Disclaimer: This Jupyter Notebook contains content generated with the assistance of AI. While every effort has been made to review and validate the outputs, users should independently verify critical information before relying on it. The SELENE notebook repository is constantly evolving. We recommend downloading or pulling the latest version of this notebook from Github.

Building a Word Tokenizer from Scratch¶

Motivation¶

Word tokenization is a foundational process in natural language processing (NLP) that involves breaking down a text into smaller units, typically words or subwords. This step is critical as it prepares the text for further linguistic or statistical analysis, such as part-of-speech tagging, sentiment analysis, or machine translation. By converting text into manageable pieces, tokenization serves as the gateway for machines to understand and process human language. Despite its apparent simplicity, tokenization can be surprisingly complex due to the intricate nature of human languages.

One of the primary challenges in word tokenization is handling the diversity of linguistic rules and writing systems across different languages. For instance, in English, spaces generally delineate words, making tokenization relatively straightforward. However, even in English, ambiguities arise with contractions (e.g., "don't"), possessives, and hyphenated words (e.g., "state-of-the-art"). Languages like Chinese, Japanese, and Thai, which lack explicit word delimiters, require sophisticated algorithms or statistical models to accurately identify word boundaries. Furthermore, agglutinative languages like Finnish or Turkish, where words are formed by appending multiple morphemes, add another layer of complexity.

Another significant challenge lies in dealing with informal text, such as social media posts, where grammatical rules are often disregarded. Slang, emojis, hashtags, and abbreviations (e.g., "LOL" or "u r gr8") can disrupt conventional tokenization methods. For example, "New York-based" could be treated as one or multiple tokens depending on the tokenizer, leading to inconsistencies. Additionally, tokenizers must handle punctuation carefully, deciding whether to attach it to a word or treat it as a separate token, which can impact downstream NLP tasks.

Advancements in tokenization methods, such as byte-pair encoding (BPE) and subword tokenization (used in models like BERT and GPT), have addressed some of these challenges. These techniques allow models to tokenize rare or out-of-vocabulary words into smaller meaningful units, enabling better representation and understanding. Despite these innovations, tokenization remains a critical topic in NLP, as its effectiveness directly impacts the performance of downstream tasks. Understanding its challenges ensures robust and accurate language models, essential for applications in translation, sentiment analysis, and conversational AI.

In this notebook, we will build a basic word tokenizer for English text from scratch. This tokenizer is not intended to compete with existing solutions from popular libraries and tools but to serve for educational purposes — and take a look a bit "under the hood" how existing tokenizers work.

Setting up the Notebook¶

Make Required Imports¶

This notebook requires the import of different Python packages but also additional Python modules that are part of the repository. If a package is missing, use your preferred package manager (e.g., conda or pip) to install it. If the code cell below runs with any errors, all required packages and modules have successfully been imported.

from src.utils.libimports.tokenizing import *

from src.text.preprocessing.tokenizing import MyWordTokenizer

Preliminaries¶

Purpose & Scope¶

Natural language, incl. English is very expressive and allows for a large degree of variation. Building a state-of-the-art tokenizer is therefore a challenging task. As such, our goals is simply to build a decent tokenizer and not a perfect tokenizer (if such a thing even exists). We focus on the most common orthographic, morphological, and punctuation rules for the tokenization process. Thus, it will be very easy to create sentences where our tokenizer will perform poorly. This also includes that there are no (serious) considerations regarding runtime performance. The purpose of this implementation is educational to see how tokenizers of popular libraries work. This can be very useful in practice when you have to work with a very domain-specific language where a general-purpose tokenizer might now be suitable.

Basic Assumptions¶

We assume the input text to be (reasonably) well-formed English. This includes that the text adheres common orthographic rules, particularly when it comes to word boundaries, punctuation, and hyphenation. For example, that punctuation marks are always correctly followed by white space character (or the punctuation mark is the last character). This assumption is important as our tokenizer starts by splitting a text by white space characters; see below. For editorial and (semi-)profession content, this assumption is very likely to hold, but user-generated content on social media or similar may often not be well-formed text.

Alignment¶

When it comes to tokenization and what constitutes an individual token, there is no single well-defined set of rules. While word tokenization basically implies that each word forms a token, things a less obvious in case of, for example, hyphenated words (e.g., "well-written", "mother-in-law") or contractions (e.g., "I'm", "should've", "can't"). Other non-obvious decisions on how to handle them relate to non-standard tokens such as URLs, email addresses, hashtags, emoticons, etc. For consistency, we therefore roughly align the output of our tokenizer with the provided by spaCy. The spaCy tokenizer is a highly efficient and accurate tokenizer used in the spaCy NLP library, designed to split text into words, punctuation, and other meaningful units. The tokenizer initially splits the text on whitespace characters (e.g., spaces, tabs, newlines) to create token candidates. It then recursively applies various rules to each token to check if a token needs to be split.

Our tokenizer will follow the same principle. Notice how this assumes a language like English that relies heavily on white spaces to indicate word/token boundaries. Still, our tokenizer and the spaCy tokenizer are likely to yield different results, even for similar aspects since the rules of the spaCy tokenizer will be more refined to handle more special cases.

With these clarifications out of the way, let's get started building our tokenizer.

Implementation¶

Throughout the notebook, we will use a series of example sentences to observe how our tokenizer performs. The code cell below contains five example sentences, as well as their respective results after applying the spaCy tokenizer. This is to give you a first idea how common off-the-shelf tokenizers behave (e.g., in case of contractions, hyphenated words, parentheses, etc.)

text1 = "Let's go to N.Y. to visit my mother-in-law!!! It'll be great, I'm sure."

text2 = "I've got an appointment with Dr. Smith...I hope it won't be bad."

text3 = "Please select your answer: A (luggage) or B (no luggage)."

text4 = "My website is www.example.com (email: user@example.com) #contact."

text5 = "The ambience was :o))), but the food was )-:"

print([token.text for token in nlp(text1)])

print([token.text for token in nlp(text2)])

print([token.text for token in nlp(text3)])

print([token.text for token in nlp(text4)])

print([token.text for token in nlp(text5)])

['Let', "'s", 'go', 'to', 'N.Y.', 'to', 'visit', 'my', 'mother', '-', 'in', '-', 'law', '!', '!', '!', 'It', "'ll", 'be', 'great', ',', 'I', "'m", 'sure', '.']

['I', "'ve", 'got', 'an', 'appointment', 'with', 'Dr.', 'Smith', '...', 'I', 'hope', 'it', 'wo', "n't", 'be', 'bad', '.']

['Please', 'select', 'your', 'answer', ':', 'A', '(', 'luggage', ')', 'or', 'B', '(', 'no', 'luggage', ')', '.']

['My', 'website', 'is', 'www.example.com', '(', 'email', ':', 'user@example.com', ')', '#', 'contact', '.']

['The', 'ambience', 'was', ':o)', ')', ')', ',', 'but', 'the', 'food', 'was', ')-:']

While the goal of our implementation is not to perfectly match the output of the spaCy tokenizer, it will serve as some general guideline for a design decision.

Your turn: Throughout the notebook, you are welcome to add your own text examples, as well as modify the implementation towards an improved version of the tokenizer. The provided token splitting rules and exceptions are kept reasonably simple on purpose to ease the understanding. You can modify those rules and exceptions (or add your own new rules and exceptions) and see how it affects the behavior of your tokenizer. This is a very good practice to better appreciate the core ideas and challenges when it comes to tokenizing text documents.

Basic Algorithm¶

The core algorithm of our tokenizer is implemented by the class MyTokenizer in the file src.tokenizer. This class has only two methods:

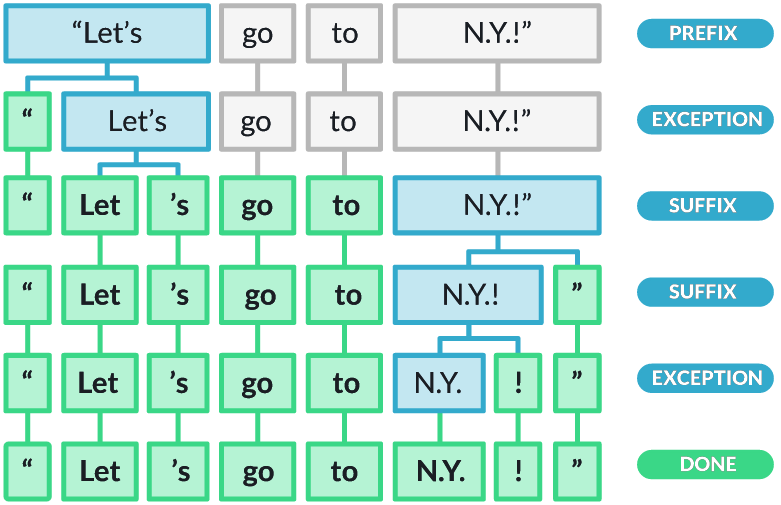

tokenize(): This method takes a string as input and returns the final list of tokens by performing two main steps.- The method splits the input string by white space characters to yield the initial list of tokens.

- The method then checks each token if a further split is needed using the method

_apply_splitting_rules(). If a token was split into new smaller tokens, those tokens are again checked if they should be split. This process continues until no token in the current list of tokens requires any more splitting.

_apply_splitting_rules(): This method checks if a token needs to be split by applying a given set of rules (e.g., splitting punctuation marks and the end of a token). Apart from the set of rules, this method also takes in a set of exceptions to avoid any split. We will see during the implementation while this separation between rules and exceptions is more convenient through the implementation.

Appreciate that the class MyTokenizer itself contains very little code. All the heavy lifting is done by the implementation of the rules and the exceptions, which will be the focus throughout the rest of the notebook.

my_tokenizer = MyWordTokenizer()

print(my_tokenizer.tokenize(text1))

print(my_tokenizer.tokenize(text2))

print(my_tokenizer.tokenize(text3))

print(my_tokenizer.tokenize(text4))

print(my_tokenizer.tokenize(text5))

["Let's", 'go', 'to', 'N.Y.', 'to', 'visit', 'my', 'mother-in-law!!!', "It'll", 'be', 'great,', "I'm", 'sure.'] ["I've", 'got', 'an', 'appointment', 'with', 'Dr.', 'Smith...I', 'hope', 'it', "won't", 'be', 'bad.'] ['Please', 'select', 'your', 'answer:', 'A', '(luggage)', 'or', 'B', '(no', 'luggage).'] ['My', 'website', 'is', 'www.example.com', '(email:', 'user@example.com)', '#contact.'] ['The', 'ambience', 'was', ':o))),', 'but', 'the', 'food', 'was', ')-:']

Token Splitting Rules¶

In general, a token splitting rule is a condition to check if a given token needs to be split. If so, the rule splits the token and into a list of subtokens. Each rule is implemented as a method which takes a token as input and returns a tuple containing two values as output. The first value is either True (split performed) or False (no split performed) and the list of subtokens in case the token has been split. The pseudo code below shows the basic structure of a method implementing a splitting rule.

def split(token):

if <split_condition> == True:

return (True, [subtoken1, subtoken2, ...])

else:

return (False, [])

A rule may split a token into two or more subtokens depending on the condition. Recall that after a split, each new subtoken will again be checked with respect to all implemented rules until no rule will result in any further split of any token.

Basic Punctuation Marks¶

By the convention of most writing styles punctuation marks (e.g., a period, comma, or question mark) is followed by a whitespace character — assuming the punctuation mark is not the last character in a string — but not preceded by a whitespace character. This convention is rooted in the history and purpose of punctuation in written language. Here are some commonly cited the main reasons:

Visual clarity: Punctuation marks indicate the structure and rhythm of sentences. Placing whitespace after punctuation creates a clear separation between sentences or clauses, improving readability. Adding whitespace before punctuation would disrupt the flow of text and make it visually inconsistent.

Linguistic rules: In most writing systems, punctuation marks are tied closely to the words they modify (for example, correct: "I love books.", incorrect: "I love books .") By keeping punctuation marks adjacent to the relevant word, the meaning is preserved and unambiguous.

Historical typesetting: In traditional typesetting and printing, punctuation marks were designed to be visually attached to the preceding word. A whitespace character was placed after punctuation to create a pause and facilitate easier reading. Early mechanical typesetting (e.g., movable type) reinforced this convention because it aligned well with how text was laid out efficiently.

Digital text formatting: Computers and software rely on established rules of spacing for proper word wrapping and alignment. Adding whitespace characters after punctuation but not before ensures consistent behavior across platforms and formats.

Over centuries, these conventions became deeply ingrained in grammar and style guides across languages that use alphabets. Writers and readers are now accustomed to these rules as a standard. That being said, some languages, such as French, have specific rules for punctuation spacing. For example, in French typography, a space is added before certain punctuation marks like colons, question marks, and exclamation points. By adhering to this convention, texts maintain a balance of aesthetic and functional readability.

Of course, not having a whitespace character before a punctuation mark means that simply splitting a text with respect to whitespaces fails to split punctuation marks from preceding words (or tokens, in general). We therefore need a rule to split punctuation marks from the end of a token, if present. For most punctuation marks (e.g., question mark, exclamation mark, comma, colon, semicolon), this is a rather straightforward rule. However, this is more challenging for periods as this character has many other users. We therefore exclude the period character for this basic rule to handle it separately.

To check if the last character of a token is a punctuation mark (excluding the period), we use the following simple Regular Expression: (?:.+)([,:;?!]{1})$. It matches any sequence of characters that starts with a non-empty sequence of characters and ends with a punctuation mark. The expression is organized into two groups, one capturing everything before the punctuation mark, the other the punctuation mark itself. This makes extracting the two subtokens as result from the split very easy. The method split_basic_punctuation() implementing this rule looks as follows:

def split_basic_punctuation(token):

subtokens = []

# Common Punctuation marks (word followed by a single punctuation mark -- except ".")

for match in re.finditer(r"(.+)([,:;?!]{1})$", token, flags=re.IGNORECASE):

subtokens.append(match[1])

subtokens.append(match[2])

return True, subtokens

return False, []

Let's apply this first rule when tokenizing our example sentences:

rules = [split_basic_punctuation]

print(my_tokenizer.tokenize(text1, rules=rules))

print(my_tokenizer.tokenize(text2, rules=rules))

print(my_tokenizer.tokenize(text3, rules=rules))

print(my_tokenizer.tokenize(text4, rules=rules))

print(my_tokenizer.tokenize(text5, rules=rules))

["Let's", 'go', 'to', 'N.Y.', 'to', 'visit', 'my', 'mother-in-law', '!', '!', '!', "It'll", 'be', 'great', ',', "I'm", 'sure.'] ["I've", 'got', 'an', 'appointment', 'with', 'Dr.', 'Smith...I', 'hope', 'it', "won't", 'be', 'bad.'] ['Please', 'select', 'your', 'answer', ':', 'A', '(luggage)', 'or', 'B', '(no', 'luggage).'] ['My', 'website', 'is', 'www.example.com', '(email', ':', 'user@example.com)', '#contact.'] ['The', 'ambience', 'was', ':o)))', ',', 'but', 'the', 'food', 'was', ')-', ':']

We see some first improvements. Now all punctuation marks (except the period) are their separate tokens. Notice that the rule could also handle the cases of repeated punctuation (here: !!!) due to recursive application of all rules to all new subtokens after split. Keep in mind, however, that his rules relies on the assumption that the whitespace after a punctuation mark is always correctly present. For example, this rule would not be able split a token such as "one,two,three".

Another mistake this rule makes is to potentially "destroy" emoticons which are often composed of punctuation marks. For example, the emoticon )-: ends with a colon, so the rule will split the emoticon. One possible extension to the rule would be to only split the punctuation mark if preceded by a letter. However, the emoticon )o: is preceded by a letter. While this could be solved by making the Regular Expression more complex to handle more special cases, we propose a more general approach using exceptions later on.

Handling Periods¶

Periods are tricky for tokenization because they serve multiple functions in written text, which makes it challenging to determine their role in a given context. Depending on how they are used, periods can represent the end of a sentence, abbreviations, decimal points, ellipses, or even part of domain names and email addresses. Misinterpreting their purpose during tokenization can lead to errors in understanding the structure and meaning of the text. Here are the main reasons periods pose challenges with examples:

- Multiple Functions:

- Periods are most commonly used to mark the end of a sentence. However, not all periods signify sentence boundaries, which complicates splitting text into sentences. For example, in the sentence "Dr. Smith arrived.", the period in "Dr." is not the end of a sentence.)

- Periods appear in abbreviations like Dr., e.g., or U.S., where they don't signify the end of a sentence. Treating them as sentence boundaries can disrupt parsing. To give an example: "E.g., we should consider other factors."

- A series of three periods ("...") indicates an omission or trailing thought, which tokenizers may mistakenly split into separate tokens.

- Embedded in Words or Numbers:

- Decimal Points: Periods are used in numbers (e.g., 3.14, $10.99) where splitting them into separate tokens would corrupt the numerical value. For example, given the sentence "The value is 3.14.", tokenizing it as ["The", "value", "is", "3", ".", "14"] would be incorrect.

- Web Addresses and Email: Periods in URLs or email addresses (e.g., "www.example.com", "user@example.com") should not be split.

- Context Sensitivity: Determining the role of a period requires analyzing the surrounding text. For example, after a lowercase word or a number, a period may signify an abbreviation or decimal; in contrast, after an uppercase word or sentence structure, it is more likely to indicate the end of a sentence.

In short, if a token ends with a period, we only want the period off if the token is not an abbreviation. We validate this by check if the sequence of characters before the final character and other period character — with the additional refinement that between the final period and any other period before, the must be at least one letter, digit, or parenthesis/bracket (e.g., we do not the last period in split "done..."). The test of not having a period character elsewhere is done by the negative lookbehind assertion (?<![.]). The method split_period_punctuation() with the complete Regular Expression checking the condition is:

def split_period_punctuation(token):

subtokens = []

# Abbreviations vs. sentence period (only split if not an abbreviation)

for match in re.finditer(r"(?<![.])([a-zA-Z0-9)\]}])([.]{1})$", token, flags=re.IGNORECASE):

subtokens.append(token[:match.span(2)[0]])

subtokens.append(token[match.span(2)[0]:])

return True, subtokens

return False, []

We can again run our tokenizer with this new rule added:

rules = [split_basic_punctuation,

split_period_punctuation

]

print(my_tokenizer.tokenize(text1, rules=rules))

print(my_tokenizer.tokenize(text2, rules=rules))

print(my_tokenizer.tokenize(text3, rules=rules))

print(my_tokenizer.tokenize(text4, rules=rules))

print(my_tokenizer.tokenize(text5, rules=rules))

["Let's", 'go', 'to', 'N.Y.', 'to', 'visit', 'my', 'mother-in-law', '!', '!', '!', "It'll", 'be', 'great', ',', "I'm", 'sure', '.'] ["I've", 'got', 'an', 'appointment', 'with', 'Dr', '.', 'Smith...I', 'hope', 'it', "won't", 'be', 'bad', '.'] ['Please', 'select', 'your', 'answer', ':', 'A', '(luggage)', 'or', 'B', '(no', 'luggage)', '.'] ['My', 'website', 'is', 'www.example.com', '(email', ':', 'user@example.com)', '#contact', '.'] ['The', 'ambience', 'was', ':o)))', ',', 'but', 'the', 'food', 'was', ')-', ':']

Most cases look good. All periods that mark the end of a sentence have been correctly tokenized, and the abbreviation N.Y. has been correctly preserved. However, our tokenizer is now too eager and has split the token Dr. The problem is that this is an example of an abbreviation that only has a single period at the end. This means, at least syntactically, there is no foolproof way to tell if this period marks the end of a sentence or abbreviation. One approach to solve this would be using probabilistic methods to decide which use is more likely given the context (i.e., the whole sentence). To avoid training models to predict the most likely use, we favor a simpler approach using exceptions; see later down below.

Clitics¶

Clitics are linguistic elements that function like words but lack independent phonological stress and must attach to a host word for proper pronunciation and meaning. They typically serve grammatical purposes, such as marking possession, negation, or contractions. Clitics are often pronounced as part of the host word, making them distinct from fully independent words.

Clitics play an essential role in simplifying speech and enhancing fluency. They allow for more efficient and natural communication by reducing the effort needed to articulate frequently used phrases or expressions. For instance, contractions like "I'm" for "I am" or "can't" for "cannot" make spoken language smoother and less formal. Clitics also help express grammatical relationships, such as possession in "John's book" or tense and agreement in contractions like "he's" ("he is" or "he has"). Common Clitics in English are:

- Contractions:

- 'm: "I'm" ("I am")

- 's: "he's", "she's" ("he is", "she is"); "it's" ("it is"); "John's" ("John has"/ possessive)

- 're: "you're" ("you are"), "they're" ("they are")

- 've: "I've" ("I have"), "we've" ("we have")

- 'll: "I'll" ("I will"), "she'll" ("she will")

- n't: "can't" ("cannot"), "won't" ("will not"), "doesn't" ("does not")

- Possessive Marker:

- 's: "John's book" (showing possession)

- ' (after plural nouns ending in "s"): "The dogs' toys" (showing possession for plural nouns).

- Reduced Forms: Common in informal speech, like "gonna" ("going to"), "wanna" ("want to"), or "lemme" ("let me"). Though not strictly clitics — and we can ignore those for our tokenizer — they function similarly in reducing effort in speech.

At least in English, the number of (common) clitics is very limited, making it very easy to enumerate them all and hard-code them as part of the rule. Then we can use a Regular Expression again to check if a token ends with any of the specified clitics. The method split_clitics() implements this new rule. Note that it considers only the most common clitics and English, but you can see how the code below could be tweaked to include more clitics.

def split_clitics(token):

# Define set of clitics

clitics = set(["n't", "'s", "'m", "'re", "'ve", "'d", "'ll"])

# Contains all the subtokens that might result from any splitting

subtokens = []

for match in re.finditer(rf"({'|'.join(clitics)})$", token, flags=re.IGNORECASE):

subtokens.append(token[:match.span()[0]])

subtokens.append(token[match.span()[0]:])

return True, subtokens

return False, []

Let's add the rule to the tokenizer to see if the results improve.

rules = [split_basic_punctuation,

split_period_punctuation,

split_clitics

]

print(my_tokenizer.tokenize(text1, rules=rules))

print(my_tokenizer.tokenize(text2, rules=rules))

print(my_tokenizer.tokenize(text3, rules=rules))

print(my_tokenizer.tokenize(text4, rules=rules))

print(my_tokenizer.tokenize(text5, rules=rules))

['Let', "'s", 'go', 'to', 'N.Y.', 'to', 'visit', 'my', 'mother-in-law', '!', '!', '!', 'It', "'ll", 'be', 'great', ',', 'I', "'m", 'sure', '.'] ['I', "'ve", 'got', 'an', 'appointment', 'with', 'Dr', '.', 'Smith...I', 'hope', 'it', 'wo', "n't", 'be', 'bad', '.'] ['Please', 'select', 'your', 'answer', ':', 'A', '(luggage)', 'or', 'B', '(no', 'luggage)', '.'] ['My', 'website', 'is', 'www.example.com', '(email', ':', 'user@example.com)', '#contact', '.'] ['The', 'ambience', 'was', ':o)))', ',', 'but', 'the', 'food', 'was', ')-', ':']

All clitics are now their own separate tokens. In general, this rule is unlikely to result in incorrect splits as this rule is very specific.

Hyphenated Words¶

Hyphenated words are compound words or phrases connected by a hyphen (e.g., "well-known", "mother-in-law", "self-esteem"). They are used to improve clarity, connect related ideas, or create new terms. Common rules for using hyphens in English are:

Compound adjectives before a noun: Compound adjectives are hyphenated when they come before the noun they modify (e.g., " a well-written article", "a high-quality product"). However, the compound adjective is not hyphenated when it comes after (e.g., "The article is well written.")

Numbers and fractions: Number from "twenty-one" to "ninety-nine" are hyphenated; so are fractions used as adjectives (e.g., "a two-thirds majority"). However, fractions used are nouns are not hyphenated (e.g., "Two thirds of the team left.")

Prefixes and suffixes: Hyphens may avoid confusion and improve readability when a prefix is added to a root word, including before proper nouns (e.g., "anti-American"), to avoid repeated vowels (e.g., "re-enter", "co-operate"), or to avoid repeated consonants (e.g., "shell-like"). Some common prefixes may or may not be hyphenated depending on usage (e.g., "nonessential" vs. "non-existent").

Compound nouns: Some compound nouns are hyphenated (e.g., "mother-in-law", "editor-in-chief"). Over time, many compound nouns evolve from hyphenated to single words (e.g., "email was" once written as "e-mail").

Clarity: Hyphen can be necessary to clarify meaning or prevent misreading (e.g., "small-business owners" vs. "small business owners"; or "re-cover the sofa" vs. "recover from illness").

Word breaks: When a word is too long to fit at the end of a line, a hyphen can be used to divide it, e.g., "Elephants are large land mam- mals found in Africa and Asia." (assuming there is a line break between "mam-" and "mels").

As a very general rule, the overuse of hyphens should be avoided. Only use hyphens when necessary; modern English increasingly moves toward closed compounds (e.g., "email" instead of "e-mail") or open compounds ("ice cream" instead of "ice-cream"). Still, hyphenated words are very common.

Hyphenated words are commonly tokenized for NLP tasks because they occupy a middle ground between single words and multi-word phrases, requiring careful handling to preserve meaning. Whether hyphenated words should be split during tokenization depends on the specific task and the desired level of granularity. In many cases, hyphenated words represent a single semantic unit, such as "mother-in-law" or "well-being", where splitting them could lead to a loss of meaning. For tasks like sentiment analysis, machine translation, or named entity recognition, preserving the entire hyphenated term as one token is often preferable, as the hyphen serves to unify the components into a concept that may not be accurately reconstructed from its parts. However, in tasks like linguistic analysis or when using subword-level models, splitting hyphenated words can be beneficial. Subword tokenization techniques often break words into smaller units to handle out-of-vocabulary (OOV) terms or morphological variations effectively. For instance, "state-of-the-art" might be split into subwords like "state", "-", "of", "-", and "art". This approach ensures that the model can process unseen or rare hyphenated words by understanding their constituent parts, while still preserving the structural information provided by the hyphen.

Ultimately, the decision to split or preserve hyphenated words depends on the balance between capturing semantic meaning and enabling flexibility for OOV words. For applications where the meaning of the hyphenated term is critical, keeping it intact is ideal. Conversely, different existing tokenizers may or may not tokenize hyphenated words. For our tokenizer to align with the basic spaCy tokenizer, we split hyphenated words. However, we only split with respect to a hyphen if it is preceded by a letter. This allows us to avoid splitting phone numbers (e.g., "555-1234") or dates ("10-10-2020"). We could also check if a hyphen is followed by a letter, but this might cause problem with word breaks (e.g., see the "mam-" examples above).

def split_hyphenated_words(token):

subtokens = []

for match in re.finditer(r"([a-zA-Z]+)(-)", token):

subtokens.append(token[:match.span(2)[0]])

subtokens.append(token[match.span(2)[0]:match.span(2)[1]])

subtokens.append(token[match.span(2)[1]:])

return True, subtokens

return False, []

Let's run the tokenizer over our example sentences with this rule added to the rule set.

rules = [split_basic_punctuation,

split_period_punctuation,

split_clitics,

split_hyphenated_words]

print(my_tokenizer.tokenize(text1, rules=rules))

print(my_tokenizer.tokenize(text2, rules=rules))

print(my_tokenizer.tokenize(text3, rules=rules))

print(my_tokenizer.tokenize(text4, rules=rules))

print(my_tokenizer.tokenize(text5, rules=rules))

['Let', "'s", 'go', 'to', 'N.Y.', 'to', 'visit', 'my', 'mother', '-', 'in', '-', 'law', '!', '!', '!', 'It', "'ll", 'be', 'great', ',', 'I', "'m", 'sure', '.'] ['I', "'ve", 'got', 'an', 'appointment', 'with', 'Dr', '.', 'Smith...I', 'hope', 'it', 'wo', "n't", 'be', 'bad', '.'] ['Please', 'select', 'your', 'answer', ':', 'A', '(luggage)', 'or', 'B', '(no', 'luggage)', '.'] ['My', 'website', 'is', 'www.example.com', '(email', ':', 'user@example.com)', '#contact', '.'] ['The', 'ambience', 'was', ':o)))', ',', 'but', 'the', 'food', 'was', ')-', ':']

Now "mother-in-law" has been split into all its components. However, appreciate that this is done by applying the rule twice, first splitting "mother-in-law" into "mother", "-", and "in-law", and later splitting "in-law" into "in", "-", and "law" through the recursive application rules to any new subtoken.

Again, splitting hyphenated words is not an obvious decision, and not all tokenizer will perform this split. However, the default tokenizer spaCy does split hyphenated words, and so we add this rule to our tokenizer. However, we only split if a hyphen is between two letters. For example, our rule does not split "5-3", but the spaCy tokenizer would split such a token. Which approach is the preferred is arguably not obvious.

Ellipsis¶

An ellipsis ("...") consists of three evenly spaced periods is a versatile bit of punctuation, typically used in fiction to show hesitation, omission or a pause, and in non-fiction to show a direct quote has been altered. Depending on which style guide, an ellipsis can be written with or without spaces before, after or between the dots. An ellipsis commonly used to indicate:

Omission: An ellipsis is used to indicate that something has been left out, often in a quotation or excerpt. For example, if the original sentence is "I think that this is the most important decision we will ever make.", using an ellipsis, it can be shortened to "I think that this is...important."

Pause or hesitation: An ellipsis can show a pause in speech or thought, often to create suspense or to reflect uncertainty, for example, "I was thinking...maybe we should try something else."

Trailing off: An ellipsis can suggest that a sentence is incomplete or that the speaker is leaving something unsaid, for example, "Well, I guess that's just how things are..."

In general, an ellipsis should be treated as a three-letter word, with a space, three periods and a space. However, since it is often omitted (particularly in social media content) we need a special rule for ellipses. This includes that the ellipsis might have more than just three dots. While we could incorporate the check for an ellipsis in the rules to check the usage of period marks, it would make these rules unnecessarily complex; it is cleaner to handle this using a separate rule.

Checking if a token contains a sequence of three or more periods is very easy, and we can again do this using a Regular Expression; the method split_ellipses() implements the new rule. Notice that the method will only split with respect to the first occurrence of an ellipsis in a token, even if there are multiple occurrences. However, this is not a problem due the recursive checking of all new subtokens.

def split_ellipses(token):

components = []

for match in re.finditer(r"[.]{3,}", token):

components.append(token[:match.span()[0]])

components.append(token[match.span()[0]:match.span()[1]])

components.append(token[match.span()[1]:])

return True, components

return False, []

Adding this new rule, our tokenizer should now correctly tokenize each ellipsis.

rules = [split_basic_punctuation,

split_period_punctuation,

split_clitics,

split_hyphenated_words,

split_ellipses]

print(my_tokenizer.tokenize(text1, rules=rules))

print(my_tokenizer.tokenize(text2, rules=rules))

print(my_tokenizer.tokenize(text3, rules=rules))

print(my_tokenizer.tokenize(text4, rules=rules))

print(my_tokenizer.tokenize(text5, rules=rules))

['Let', "'s", 'go', 'to', 'N.Y.', 'to', 'visit', 'my', 'mother', '-', 'in', '-', 'law', '!', '!', '!', 'It', "'ll", 'be', 'great', ',', 'I', "'m", 'sure', '.'] ['I', "'ve", 'got', 'an', 'appointment', 'with', 'Dr', '.', 'Smith', '...', 'I', 'hope', 'it', 'wo', "n't", 'be', 'bad', '.'] ['Please', 'select', 'your', 'answer', ':', 'A', '(luggage)', 'or', 'B', '(no', 'luggage)', '.'] ['My', 'website', 'is', 'www.example.com', '(email', ':', 'user@example.com)', '#contact', '.'] ['The', 'ambience', 'was', ':o)))', ',', 'but', 'the', 'food', 'was', ')-', ':']

Again, this is a rather "safe" rule that is unlikely to result in any "overzealous" tokenization as the rule is also very specific.

Parentheses & Quotes¶

Content within parentheses in a sentence or text serves various purposes, primarily to provide additional information, clarify meaning, or introduce asides. Parenthetical content is often non-essential to the main point but adds value to the reader's understanding. The most common use cases are:

Additional information or explanation: Parentheses can include extra details that enhance understanding without interrupting the flow of the main sentence, e.g.: "She loves Italian food (especially pasta and pizza)." (adds specific examples without making the sentence cumbersome).

Clarifications: Parentheses can clarify ambiguous terms, phrases, or references, e.g., "He moved to Washington (the state, not D.C.)." (avoids confusion by distinguishing between similar terms).

Citations or references: Parentheses are commonly used to provide references, citations, or source information in academic or formal writing, e.g., "The study was published in 2020 (Smith et al., 2020)." (attributes information without interrupting the narrative flow).

Abbreviations or acronyms: Parentheses are used to introduce acronyms or abbreviations after the full term, e.g., "The World Health Organization (WHO) monitors global health trends." (defines an acronym for later use in the text).

Asides or side comments: Parentheses can enclose asides, comments, or additional thoughts that are less formal or tangential to the main point, e.g., "We decided to stay at the beach longer (it was such a beautiful day)." (adds a personal or conversational tone).

Indicating choices or alternatives: Parentheses can present optional words or phrases, e.g., "The applicant must bring a valid ID (passport or driver’s license)." (specifies available options).

Editorial or authorial notes: In edited or quoted text, parentheses are used to insert editorial comments or explanations, e.g., "She stated, 'He left without explanation (which was unusual for him).'" (provides the editor's or author's clarification).

Content within quotation marks in a sentence or text serves several distinct purposes, primarily to indicate that the enclosed material is a specific kind of language or thought. Here are the primary purposes of using content in quotes:

Direct speech or dialogue: Quotation marks are used to enclose words spoken or written by someone, e.g., "She said, "I will meet you at 5 PM."" (accurately conveys someone's spoken or written words, distinguishing them from the narrator's text).

Quoting or citing Sources: Quotation marks indicate text taken directly from another source, ensuring proper attribution, e.g., "The article stated, "Climate change is accelerating at an unprecedented rate."" (allows the writer to incorporate someone else's words exactly as they were written or spoken, providing credibility or context).

Emphasis or irony: Quotation marks can highlight a word or phrase to show that it's being used in a special, ironic, or non-standard sense, e.g., "The so-called "expert" couldn't answer a simple question." (signals that the term is being used ironically, skeptically, or unconventionally).

Titles of short works: In English, quotation marks are used to denote titles of short works like articles, poems, short stories, songs, or chapters in books, e.g., "I loved the poem "The Road Not Taken" by Robert Frost." (differentiates shorter works from longer ones, which are italicized or underlined).

Words as words (metalinguistic use): When a word or phrase is mentioned as the word itself (rather than its meaning), quotation marks are often used, e.g., "The word "affect" is often confused with "effect."" (highlights the word as an object of discussion).

Signaling slang, jargon, or unfamiliar terms: Quotation marks can indicate unfamiliar, foreign, or technical terms, especially upon first use, e.g., "The term "schadenfreude" means taking pleasure in someone else's misfortune." (signals to the reader that the term may be new or require explanation).

Highlighting ambiguity or disputed terms: Quotation marks can indicate terms that are contentious or uncertain. e.g., "The policy was described as "progressive" by its proponents." (signals that the term may not be universally accepted or has a specific connotation).

The convention of using parenthesis/quotes in writing is that there is no whitespace between parentheses/quotes and inner content, but there are whitespaces between parentheses/quotes and surrounding text (except when directly adjacent to punctuation). For our rule, we therefore identify any parentheses and quotes at the beginning or end of a token and split it off if present. To make the rule a bit more flexible, apart from parentheses (( and )), the rule also looks for square brackets ([ and ]) and curly brackets ({ and }). In case of quotes, we limit ourselves to double quotes (") to keep things simple. The method split_parentheses_quotes implements this combined rule.

def split_parentheses_quotes(token):

components = []

for match in re.finditer(r"[(){}\[\]\"]{1}", token):

components.append(token[:match.span()[0]])

components.append(token[match.span()[0]:match.span()[1]])

components.append(token[match.span()[1]:])

return True, components

return False, []

As usual, we can test the rule by adding it to our rule set and run our tokenizer over the example sentences.

rules = [split_basic_punctuation,

split_period_punctuation,

split_clitics,

split_hyphenated_words,

split_ellipses,

split_parentheses_quotes

]

print(my_tokenizer.tokenize(text1, rules=rules))

print(my_tokenizer.tokenize(text2, rules=rules))

print(my_tokenizer.tokenize(text3, rules=rules))

print(my_tokenizer.tokenize(text4, rules=rules))

print(my_tokenizer.tokenize(text5, rules=rules))

['Let', "'s", 'go', 'to', 'N.Y.', 'to', 'visit', 'my', 'mother', '-', 'in', '-', 'law', '!', '!', '!', 'It', "'ll", 'be', 'great', ',', 'I', "'m", 'sure', '.']

['I', "'ve", 'got', 'an', 'appointment', 'with', 'Dr', '.', 'Smith', '...', 'I', 'hope', 'it', 'wo', "n't", 'be', 'bad', '.']

['Please', 'select', 'your', 'answer', ':', 'A', '(', 'luggage', ')', 'or', 'B', '(', 'no', 'luggage', ')', '.']

['My', 'website', 'is', 'www.example.com', '(', 'email', ':', 'user@example.com', ')', '#contact', '.']

['The', 'ambience', 'was', ':o', ')', ')', ')', ',', 'but', 'the', 'food', 'was', ')', '-', ':']

If a token has a parenthesis or bracket character both and the begging and at the end — that is the content in the parentheses/brackets is a single word — the rule first splits of the first occurrence and then the second occurrence due to the recursive application of all rules to all new subtokens. The example sentences also include emoticons that use a parenthesis character as a "mouth", either at the beginning or the end of the emoticon. Like with the use of punctuation marks as part of emoticons, we will try to improve on that using exceptions.

Exceptions¶

After implementing a testing series of splitting rules, we already noticed some cases where a token was split when it should not be. The first case relates to abbreviations that contain only a single period at the end, making them (syntactically) indistinguishable from periods marking the end of a sentence (which we want to split off). Secondly, the rules looking for punctuation marks and parentheses/brackets are likely to incorrectly split emoticons, as they often are composed of such characters. While emoticons are not common in more formal content such as news articles, they are very common in user-generated, and thus more informal content. For example, correctly tokenizing emoticons can be very useful when building a sentiment classifier, as emoticons are often used to convey or emphasize a sentiment.

To address such issues, one approach is trying to revise and improve the existing rules. However, this may add some significant complexity to the conditions of a rule, in turn might cause new issues during tokenizing. Particularly when multiple rules may cause the same problem — for example, splitting punctuation marks and parentheses/brackets can break up emoticons — fixing the same effect requires revising multiple rules.

Instead, we introduce the ideas of an exception. In general, an exception is a condition to check if a token should be preserved as is (i.e., not split). If such a condition evaluates to True for a token, no splitting rules are applied and the token is not split. Each exception is implemented as a method which takes a token as input and returns True (exception; preserve the token) or False (no exception; go ahead and apply splitting rules). The pseudo code below shows the basic structure of a method implementing a splitting rule.

def is_exception(token):

if <exception_condition> == True:

return True

else:

return False

Let's create two exceptions to handle the two cases where our tokenizer currently fails.

(Special) Abbreviations¶

Our splitting rule split_period_punctuation() can already handle abbreviations that contain more than one period (e.g., "N.Y.", "U.S.A."). However, an abbreviation with a single period at the end is indistinguishable from an end-of-sentence marker — at least when considering only the token itself without any context like the surrounding words. Advanced tokenizers might apply probabilistic methods such as training a classifier to predict if a period at the end of a token marks an abbreviation or the end of a sentence. However, this requires an annotated dataset for training and generally adds significant complexity to the tokenizer.

Instead, we utilize the fact that there are not that many common abbreviations with a single period in the end. This allows us to simply enumerate all abbreviations we want to consider and check if a token is in this predefined set. In fact, the spaCy tokenizer implements a very similar look-up to handle such exceptions; you can check out the relevant source code here). Implementing this exception is very straightforward. The method is_abbreviation() simply defines the fixed set of abbreviations and then checks if the input token matches any of those abbreviations. The implementation of the code cell below only list a good handful of abbreviations as examples, but it's obvious how this code could be extended to cover more abbreviations.

def is_abbreviation(token):

known_abbreviations = set(["mr.", "ms.", "mrs.", "prof.", "dr.", "mt.", "st."])

if token.lower() in known_abbreviations:

return True

return False

Now let's tokenize our five example sentences with that exception. Note that rules is expected to be the list of all the splitting rules we have implemented before.

exceptions = [is_abbreviation]

print(my_tokenizer.tokenize(text1, rules=rules, exceptions=exceptions))

print(my_tokenizer.tokenize(text2, rules=rules, exceptions=exceptions))

print(my_tokenizer.tokenize(text3, rules=rules, exceptions=exceptions))

print(my_tokenizer.tokenize(text4, rules=rules, exceptions=exceptions))

print(my_tokenizer.tokenize(text5, rules=rules, exceptions=exceptions))

['Let', "'s", 'go', 'to', 'N.Y.', 'to', 'visit', 'my', 'mother', '-', 'in', '-', 'law', '!', '!', '!', 'It', "'ll", 'be', 'great', ',', 'I', "'m", 'sure', '.']

['I', "'ve", 'got', 'an', 'appointment', 'with', 'Dr.', 'Smith', '...', 'I', 'hope', 'it', 'wo', "n't", 'be', 'bad', '.']

['Please', 'select', 'your', 'answer', ':', 'A', '(', 'luggage', ')', 'or', 'B', '(', 'no', 'luggage', ')', '.']

['My', 'website', 'is', 'www.example.com', '(', 'email', ':', 'user@example.com', ')', '#contact', '.']

['The', 'ambience', 'was', ':o', ')', ')', ')', ',', 'but', 'the', 'food', 'was', ')', '-', ':']

As expected, "Dr." is no longer split and represents its own token.

Emoticons¶

Emoticons are symbols created using keyboard characters, like letters, numbers, and punctuation marks, to represent emotions, facial expressions, or ideas. Unlike emoji (colorful pictures), text emoticons are simple combinations like ":)" for a smile, ":(" for sadness, or ":P" for playfulness. They were popular before emojis became common and are still used today, especially in places where emojis might not be available. The purpose of text emoticons is to make written communication more expressive. They help show emotions or tone in a way that plain text alone cannot. For example, if someone writes "I'm okay," it might seem neutral, but adding ":)" shows positivity, while ":(" indicates sadness. This helps readers understand the writer's mood and makes the message clearer and more personal. Emoticons also add a friendly and fun element to messages. They make conversations feel less formal and more engaging, especially in casual chats. By using a wink ";)" or a laughing face "XD", people can add humor or playfulness, making digital communication feel warmer and more relatable. There are two main types of emoticons

Western-style emoticons are text-based symbols that represent facial expressions and emotions. They are typically created using keyboard characters and are designed to be read horizontally, with the eyes, for example, usually represented by colons (

:), semicolons (;), or other symbols. Western-style emoticons are widely used in informal written communication like chats, emails, and social media. They are simple and easy to create with a standard keyboard, making them accessible across devices and platforms. Western-style emoticons focus on basic facial expressions and rely on the horizontal orientation for interpretation.Japanese-style emoticons, also known as kaomoji are text-based emoticons that express emotions and actions. They are typically read vertically, Kaomoji often use a variety of characters, including letters, punctuation marks, and special symbols, to create detailed and expressive faces. Example include Happiness:

(^‿^)or(⌒‿⌒)for happiness,(︶︹︺)or(T_T)for sadness,(*°▽°*)or(O_O)for surprise,(♥‿♥)or(。♥‿♥。)for love,(¬_¬)or(ಠ_ಠ)for anger, or(⁄⁄>⁄ω⁄<⁄⁄)or(〃ω〃)for shyness. Kaomoji are designed to be understood without tilting your head and often use many diverse characters to go beyond basic emotions to depict complex feelings. Kaomoji are especially popular in Japan but have gained international appeal due to their creativity and ability to convey nuanced emotions.

In principle, we could preserve emoticons using a set of predefined set emoticons (similar to the set of predefined abbreviations used in the previous exception). And in fact, for kaomoji we have to adopt this approach. The only little addition is to reflect the observation that the enclosing parentheses of kaomoji are often omitted.

Western-style emoticons are often simpler but typically also exhibit the same structure. A Western-style emoticons can typically be broken up in four components:

- Top (optional): a character representing a hat or furrowed brows.

- Eyes: a character representing the eyes of a face

- Nose (optional): a character representing the nose of a face

- Mouth: a character representing the mouth of a face

For example, the emoticon >:-| may express some doubt or skepticism using furrowed brows and a non-smiling mouth. Many emoticons are much simpler, having only eyes and mouths, e.g., ;) or :(. Each part of the face is commonly represented by a small set of characters. For example, eyes are mostly represented by :, ;, 8, =, and some other characters. Utilizing this structure of Western-style emoticons, we can actually write a Regular Expression to capture the most popular emoticons. This allows us to even capture slight variations. For example, it is very common that the mouth character is repeated (e.g., :o)))); the spaCy tokenizer will split off the two additional closing parentheses characters and only preserve the standard emoticon. The only additional consideration is that a Western-style emoticon can be written in both "directions", that is: top-eyes-nose-mouth or mouth-nose-eyes-top. We therefore need two Regular Expressions to account for both reading directions.

The method is_emoticon() implementing this exception is putting all those considerations together. Compared to is_abbreviation(), this method has a certain complexity which might not be needed in practice. However, it provides a good example for more application-specific implementations; again, reliably preserving emoticons can be very useful for sentiment analysis.

def is_emoticon(token):

# Western Emoticaons (both orientations)

TOPS = '[]}{()<>'

EYES = '.:;8BX='

NOSES = '-=~\'^o'

MOUTHS = ')(/\|DPp[]{}<>oO*'

# Generic patterns

p = re.compile("^([%s]?)([%s])([%s]?)([%s]+)$" % tuple(map(re.escape, [TOPS, EYES, NOSES, MOUTHS])))

for m in p.finditer(token):

return True

# Generic patterns (mirrored orientation)

p = re.compile("^([%s]+)([%s]?)([%s])([%s]?)$" % tuple(map(re.escape, [MOUTHS, NOSES, EYES, TOPS])))

for m in p.finditer(token):

return True

# Kaomoji (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kaomoji)

t = token

for match in re.finditer(r"(?<=[({\[])(.*)(?=[})\]])", t):

t = t[match.span()[0]:match.span()[1]]

known_emoticons = set(["^_^", "^^", "^-^"])

if t.lower() in known_emoticons:

return True

return False

Let's run our tokenizer with this additional exception.

exceptions = [is_abbreviation,

is_emoticon]

print(my_tokenizer.tokenize(text1, rules=rules, exceptions=exceptions))

print(my_tokenizer.tokenize(text2, rules=rules, exceptions=exceptions))

print(my_tokenizer.tokenize(text3, rules=rules, exceptions=exceptions))

print(my_tokenizer.tokenize(text4, rules=rules, exceptions=exceptions))

print(my_tokenizer.tokenize(text5, rules=rules, exceptions=exceptions))

['Let', "'s", 'go', 'to', 'N.Y.', 'to', 'visit', 'my', 'mother', '-', 'in', '-', 'law', '!', '!', '!', 'It', "'ll", 'be', 'great', ',', 'I', "'m", 'sure', '.']

['I', "'ve", 'got', 'an', 'appointment', 'with', 'Dr.', 'Smith', '...', 'I', 'hope', 'it', 'wo', "n't", 'be', 'bad', '.']

['Please', 'select', 'your', 'answer', ':', 'A', '(', 'luggage', ')', 'or', 'B', '(', 'no', 'luggage', ')', '.']

['My', 'website', 'is', 'www.example.com', '(', 'email', ':', 'user@example.com', ')', '#contact', '.']

['The', 'ambience', 'was', ':o)))', ',', 'but', 'the', 'food', 'was', ')-:']

While not perfect, the Regular Expression matching Western-style emoticons should capture a wide range of the most popular variations.

Discussion & Limitations¶

When looking at the results for all the example sentences so far, our tokenizer seems to do a decent job using the rules and exceptions we have implemented so far. However, the example sentences have been chosen to contain all aspects relevant to the rules and exceptions. It is rather easy to come up with sentences where the tokenizer will not behave as probably expected. Here are some simple examples:

text6 = "Tell her that she got an A- in her exam;her phone number is 555 1234-5"

text7 = "I've visited my mother—in—law yesterday."

print(my_tokenizer.tokenize(text4, rules=rules, exceptions=exceptions))

print(my_tokenizer.tokenize(text6, rules=rules, exceptions=exceptions))

print(my_tokenizer.tokenize(text7, rules=rules, exceptions=exceptions))

['My', 'website', 'is', 'www.example.com', '(', 'email', ':', 'user@example.com', ')', '#contact', '.']

['Tell', 'her', 'that', 'she', 'got', 'an', 'A', '-', 'in', 'her', 'exam;her', 'phone', 'number', 'is', '555', '1234-5']

['I', "'ve", 'visited', 'my', 'mother—in—law', 'yesterday', '.']

The limitations of our current tokenizer implementation include

Right now, our tokenizer does not split hashtags such as "#contact", but the spaCy tokenizer would break it up into "#" and "contact". Which one is the preferred solution might depend on the exact application use case. However, from the rules implemented so far, it should be straightforward to implement another rule that splits such hashtags or user handles (e.g., "@TomHanks") if needed.

The token "exam;her" was not split correctly since the writer omitted the required whitespace character after the semicolon. While we assumed that the input text adheres to common orthographic rules and conventions, real-world data might not always be that well-formed. In principle, this can be remedied by improving the rule to check if a punctuation mark (excluding a period) is directly preceded and followed by at least one letter.

The grade "A-" has been split as it was treated as an hyphenated word; whether this is the preferred tokenization is up for arguments. Recall that we explicitly did not check if a hyphen is followed by at least one letter to match word breaks. Again, one can easily come up with more complex rules and/or exceptions — require hyphens to be preceded and followed by a letter and handle word breaks separately (as word breaks are not some common anymore in online content)

Since the tokenizer breaks up strings based on whitespace characters, it will also split substrings that "belong together" but include a whitespace (e.g., the phone number in the example above). This can include compound nouns ("post office", "train station") and named entities (e.g., "New York City", "Tom Hanks"). While these words belong together semantically, most tokenizers work purely on a syntactic level and therefore cannot reliably identify if two or more words should form a single token. Thus, basically all word tokenizers do not support multi-word tokens.

An assumption we did not explicitly mention is that all input text contains standard ASCII characters. For example, for the rules handling hyphenated words and clitics, we only considered the hyphen

-and single quote'that are in the ASCII standard. However, there are now many text encoding standards that go way beyond the limited character set of ASCII. For example, instead of the normal hyphen, an em dash might be used (see exampletext7above).

In short, there are many cases that prevent the use of our current tokenizer in a real-world use case. While in many cases improving the tokenizer by adding new rules/exceptions or improving existing rules/exceptions is rather straightforward, this complexity would go beyond the educational purposes of our implementation here.

Summary¶

A word tokenizer is a fundamental component in natural language processing (NLP) that breaks down text into smaller units, typically words or tokens. These tokens are the basic building blocks used for further processing, such as text analysis, machine learning, or linguistic research. For instance, a sentence like "This is a test." might be tokenized into ["This", "is", "a", "test", "."]. The tokenizer must account for various language intricacies, such as punctuation, contractions, and different writing systems, making it an essential tool in NLP pipelines.

Writing your own simple word tokenizer can be an excellent learning exercise for several reasons. Firstly, it provides insight into the complexities of text processing, such as handling whitespace, punctuation, and edge cases like hyphenated words or abbreviations. This hands-on approach helps you appreciate the challenges involved in accurately segmenting text, especially in languages with no spaces between words (e.g., Chinese or Thai) or languages with rich morphology. Moreover, building your own tokenizer helps demystify black-box tools and algorithms. While modern libraries like spaCy or NLTK provide highly optimized tokenizers, creating one from scratch reveals the underlying logic and decision-making processes involved. You’ll learn to balance simplicity and accuracy, making trade-offs that reflect real-world considerations in software development. Finally, this exercise fosters a deeper understanding of language itself. As you account for linguistic nuances like contractions ("don't"), compound words ("state-of-the-art"), or domain-specific terms, you’ll gain practical experience with the quirks of natural language. This foundational knowledge is invaluable for tackling more advanced NLP tasks like parsing, named entity recognition, or building language models.