flexibility and adaptability for users working with diverse languages, genres, and text formats.

For example, the TreebankWordTokenizer is ideal for tokenizing English text according to the Penn Treebank's guidelines, handling punctuation and contractions accurately. On the other hand, the PunktSentenceTokenizer is specifically designed to split text into sentences using a statistical model, making it highly effective for languages with complex sentence structures. Other tokenizers, like the RegexpTokenizer, allow users to define custom tokenization rules using regular expressions, giving them full control over the tokenization process. The existence of these different implementations allows users to select the most appropriate tokenizer based on the characteristics of the input text and the specific requirements of their NLP tasks. Furthermore, language and context can influence the choice of tokenizer. For instance, tokenizers like WordPunctTokenizer can split text into words and punctuation marks, making it suitable for applications where punctuation plays a significant role. NLTK's wide range of tokenizers caters to various needs, from simple word tokenization to more sophisticated sentence and subword segmentation, ensuring that users can perform tokenization effectively, regardless of the complexity or domain of the text.

PunktSentenceTokenizer¶

The PunktSentenceTokenizer is a pre-trained tokenizer used to split a text into sentences. It is based on the Punkt sentence segmentation algorithm, which is a statistical model for sentence boundary detection. The model works by analyzing patterns in the text, such as punctuation marks and capitalization, to determine where sentences start and end.

sentence_tokenizer = PunktSentenceTokenizer()

# The tokenize() method returns a list containing the sentences

sentences_alt = sentence_tokenizer.tokenize(document)

# Loop over all sentences and print each sentence

for s in sentences_alt:

print (s)

Text processing with Python is great. It isn't (very) complicated to get started. However,careful to...you know....avoid mistakes. Contact me at alice@example.org; see http://example.org. This is so cooool #nlprocks :))) :-P <3.

While this seems like a trivial task, appreciate that particularly the period character (.) has many other uses beyond marking the end of a sentence. For example, the period may be used in URLs or email addresses, as part of ellipses (...), or as a decimal point in numbers. Furthermore, simple rules such as "a period marks the end of a sentence if it is followed by white space character, and the next letter must be a capital letter" may often fail in practice as there are many exceptions and users might have typed sentences that do not adhere to proper orthographic rules.

NLTKWordTokenizer¶

The NLTKWordTokenizer is specifically designed to handle common tokenization challenges, such as punctuation, contractions, and special characters. For example, it can correctly separate punctuation marks (e.g., splitting "Hello, world!" into ["Hello", ",", "world", "!"]) and handle contractions (e.g., splitting "don't" into ["do", "n't"]). Internally, the NLTKWordTokenizer uses regular expressions to define rules for splitting text. It is also the default tokenizer used by the method word_tokenize().

nltk_word_tokenizer = NLTKWordTokenizer()

print ("Output of NLTKWordTokenizer:")

for s in sentences:

print (nltk_word_tokenizer.tokenize(s))

print()

print ("Output of the word_tokenize() method:")

for s in sentences:

print (word_tokenize(s))

Output of NLTKWordTokenizer:

['Text', 'processing', 'with', 'Python', 'is', 'great', '.']

['It', 'is', "n't", '(', 'very', ')', 'complicated', 'to', 'get', 'started', '.']

['However', ',', 'careful', 'to', '...', 'you', 'know', '....', 'avoid', 'mistakes', '.']

['Contact', 'me', 'at', 'alice', '@', 'example.org', ';', 'see', 'http', ':', '//example.org', '.']

['This', 'is', 'so', 'cooool', '#', 'nlprocks', ':', ')', ')', ')', ':', '-P', '<', '3', '.']

Output of the word_tokenize() method:

['Text', 'processing', 'with', 'Python', 'is', 'great', '.']

['It', 'is', "n't", '(', 'very', ')', 'complicated', 'to', 'get', 'started', '.']

['However', ',', 'careful', 'to', '...', 'you', 'know', '....', 'avoid', 'mistakes', '.']

['Contact', 'me', 'at', 'alice', '@', 'example.org', ';', 'see', 'http', ':', '//example.org', '.']

['This', 'is', 'so', 'cooool', '#', 'nlprocks', ':', ')', ')', ')', ':', '-P', '<', '3', '.']

Both outputs are the same, since the word_tokenize() method is just a wrapper for the NLTKWordTokenizer to simplify the coding. In general, this tokenizer performs great on well-formed English text. However, it performs rather poorly for non-standard tokens such as URLs, email addresses, hashtags, emoticons, etc. This means that this tokenizer might not be the best choice for user-generated text data such as social media or forum posts.

TreebankWordTokenizer¶

The TreebankWordTokenizer is designed to tokenize text according to the conventions of the Penn Treebank. The Penn Treebank is a widely used corpus of annotated English text that has been extensively used in natural language processing research. The TreebankWordTokenizer tokenizes text by following the rules and conventions defined in the Penn Treebank. It splits text into words and punctuation marks while considering specific cases such as contractions, hyphenated words, and punctuation attached to words. It is the default tokenizer of NLTK. This tokenizer is commonly used for tasks that rely on the Penn Treebank tokenization conventions, such as training and evaluating language models, part-of-speech tagging, syntactic parsing, and other NLP tasks that benefit from consistent tokenization based on the Penn Treebank guidelines.

treebank_tokenizer = TreebankWordTokenizer()

print ("Output of TreebankWordTokenizer:")

for s in sentences:

print (treebank_tokenizer.tokenize(s))

Output of TreebankWordTokenizer:

['Text', 'processing', 'with', 'Python', 'is', 'great', '.']

['It', 'is', "n't", '(', 'very', ')', 'complicated', 'to', 'get', 'started', '.']

['However', ',', 'careful', 'to', '...', 'you', 'know', '...', '.avoid', 'mistakes', '.']

['Contact', 'me', 'at', 'alice', '@', 'example.org', ';', 'see', 'http', ':', '//example.org', '.']

['This', 'is', 'so', 'cooool', '#', 'nlprocks', ':', ')', ')', ')', ':', '-P', '<', '3', '.']

Notice how the tokenizer can handle the ellipsis (...) correctly in the first case but fails in the second case since an ellipsis is by definition composed of exactly 3 dots. More or less the 3 dots are not handled properly. Like the NLTKWordTokenizer, the TreebankWordTokenizer also has troubles with non-standard tokens (URLs, email addresses, hashtags, emoticons, etc.)

TweetTokenizer¶

The TweetTokenizer is a specific tokenizer designed for tokenizing tweets or other social media text. It is tailored to handle the unique characteristics and conventions often found in tweets, such as hashtags, user mentions, emoticons, and URLs. It offers additional functionality compared to general-purpose tokenizers. It takes into account the specific structures and symbols commonly used in tweets, allowing for more accurate and context-aware tokenization of social media text. It recognizes and tokenizes hashtags, user mentions (starting with "@"), URLs, emoticons, and other patterns commonly found in tweets, providing a more fine-grained tokenization approach for analyzing social media text.

tweet_tokenizer = TweetTokenizer()

print ("Output of TweetTokenizer:")

for s in sentences:

print (tweet_tokenizer.tokenize(s))

Output of TweetTokenizer:

['Text', 'processing', 'with', 'Python', 'is', 'great', '.']

['It', "isn't", '(', 'very', ')', 'complicated', 'to', 'get', 'started', '.']

['However', ',', 'careful', 'to', '...', 'you', 'know', '...', 'avoid', 'mistakes', '.']

['Contact', 'me', 'at', 'alice@example.org', ';', 'see', 'http://example.org', '.']

['This', 'is', 'so', 'cooool', '#nlprocks', ':)', ')', ')', ':-P', '<3', '.']

The TweetTokenizer recognizes (most) URLs, email addresses, hashtags, and common emoticons as their own tokens. It kind of fails for less common emoticons such as :))). The problem is that it is not the "official version" of the emoticon — which is :) or :-) — but uses multiple "mouths" to emphasize the expressed sentiment of feeling. This indicates that the TweetTokenizer uses some form of predefined dictionaries for identifying emoticons. However, if a subsequent analysis does not really depend on it, some extra ) are no big deal in many cases. For example, in case of sentiment analysis, if it is only important if an emoticon is a positive emoticon or a negative emoticon, the tokenizer result above would be sufficient.

RegexpTokenizer¶

The RegexpTokenizer is a customizable tokenizer that uses regular expressions to split text into tokens based on specified patterns. It allows you to define a regular expression pattern that matches the desired token boundaries. It tokenizes text by identifying substrings that match the specified pattern and separating them into individual tokens. You can customize the regular expression pattern according to your specific tokenization requirements. For example, if you want to tokenize based on specific characters, you can modify the pattern accordingly. Additionally, you can use character classes, quantifiers, and other regular expression constructs to define more complex tokenization patterns. The RegexpTokenizer provides flexibility and fine-grained control over the tokenization process. It allows you to adapt the tokenizer to the specific needs of your text data and the requirements of your NLP task. By defining appropriate regular expression patterns, you can tokenize text in a way that suits your specific use case, such as handling specialized domains, custom abbreviations, or other text patterns.

Your turn: In the code below, try different patterns to see how it affects the tokenization results. Apart from trying the different patterns given, you can also write your own pattern to get even better results.

#pattern = '\w+' # all alphanumeric words

#pattern = '[a-zA-Z]+' # all alphanumeric words (without digits)

pattern = '[a-zA-Z\']+' # all alphanumeric words (without digits, but keep contractions)

regexp_tokenizer = RegexpTokenizer(pattern)

print (f"Output of RegexpTokenizer for pattern {pattern}:")

for s in sentences:

print (regexp_tokenizer.tokenize(s))

Output of RegexpTokenizer for pattern [a-zA-Z']+: ['Text', 'processing', 'with', 'Python', 'is', 'great'] ['It', "isn't", 'very', 'complicated', 'to', 'get', 'started'] ['However', 'careful', 'to', 'you', 'know', 'avoid', 'mistakes'] ['Contact', 'me', 'at', 'alice', 'example', 'org', 'see', 'http', 'example', 'org'] ['This', 'is', 'so', 'cooool', 'nlprocks', 'P']

Word Tokenization with spaCy¶

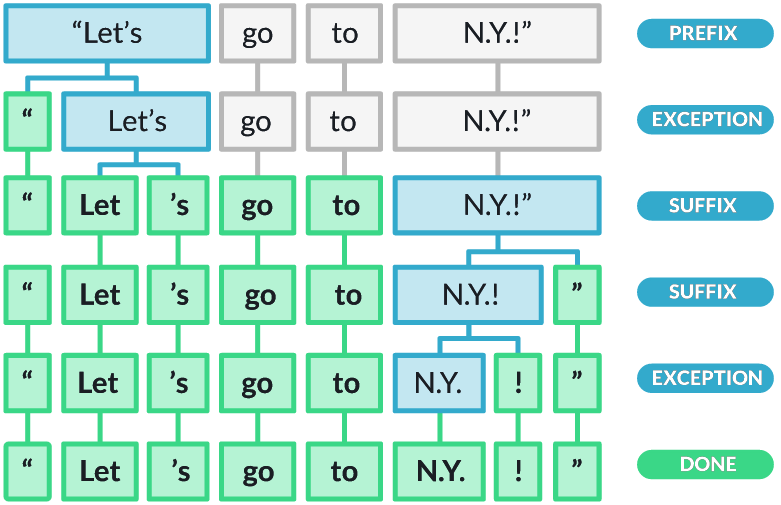

The spaCy tokenizer is a highly efficient and accurate tokenizer used in the spaCy NLP library, designed to split text into words, punctuation, and other meaningful units. What makes spaCy's tokenizer special is its combination of speed, flexibility, and linguistic accuracy, providing an advanced tokenization system that works well for multiple languages and complex texts. spaCy’s tokenizer uses a combination of rule-based methods and statistical models. It incorporates rules for handling punctuation, contractions, and special cases like email addresses or numbers. Additionally, spaCy uses machine learning models trained on large corpora, allowing the tokenizer to accurately handle edge cases such as abbreviations, hyphenated words, and names. Here's a general overview of how the tokenizer in spaCy works:

Whitespace Splitting: The tokenizer initially splits the text on whitespace characters (e.g., spaces, tabs, newlines) to create token candidates.

Prefix Rules: The tokenizer applies a set of prefix rules to identify and split off leading punctuation marks, such as opening quotation marks or brackets. For example, the tokenizer would split "Hello!" into two tokens, "Hello" and "!".

Suffix Rules: Similarly, the tokenizer applies suffix rules to identify and split off trailing punctuation marks, such as periods or closing quotation marks. For example, it would split "example." into two tokens, "example" and ".".

Infixes: The tokenizer then looks for infixes, which are sequences of characters that appear within a word. It uses rules to determine where to split these infixes, typically when they indicate word boundaries. For instance, the tokenizer would split "can't" into "ca" and "n't".

Special Cases: spaCy's tokenizer handles special cases, such as contractions, abbreviations, emoticons, or currency symbols, where the standard rules might not apply. It uses language-specific knowledge and a customizable list of special case rules to tokenize these instances correctly.

Tokenization Exceptions: spaCy provides a mechanism to define exceptions to the tokenization rules using custom tokenization patterns. This allows users to override the default behavior and handle specific cases according to their needs.

Post-processing: After applying the tokenization rules, the tokenizer performs additional post-processing steps. This may involve removing leading or trailing white spaces, normalizing Unicode characters, or applying language-specific transformations.

The figure below illustrates the tokenization process by applying the different rules and heuristics. This image is directly take from the spaCy website:

spaCy's tokenizer is designed to be highly customizable and can be trained or adjusted to accommodate specific domain requirements or languages. It forms the foundation for many subsequent natural language processing tasks, such as part-of-speech tagging, named entity recognition, and dependency parsing. Compared to NLTK, the common usage of spaCy is to process a string which not only performs tokenization but also other steps (see later tutorial). Here, we only look at the tokens. Again, we process each sentence individually to simplify the output.

print ("Output of spaCy tokenizer:")

for s in sentences:

token_list = [ token.text for token in nlp(s) ]

print (token_list)

Output of spaCy tokenizer:

['Text', 'processing', 'with', 'Python', 'is', 'great', '.']

['It', 'is', "n't", '(', 'very', ')', 'complicated', 'to', 'get', 'started', '.']

['However', ',', 'careful', 'to', '...', 'you', 'know', '....', 'avoid', 'mistakes', '.']

['Contact', 'me', 'at', 'alice@example.org', ';', 'see', 'http://example.org', '.']

['This', 'is', 'so', 'cooool', '#', 'nlprocks', ':)))', ':-P', '<3', '.']

spaCy does a bit better with the uncommon emoticon, but it splits the hashtag. However, spaCy allows you to customize the rules and heuristics better suit your specific requirements, typically given by your taks your application.

Discussion¶

Word tokenization is a well established task, particularly for popular languages such as English, German, French, Spanish, Chinese, and so on. One of the primary benefits of word tokenization is that it aligns closely with the natural linguistic structure of most languages. Since words are the fundamental units of meaning in human communication, tokenizing by words preserves the semantic integrity of the text. Another advantage of word tokenization is its simplicity and efficiency. It results in fewer tokens compared to character tokenization, which splits words into their individual characters, or subword tokenization, which might break words into smaller subword units. Since fewer tokens are generated, word tokenization leads to shorter input sequences, which translates into less computational overhead for the model during both training and inference. Compared to subword tokenization, which may break words into smaller units (like prefixes, suffixes, or parts of a word), word tokenization avoids the potential loss of meaning when breaking down a word into pieces. While subword tokenization is useful for handling out-of-vocabulary (OOV) words, word tokenization ensures that the model can directly work with the entire word as a meaningful token. This can lead to faster training times since the model does not need to learn the combinations of subword units but rather the full word itself. It also reduces the complexity of the model, as it does not need to learn the intricacies of word formation through smaller components.

While word tokenization is effective in many cases, it does have several disadvantages. One of the main drawbacks is that the resulting vocabulary after tokenizing a text corpus can be very large. For example the number of unique words/tokens that appear in at least 3 Wikipedia articles is estimated to be around 2,75 million. Even when considering the most frequent tokens, vocabulary sizes of several tens or hundreds of thousand tokens are very common. This includes that word tokenization is less flexible in handling morphologically rich languages where a single word may represent multiple variations (e.g., "run", 'running", "ran" or "houses", "house's", "house"). Word tokenization struggles to capture these variations, leading to an inflated vocabulary and potential inefficiency, especially if the model needs to account for every possible form of a word. This also increases the risk of OOV tokens when using models trained on word-tokenized text. Lastly, Word tokenization also has limitations in languages that lack clear word boundaries or have ambiguous segmentation, such as Chinese or Japanese, where words are not separated by spaces.

Subword Tokenization¶

The basic idea behind subword tokenization is to break text into smaller, meaningful units that are larger than individual characters but smaller than entire words. It aims to find a balance between word tokenization (which splits text into complete words) and character tokenization (which splits text into individual characters). Subword tokenization focuses on splitting words into smaller pieces, such as prefixes, suffixes, or commonly occurring subword units, which can be combined to form a complete word. This technique allows models to handle a wider variety of words while keeping the vocabulary size manageable.

The main characteristic of subword tokenization — compared to character and word tokenization — is that the vocabulary and where to split the string is learned based on a large training corpus, instead of simple pattern matching or predefined rules. In a nutshell, the more frequently a substring appears in the corpus, the more likely it is considered to be a token in final vocabulary. There exists a wide range of subword tokenization techniques; here is a brief overview:

Byte Pair Encoding (BPE): BPE starts with a vocabulary of all individual characters that occur in the training corpus. It then iteratively merges the most frequent pairs of tokens (starting with characters) into new subword units until a desired vocabulary size is reached. This means the BPE allows to specify the size of the final vocabulary, and it can handle rare and unseen words (i.e., OOV tokens) by splitting them into subwords.

WordPiece: WordPiece works similar to BPE, but instead of merging pairs based on frequency, it selects merges that maximize the likelihood of the training corpus. It is therefore more suited for likelihood-based language modeling and widely used in pretrained models like BERT. For example, WordPiece might "playing" into "play" and "##ing", where "##" indicates a continuation subword).

Unigram Language Model (ULM): In contrast to BPE or WordPiece, ULM initializes its base vocabulary to a large number of symbols and progressively trims down each symbol to obtain a smaller vocabulary. The base vocabulary could for instance correspond to all pre-tokenized words and the most common substrings. Unigram is not used directly for any of the models in the transformers, but it is used in conjunction with SentencePiece.

SentencePiece: SentencePiece is a text tokenizer and detokenizer that implements subword tokenization without requiring prior word-based segmentation. SentencePiece works by applying one of two main algorithms: Byte Pair Encoding (BPE) or the Unigram Language Model. Both methods iteratively build a subword vocabulary optimized for the dataset. The Unigram Language Model, for example, assigns probabilities to subwords and prunes less probable ones to maximize the likelihood of the data. This makes it highly versatile for multilingual tasks and robust in handling rare or out-of-vocabulary words.

Morpheme-Based Tokenization: Morpheme-Based Tokenization splits words into their smallest meaningful linguistic units called morphemes. This approach is particularly beneficial for morphologically rich languages like Turkish, Finnish, or Arabic, where words often contain multiple morphemes that express grammatical and semantic information. Morpheme-based tokenization typically involves linguistic analysis and relies on morphological parsers or rule-based systems. For example, the word "unhappiness" might be split into un- (prefix), happy (root), and -ness (suffix). This decomposition enables NLP models to capture the underlying semantics and grammar more effectively. While accurate, morpheme-based tokenization can be computationally intensive and may require specialized resources or language-specific rules, making it less common in general-purpose NLP systems compared to subword tokenization methods like BPE.

| Technique | Key Feature | Common Usage |

|---|---|---|

| BPE | Frequency-based merging | GPT, Transformers |

| WordPiece | Likelihood-based merging | BERT, XLNet |

| Unigram | Probabilistic model | T5, SentencePiece |

| SentencePiece | No pre-tokenization needed | Multilingual models |

| Morpheme-Based | Linguistic insights | Morphologically rich languages |

To be effective, subword tokenizers required training over a large text corpora. Many such pretrained tokenizer models are publicly available and can be used with very little code. The AutoTokenizer class in the Hugging Face transformers library is a versatile and user-friendly utility that automatically selects the appropriate tokenizer for a given pre-trained model.

# Choose pretrained tokenizer model

tokenizer_model_name = "gpt2" # BPE

#tokenizer_model_name = "bert-base-uncased" # WordPiece

#tokenizer_model_name = "t5-small" # SentencePiece

# Load a pretrained tokenizer

tokenizer = AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained(tokenizer_model_name)

Once the tokenizer model is loaded, it can be used to tokenize any text according to its learned vocabulary. The default output of the tokenizer is not the list of tokens but their respective ids according to the vocabulary. This is more practical as these sequences of ids can directly serve as input for machine learning models that expect numerical inputs (which are most of them incl. neural networks). To convert those ids to actual readable tokens, we can use the convert_ids_to_tokens() method. The code cell below shows a simple example:

# Encode text into token IDs

encoded = tokenizer("Most fossils of Tyrannosaurus rex fall into the Cretaceous period.")

print(f"Token IDs: {encoded['input_ids']}")

print(f"Tokens: {tokenizer.convert_ids_to_tokens(encoded['input_ids'])}")

Token IDs: [6943, 34066, 286, 38401, 47650, 302, 87, 2121, 656, 262, 327, 1186, 37797, 2278, 13] Tokens: ['Most', 'Ġfossils', 'Ġof', 'ĠTyrann', 'osaurus', 'Ġre', 'x', 'Ġfall', 'Ġinto', 'Ġthe', 'ĠC', 'ret', 'aceous', 'Ġperiod', '.']

Depending on the chosen tokenizer model, the list of resulting tokens is likely to differ. But generally, common words will form their own token, while more rare words are likely to be split into multiple tokens. You will also notice that different models use different special characters at the beginning or end of tokens. Those special characters are required so the model can tell if two adjacent tokens do belong together or represent separate words.

Summing up, subword tokenization bridges the gap between word-level and character-level tokenization, providing an effective balance for handling diverse languages, rare words, and efficient model training. One of the main strengths is its ability to break rare or unseen words into smaller, meaningful subword units. This ensures that even if the entire word is not in the vocabulary, the model can still understand its meaning by interpreting the subwords. Unlike word tokenization, which requires a huge vocabulary to cover all possible words, subword tokenization significantly reduces the vocabulary size by reusing subword units across different words. A smaller vocabulary leads to faster computations, less memory usage, and better generalization across languages and datasets. In languages like Turkish, Finnish, or Arabic, words are often formed by combining roots, prefixes, and suffixes, resulting in a vast number of unique words. Subword tokenization handles these languages effectively by splitting words into smaller units that still retain meaning, such as the root and affixes. It also can make NLP systems more resilient to typos, abbreviations, or informal text. This robustness is particularly valuable in real-world applications like social media analysis and customer support systems. Lastly, subword tokenization techniques, such as Byte Pair Encoding (BPE) or Unigram Language Model, work across different languages without relying on language-specific rules.

However, subword tokenization has some disadvantages that can affect its performance in certain NLP tasks. For one, it can make it harder to interpret the results of a model. Since words are split into smaller units, it may not be immediately clear how the model understands a word or phrase. Breaking words into subwords can also increase the total number of tokens in a sentence. This results in longer input sequences, which can slow down processing and increase computational costs. Models with fixed input limits, like BERT (typically 512 tokens), may struggle with longer texts when subword tokenization is applied. Most obviously, subword tokenization relies on the vocabulary learned from the training data. If the training data is not representative of the real-world usage, the resulting subword vocabulary may miss important patterns or create inefficiencies. Subword tokenization may also add ambiguity , for example, the same subword can appear in different contexts with different meanings. Lastly, in languages like Chinese, where words are already short or consist of single characters, subword tokenization offers limited benefits. Additionally, for English, where most words are relatively short and frequent, the need to break them into subwords can introduce unnecessary complexity without significant gains.

Summary¶

Tokenization is the process of dividing text into smaller units, known as tokens, which could be words, phrases, or subwords. It serves as the first step in preparing text data for natural language processing tasks, converting unstructured text into a structured format that algorithms can analyze. Tokens are the building blocks for a wide range of NLP applications, such as text classification, sentiment analysis, and machine translation, making tokenization a critical step in understanding and processing human language.

There are several tokenization techniques, each suited to different languages and use cases. Word tokenization, one of the most common methods, involves splitting text based on spaces and punctuation to produce individual words. However, this approach may struggle with contractions (e.g., "don't") or compound words. Subword tokenization, such as Byte Pair Encoding (BPE) or WordPiece, is designed to handle rare or unknown words by breaking them into smaller, meaningful units like prefixes, suffixes, or character sequences. This technique is particularly effective for languages with rich morphology or large vocabularies. Character-level tokenization, which treats each character as a token, offers high flexibility but may result in longer sequences, increasing computational complexity.

The choice of tokenization method significantly impacts NLP models. For example, traditional models like Bag of Words or TF-IDF require word-level tokenization to create vectorized representations of text. Meanwhile, modern transformer-based models, such as BERT and GPT, often rely on subword tokenization to balance vocabulary size and generalizability. Additionally, multilingual NLP models benefit from tokenization techniques that account for cross-linguistic variations, ensuring consistent handling of text in multiple languages.

Tokenization is crucial because it directly influences the accuracy, efficiency, and contextual understanding of NLP models. Poorly tokenized data can lead to loss of meaning, reduced model performance, and higher computational costs. Conversely, well-executed tokenization enhances model comprehension of context, improves handling of rare or unseen words, and facilitates robust training on diverse datasets. By adapting tokenization strategies to specific languages and tasks, NLP practitioners can maximize the effectiveness of their models and achieve better outcomes in real-world applications.